Kato helped his father on the farm in central California, and when his father returned to Japan, he moved to Pasadena, near Los Angeles, to work in landscaping. However, he soon became a reporter for a Japanese newspaper, which marked the beginning of his long career in journalism.

Japanese language newspapers naturally emerged in immigrant communities in North America, Hawaii, and South America. This is because, with language barriers making it difficult to obtain information, information in Japanese is essential to life. Early Japanese language newspapers were political documents written by young people involved in the Freedom and People's Rights Movement in Japan, but as the number of immigrants increased, community newspapers in each region began to expand.

Japanese newspapers were established in Hawaii, San Francisco, Seattle, Los Angeles, as well as Denver, Salt Lake City, Chicago, etc. The Japanese newspaper in Los Angeles, where Kato Shinichi worked as a reporter, began as the Rafu Shimpo, which was launched in April 1903 (Meiji 36), much later than in San Francisco.

From Rafu Nichibei to California Mainichi

In the Taisho era, as the Japanese community developed and "Little Tokyo" was formed, newspapers such as "Rafu Nichibei" and "Southern California Times" were launched, followed by "California Mainichi" in 1931. These newspapers were constantly closed or merged due to management issues and differences in editorial policy, and there was a lot of staff turnover.

The "Rafu Nichibei" and "California Mainichi," for which Kato was a member, were no exception. In "Early Japanese-Language Newspapers in America" (edited by Tamura Norio and Shiramizu Shigehiko, Keiso Shobo), the events leading up to the closure of the former and the founding of the latter are described as follows, including Kato's name:

"Due to the effects of the recession in 1930, there were wage delays and other issues at the Nichibei Newspaper Company in Soko, and these discontents led to the Nichibei Newspaper strike in 1931. During this process, Rafu Nichibei, owned by president Abiko Hisataro, was sold and soon ceased publication. Inoue Isamu, Kato Shinichi, Matsui Toyozo and other employees of Rafu Nichibei who were sympathetic to the strike, went on to launch a new daily newspaper, California Mainichi, under Fujii Sei in November 1931."

Looking at this, we can see that Kato first worked as a reporter for Rafu Nichibei, and then became a reporter for California Mainichi to support the publisher.

Abiko Kyutaro (1865-1936) was a leader among Japanese immigrants and a businessman. He educated Japanese immigrants who had a strong desire to work abroad to settle in America and become part of the local community, and he also worked to make that happen.

From the digital archive of Japanese newspapers

What were Japanese newspapers like at the time? What kind of articles did Kato write? In the course of my research, I came across a website called "Japanese Newspaper Digital Collection: Japanese Diaspora Initiative."

This is housed in the Hoover Institution Library & Archives at Stanford University in the United States, and according to the explanation on the website,

"This is the world's largest online, open access, full-page image collection of overseas Japanese newspapers published by Japanese and Japanese-Americans living overseas in the Americas and Asia. Wherever possible, newspaper images are converted to text using optical character recognition (OCR) to make newspaper articles searchable. Each newspaper can be viewed by publication date, newspaper name, and place of publication, and cross-searches with other newspapers are possible on the site."

The site also digitizes Japanese newspapers published in the United States, and allows users to search for articles by keyword. When I searched for "Kato Shinichi" here, dozens of articles came up, including those written by him as a reporter and those written about him.

These articles are signed by Kato Shinichi and contain his name, and were published in the Rafu Shimpo, California Mainichi, Shinsekai Asahi Shimbun, Daihoku Nippo, and Nippu Jiji between 1925 and 1940.

Covering the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics

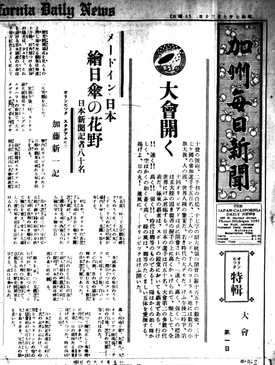

The search revealed articles written by Kato himself, including agricultural articles such as "Tometou Farmers: The Contents of the Unification Movement" (California Mainichi Shimbun, December 13, 1935) and articles making assertive statements like editorials, but the article that caught my eye the most was the "Olympics to be held in Los Angeles" article that appeared on the front page of the July 30, 1932 edition of the California Mainichi Shimbun.

In addition to the top story under the headline "The Grand Tournament Begins," the paper is filled with predictions of how Japanese athletes would perform in each sport under the headline "We'll win tomorrow! Watch Young Japan make their first appearance!" as well as interviews with individual athletes under the headline "Athletes share their aspirations before taking to the field."

The special edition on the Olympics includes two photographs of the stadium on the morning of the event, and the second article in the issue is titled "At the Olympic Stadium, by Kato Shinichi," under the headline "Made in Japan: Painted Parasols for 80 Japanese Newspaper Reporters."

Kato, who was at the stadium, wrote a vivid account of the opening of the Los Angeles Olympics on July 30th of that year. Below, we will introduce some of Kato's account of the opening, although it will be a bit long.

"Over 100,000 spectators flocked to see the historic opening ceremony, and although the Southern California sunlight was scorching hot, the Japanese-made parasols they used to protect themselves from the sun were a beautiful sight, with their colorful parasols offering a spectacular sight.

At 2:00 p.m. right on schedule, Vice President Curtis appeared at the main gate of the stadium wearing a morning coat and top hat, and the packed audience of over 100,000 people inside the stadium erupted in thunderous applause.

The Vice President took his seat in the Honorary President's seat, which was located on a raised platform at the front of the north side of the stadium, and at 2:35 p.m., as the entire audience stood, a large band of 2,000 people and a choir of 1,000 people filled the venue with energy as they performed the American Anthem.

As soon as it was over, the athletes from each country, in alphabetical order with the Greek representative at the front, filed out of the southwest entrance in a stately formation, each carrying their own placard and national flag.

At 3:03, the Japanese athletes, carrying the silk Hinomaru flag bestowed by Prince Chichibu at the front, lined up in the order previously reported, and made a dignified entrance to the stadium, where they were showered with thunderous applause. (The rest is omitted.)

Kato's enthusiasm for being entrusted with writing the article that would be the highlight of the day's paper was apparent.

(Titles omitted)

© 2021 Ryusuke Kawai