Prologue: The Power of Place

As archaeologists, we have experienced the power of place in all sorts of sites. But after almost 30 years investigating sites associated with the World War II mass incarceration of Japanese Americans, we have found these confinement sites among the most powerful, the most expressive. Bulky, immovable concrete foundations from guard towers and remnants of barbed wire speak of imprisonment. Communal latrines and mess halls tell of the lack of privacy and loss of family structure in confinement camps. Bakelite brooches speak of flag-waving American patriotism, while angry graffiti speaks of disillusionment and pain. Baby bottle fragments and toys, including marbles and small delicate doll fragments, disclose the ages of the smallest, most vulnerable prisoners.

All of the World War II Japanese American incarceration camps, from the large family centers that held thousands to the small gulags that held fewer than a dozen, are hallowed ground. All were scenes of an injustice perpetuated by a government against its citizens and residents. All are witnesses to a grave mistake, where ethnicity was persecuted, racism was sanctioned, and civil rights tossed aside. When the people who witnessed these events pass on, what holds the memories? Who decides which memories to keep? Archaeologists would say that the landscape can speak to us. The trees the prisoners planted tell us what to remember, the rocks they placed to decorate their barracks tell us who was there. They left traces of hope, faith, and love, as well as difficulties, despair, and death on the landscape.

Herein lies the tale of a monument, built, demolished, seemingly erased from the landscape, but in reality lying in wait to be discovered. Maybe those who were forced to destroy it meant for it to be found; perhaps they still had hope that a future America would want to hear their story.

1880–1942: An American Story

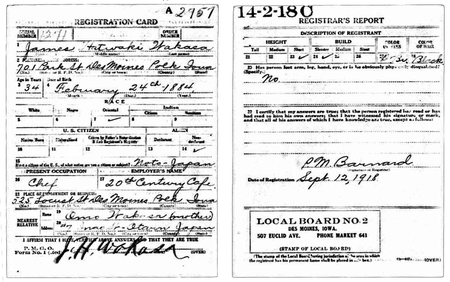

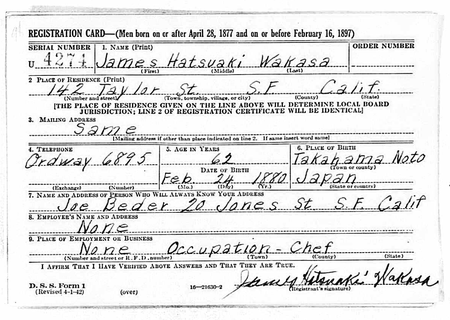

James Hatsuaki Wakasa was born in Takahama, Ishikawa, Japan, on February 24, 1880. He came to the United States as a young man in 1903. He was well-educated for that time: he had graduated from Keio College in Tokyo. When he immigrated, he studied at Hyde Park High School in Chicago for three years and completed a two-year post graduate course at the University of Wisconsin in 1916 (Topaz Times, April 12, 1943). Mr. Wakasa could read, speak, and write in both Japanese and English. He had registered for the draft in 1918, when he lived in Des Moines, Iowa, where he was a chef.

During World War I he was a civilian cooking instructor at Camp Dodge, Iowa, a regional training center for the U.S. military. For his World War I service he received American citizenship, but it was rescinded after the 1922 Ozawa Supreme Court decision.1

The 1940 U.S. census places Wakasa at Chicago, Illinois, in 1935. He had lived there for 14 years, and also spent time in St. Louis, Detroit, and New York before moving to California.2 In 1940 the census shows him living in Los Angeles, where, near 60 years of age, he was the oldest lodger in a boarding house with seven other men. The job market does not appear to have been particularly good for chefs at that time: he was out of work for 13 weeks in 1939, and 21 weeks in 1940. When he registered for the draft in April 1942, he was unemployed and living in San Francisco.

1942: In the Utah Desert

Although Mr. Wakasa was a well-traveled man, he was not in the Utah desert by choice. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forced removal and mass incarceration of all Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Some 120,000 civilians were incarcerated, most of them U.S. citizens. The majority of the others were immigrants who had lived in the country for decades but who had been denied citizenship because of racist laws. Their only “crime” was sharing ethnicity with a military enemy, the Empire of Japan. Those incarcerated included men, women, and children, even orphans and U.S. military veterans. They lost billions of dollars’ worth of homes, farms, and businesses; the social and psychological losses are incalculable. During World War II the “Relocation,” as it was euphemistically called, was justified as a military necessity.

