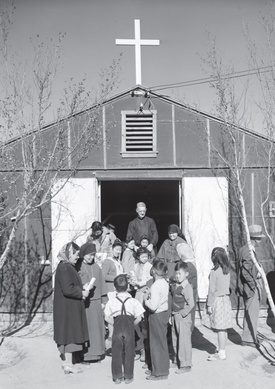

April 4, 2021 was Easter Sunday. While Easter celebrations in Little Tokyo do not hold the same importance as community festivities like Nisei Week, the celebration of Christian holidays (and even St. Patrick’s Day) at the St. Francis Xavier Chapel Japanese Catholic Center in Little Tokyo is a tradition that has gone on every year for decades.

Although the number of Catholics among Japanese Americans has always remained small – by government estimates, they only accounted for 2% of the total West Coast Japanese American population in 1940 – the Maryknoll Church of Little Tokyo and its clergy played a distinct role in shaping the Los Angeles community during that period.

So far, the best history written on Maryknoll’s long history in Little Tokyo is that by former Pacific Citizen editor, and former Maryknoller, Harry Honda. As Honda described it, the Maryknoll story begins in Little Tokyo in 1912.

That year, Leo Kumataro Hatakeyama, a veteran of the Russo-Japanese War, wrote to Bishop Alexandre Berlioz of Hakodate to confess his sins because, he explained, none of the priests in Los Angeles spoke Japanese. Bishop Berlioz told Hatakeyama that he was not permitted to confess via mail, and then decided to send one of his priests, Father Albert Breton, to Los Angeles to work with the Japanese community there.

After arriving in October 1912, Father Breton soon established a school and orphanage for the Japanese American community. Seven years later, Father Breton petitioned Maryknoll to assume responsibility for the Japanese American community.

Although the origins of Maryknoll’s presence in Los Angeles date from 1920, when the Vatican authorized them to assume control of the Japanese American mission in Little Tokyo, their real importance to the community dates from the arrival of Father Hugh Lavery in 1927. In the years before U.S. entry into World War II, Lavery directed the expansion of the Maryknoll School, overseeing the construction of an additional floor and the implementation of school bus service for Nisei students.

Outstanding Nisei alums of Maryknoll School include football star Bill Kajikawa, journalist and editor Larry Tajiri, and editor, archivist and historian for the Japanese-American community Harry Honda.

In 1924, Father Lavery arranged for the creation of one of the first Japanese American Boy Scout troops, Troop 145. The troop was led by Brother Theophane Walsh, who also drove the school bus (a benefit that allowed many students, like Joyce Okazaki, to attend school). Although Maryknoll School offered a regular American curriculum, its directors also encouraged Japanese language learning among the Nisei, and even engaged Issei teachers to offer Japanese language classes to students.

In 1930, Father Lavery helped the Maryknoll Sisters purchase what became the Maryknoll Sanitarium for tuberculosis in the Monrovia foothills. The sanitarium was one of the few institutions other than Hillcrest Sanitarium that welcomed Japanese American tuberculosis patients, and it continued to house a number of Japanese American patients through the war years.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, the Maryknoll mission remained as one of the few community centers in Little Tokyo that was not closed by authorities. Between December 1941 and March 1942, the Maryknoll auditorium became a regular meeting place for Nisei activists, like Rafu Shimpo English Editor Togo Tanaka, to discuss the future of the Nisei.

The Rafu Shimpo reported on numerous meetings held at the Maryknoll Auditorium, including a legendary meeting of the United Citizens Federation, chaired by Tanaka, that was held on Feb. 19, 1942, the day that Executive Order 9066 was issued, and where a variety of speakers campaigned against forced removal.

Meanwhile, the priests at Maryknoll worked overtime to assist the Japanese American community. In February 1942, Father Lavery visited the Fort Missoula Internment Camp in Montana to testify on behalf of Issei leaders held there. Following the eviction of Japanese Americans from Terminal Island, the Maryknoll Church provided space for uprooted families.

Father Lavery and Brother Theophane helped form a speaker’s bureau to mobilize public opinion behind Japanese Americans. Perhaps the most bitter moment came when Father Lavery asked WCCA (Wartime Civilian Control Administration) director Col. Karl Bendetsen about orphans of partial Japanese descent. Bendetsen replied that if any “have one drop of Japanese blood in them they must all go to camp.”

Once the Western Defense Command proceeded with mass incarceration of local Japanese Americans, the Maryknoll Brothers and Sisters helped organize families, and then joined them in camp.

By May 1942, all the Maryknoll clergy had left Los Angeles, and the Maryknoll school closed its doors. Throughout the incarceration period, Maryknoll priests and nuns worked in the ten War Relocation Authority concentration camps as spiritual leaders and teachers. Father Lavery wrote letters of support on behalf of Issei held by the FBI in internment camps, and travelled between the Manzanar and Tule Lake camps to celebrate mass.

One of Lavery’s sermons was featured by Carl Myden in March 1944 as part of his Life magazine report on the conditions inside of Tule Lake concentration camp. Maryknoll Sister Bernadette of Los Angeles maintained a school at Manzanar, and Brother Theophane organized a youth hostel in Chicago for Japanese Americans of all faiths leaving camp.

Following the end of exclusion in January 1945, Father Lavery and the Maryknoll clergy returned to Los Angeles along with Japanese American families, and the Maryknoll school reopened its doors. Maryknoll also restarted such time-honored traditions as the school band and the Boy Scouts. In 1957, Father Lavery left the Maryknoll Church for New Orleans, marking the end of his 30-year tenure in Los Angeles. In 1966, the Japanese government bestowed the Order of the Sacred Treasure upon Father Lavery for his tireless efforts to support the Japanese American community.

In the mid-1960s, the original Maryknoll school building was demolished, and a new building was constructed. Over the 1970s and 1980s, as Japanese Americans moved out of Los Angeles and into the suburbs, the Maryknoll School experienced a slow decline in enrollment.

In 1993, the Maryknoll Brothers transferred ownership of Maryknoll Los Angeles to the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, although the original title of “Maryknoll” was retained, in tribute to the order’s long history within Little Tokyo. After this transfer, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles closed the Maryknoll School and transformed it into the St. Francis Xavier Chapel Japanese Catholic Center.

The Maryknoll priests are now absent from Little Tokyo. Nonetheless, numerous Nisei and Sansei Maryknollers today attest to Maryknoll’s legacy and influence upon Little Tokyo.

Nisei Mary Suzuki Ichino later described Father Lavery as “very much a saint” for his work and activism.

For Sansei Patty Arra, Maryknoll School represented one of the last vestiges of the original Japanese American community: “Maryknoll School was one-of-a-kind with 99% of the students being Japanese American or Japanese. We celebrated our Japanese culture and Catholic faith within our community then and still do now with opportunities at Saint Francis Xavier Chapel Japanese Catholic Center. If you are a Japanese American/Japanese Catholic from Los Angeles, surely you must know Maryknoll.”

Author’s note: Special thanks to Patty Arra for her help with this article.

*This article was originally published in the Rafu Shimpo on April 1, 2021.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen