It is well known that prewar Chicago had no “Japan town.” Was it simply because the Japanese population before 1940 was too small? Or was there a specific reason that Chicago did not establish a center for Japanese immigrants?

Jesse F. Steiner spent seven years (1905-1912) as a teacher at North Japan College in Sendai.1 He was subsequently trained under Robert Park and lectured in sociology at the University of Chicago in 1915 and 1916.2 In his thesis, The Japanese Invasion: A Study in the Psychology of Interracial Contacts, Steiner wrote:

An individual alone is not the same as when he is in a crowd of like-minded persons. For the same reason a Japanese living alone in an American community will think and act quite differently from his countrymen massed in one section of a city or living in a country district where Japanese predominates.3

The sparse population of Japanese Chicagoans, who were living alone among non-Japanese, probably had very different mentalities from the Japanese people living in “Japan towns” on the west coast. A Japanese newspaper reporter in New York noticed that the cosmopolitan nature of Chicago, which is a hub for trains from the east and west, formed a unique culture peculiar to the city.4 Did this ‘Chicago spirit’ discourage the Japanese from forming a “Japan town”? The Japanese writer, Kazuo Ito called Japanese Chicagoans “weedy” immigrants, as if they had sprung out the ground.5 Don't weeds need their own communities too?

The lack of a “Japan town” did not mean that the Japanese in Chicago lived with no sense of community. Rather, they were more keenly aware of their acute need for community, more so than west coast Japanese, because of their isolation from mainstream society.

According to Jesse Steiner, “Even in such a cosmopolitan city as Chicago, where, because of the comparatively small number of Japanese, prejudice against them is at a minimum, the Japanese residents with the possible exception of the students are made to feel that they are not an integral part of the social life of the city. They are not welcomed in social functions of Americans who are their equals in income and business position.”6

The Japanese immigrants in America usually formed various groups for mutual aid, in order to resist and overcome anti-Japan sentiments upheld by the surrounding society.7 Those same sentiments were evident in Chicago. Before the 1893 World’s Colombian Exposition in Chicago, Japanese living in Chicago had already formed such mutual aid groups.

The longest lasting one, dating from the early 20th century, was comprised of Japanese Christians. Many Japanese in pre-war Chicago were Christian, a fact that had actually been revealed at the 1893 Colombian Exposition by the Reverend D.D. Murray, an American missionary stationed in Osaka. Reverend D.D. Murray was in Chicago for the purpose of Christian ministry work among the Japanese during the Fair.8 He found a surprisingly a large number of Japanese Christians already residing in the city and held regular religious services with them two or three times a week.9

On the other hand, when speaking of Japanese Christians, we might also question when Chicago was exposed to Buddhism. According to The Encyclopedia of Chicago, “Buddhism had a minimal presence in Chicago prior to WWII.” After “representatives of some Asian Buddhist traditions attended the World’s Parliament of Religions held in conjunction with the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893,” “a Jewish businessman C. T. Strauss became the first formal convert to Buddhism on American Soil.”10

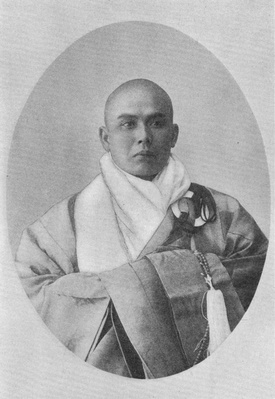

Six Japanese Buddhists, four monks, and two laymen, participated in the World’s Parliament of Religions and presented papers on Japanese Buddhism. A leader of the delegation, Shaku Soen, chief abbot of the prestigious Rinzai Zen complex Engakuji, acknowledged in his diary that Strauss’s conversion was “an achievement of the delegation” and an indication of the “success at Chicago in winning Western approval for Japanese Buddhism.”11

Furthermore, philosopher and first managing editor of the Open Court Publishing Company, Paul Carus, who was deeply influenced by his contacts with the Japanese delegation, was so moved that he wrote and published The Gospel of Buddha in 1894.

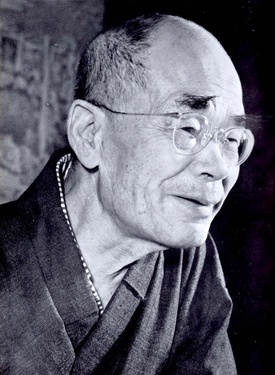

At the recommendation of Shaku Soen, the Japanese translator of this book, Daisetsu Teitaro (D.T.) Suzuki, came to La Salle, Illinois in 1897 to study under Carus’ guidance. Although his apprenticeship in La Salle continued for twelve years, from March 1897 to February 190912 and his work produced in La Salle was a “direct consequence of the delegation to Chicago,” Suzuki had to wait another half a century to see “his work lead the Zen boom of 1960s in America.”13

Despite the relative lack of interest in Buddhism in Chicago at the turn of the century, the Reverend Kentoku Hori, superintendent of the Japanese Buddhist mission, was sent to Chicago by the Honganji temple in San Francisco.14 He visited Chicago in September 1905 to establish a mission for the benefit of the Japanese community.15 However, it seems that Hori quickly gave up his missionary work in Chicago since his efforts were not successful. It wasn’t until October 1944 that the Reverend Gyomei Kubose, a Nisei born in San Francisco, established the first Buddhist temple in Chicago at 5487 Dorchester Avenue.16

Before Reverend Kubose’s temple was established, a young Zen priest named Reverend Soyu Matsuoka, who was sent from Sojiji temple in Yokohama to the U.S. for missionary work in June 1940, reached Chicago in August 1943. Since the U.S. was at war with Japan, he was arrested by the FBI later that same year. Before his detainment, he had contacted several prominent Japanese men in Chicago such as Masuto Kono and Charles Yamazaki, secretary-treasurer and president, respectively, of the Japanese Mutual Aid Society.

When Matsuoka asked “whether there is a need for a Buddhist church in this city” for Japanese residents, Kono responded that “many of the Japanese residents here belong to the Christian church and that it would be difficult for (Matsuoka) to establish a Buddhist temple and gather any followers because of the present war between Japan and the United States.”

Yamazaki also advised Matsuoka that “he himself was a Christian as were many of the Japanese residents here… and that he did not believe that (Matsuoka) would be successful in his mission.”17 Undeterred, Matsuoka finally opened a Zen temple at 2705 West Washington Boulevard in Chicago in November 1946.18 In short, building a Buddhist temple was not possible until the 1940s, after the Japanese and Japanese Americans were relocated to Chicago following their incarceration in the World War II concentration camps.

However, the first Japanese Christian church in Chicago had been established 30 years earlier, in May 1914. The church was never in need of preachers because Japanese Christian students were eager to study theology in Chicago, which was deemed “a world-class religious center with global influence.”19

Some of them returned to Japan after finishing their studies and became well-known priests there. Others stayed in the U.S. and chose to do missionary work, serving Japanese communities across the U.S. and Canada. One of those who stayed in Chicago was Misaki Shimazu. Through various activities at the church, Shimazu and his wife, Yone, along with many Japanese priests, worked hard to convert Japanese Chicagoans to Christianity, forming a Japanese Christian community in Chicago which grew to be an integral part of the wider Japanese community.

Notes:

1. The Japanese Student, August 1917.

2. Who's Who in Chicago, 1917.

3. Steiner, Jesse F. The Japanese Invasion: A Study in the Psychology of Inter-Racial Contacts, a dissertation, University of Chicago, page 111.

4. Nichibei Shuho, January 8, 1916.

5. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, page 268.

6. Steiner, page 109.

7. Sakaguchi, Mitsuhiro. “Nihonjin-imin to Shakai Jigyo,” The Journal of Shibusawa Studies, October 1993, page 17.

8. The Japan Weekly Mail, May 27, 1893.

9. The Japan Weekly Mail, July 8, 1893.

10. The Encyclopedia of Chicago, p.98.

11. Snodgrass, Judith, Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West, page 221.

12. Snodgrass, page 259.

13. Snodgrass, page 12.

14. Nichibei Shuho, December 13, 1902.

15. Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1905.

16. Chicago Tribune, October 9, 1944.

17. Matsuoka file 146-13-2-12-4370, FBI File No 100-13184 dated 10-4-43, NARA, College Park, Maryland, Reg 60, Box 201.

18. Fujii, Ryoichi, Shikago Nikkei-jin Shi, page 301.

19. Encyclopedia of Chicago, page 687.

© 2021 Takako Day