By the time Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, the U.S. government had already determined that the Japanese American population did not pose a military threat. However, many newspaper editors, politicians, and members of the public did not distinguish between the Empire of Japan and the Japanese American farmers, fishermen, gardeners, teachers, doctors, merchants, students, and chefs who lived in the United States.

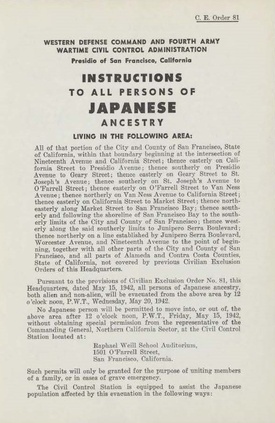

Mr. Wakasa’s San Francisco residence fell within Civilian Exclusion Area 81, which was “evacuated” May 20, 1942. He and his neighbors were sent to Tanforan Assembly Center, which had opened April 28, 1942. There, they awaited transfer to one of ten more-permanent incarceration centers.

Quickly constructed by the federal government in remote parts of the country, the “Relocation Centers” were expected to be self-sufficient, complete communities surrounded by guard towers and fences.

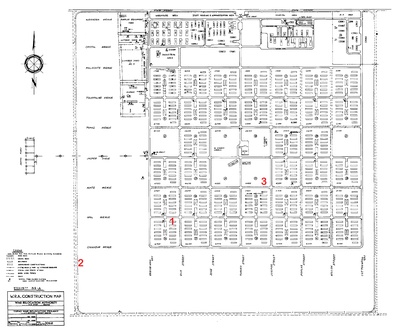

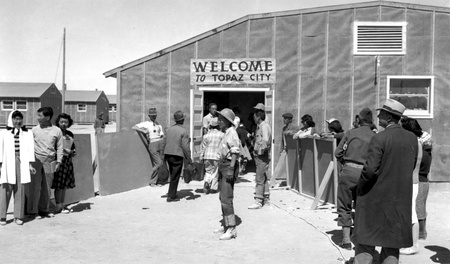

The Topaz or Central Utah Relocation Center was located in the flat terrain of west-central Utah, near the town of Delta. The relocation center was in operation from September 11, 1942, to October 31, 1945. The maximum population was 8,130; most of the internees were from the San Francisco Bay area. A total of 623 buildings were constructed during the life of the relocation center.3

The nucleus of the facility consisted of a one-square-mile area for residents, administrative personnel, and the military police. This “central area” included 36 blocks for prisoner residences and six undeveloped blocks. Each residential block had 12 barracks, a mess hall, a recreation hall, and a combination washroom, shower, toilet, and laundry building. After Topaz opened, sports fields, a gymnasium, and other facilities were built in the undeveloped blocks.

The administrative buildings were to the north of the residential blocks and included warehouses, staff housing, admission and clearance offices, the main gate, a post office, a fire station, a hospital, the military police compound, and later a tofu factory. Security features included a sentry post at the main gate, a perimeter fence, and seven guard towers (numbered 4 through 10).

Mr. Wakasa arrived at Topaz October 1, 1942, along with 500 others, while the camp was still under construction. He was assigned a space in Apartment D of Barracks 7 in Block 36. Like the other incarcerees, Mr. Wakasa tried to make the best of life in confinement. But in a little over 6 months, he would be dead.

Notes:

1. Sandra C. Taylor Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz. University of California Press, Berkeley. 1993:137.

2. Nancy Ukai, The Demolished Monument: James Hatsuaki Wakasa and the Erasure of Memory. 50 Objects/Stories: The American Japanese Incarceration. 1993.

3. Kent Powell, Topaz War Relocation Center National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form. Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City. 1972.

*Editor’s note: Discover Nikkei is an archive of stories representing different communities, voices, and perspectives. The following article does not represent the views of Discover Nikkei and the Japanese American National Museum. Discover Nikkei publishes these stories as a way to share different perspectives expressed within the community.

© 2020 Mary M. Farrell; Jeff Burton