The second scene has to do with the final period of my studies in Japan. In a meeting with Okusama, the wife of Iemoto Sen Soshitsu XVI, the current Grand Master of the Urasenke School, my colleague Freddy from Taiwan asked what things we should keep in mind when returning home. She responded that we had learned our foundation there, that we should never forget it. And that, naturally, we would have to adapt some issues to the limitations that we could find in our countries of origin.

Grandmaster Sen Genshitsu . The Great Teacher says that the path of tea is a method by which we can accept our own luck and be satisfied with it.

“For example, the vast majority of people who practice tea today do not have access to a tea house or gardens that have been specially designed and built for tea gatherings. But whether or not a gathering takes place in such a setting, the host must direct his full attention to the needs and comfort of his guests; Your efforts should not be diminished simply because of a lack of the 'appropriate' qualities in the place in which to serve tea. Overcoming such insufficiency through creativity increases in direct proportion the depth of experience of both host and guest.” There will inevitably be an adaptation of the practice.

All this leads me to a question that always comes back: how to think about the future of tradition today? It is a question that encompasses the past, present and future. I am convinced that the role we tea practitioners have outside of Japan is important for the tea ceremony to continue to expand and, therefore, stay alive and moving.

The specific example that comes to mind is the popularity of matcha , the powdered green tea drunk in the tea ceremony, today. The consumption of matcha crossed the borders of Japan and today it can be bought anywhere. You can even drink it in large coffee chains mixed with sugar and milk, the product is called matcha latte . Matcha was also popularized (due to its flavor and green color) as an ingredient for pastries. Faced with this explosion of matcha fever, I am always interested in spreading the idea that it is a tea that is linked to history, philosophy and even politics in Japan. It is a drink that has enormous cultural weight and that means it is not simply a tea.

Chanoyu is the other name by which the practice of the ceremony is known and its translation is “hot water for tea”, meaning that originally it was only taken mixed with hot water without any other addition. The other word, Chad ō , completes the idea I was referring to before. “Cha” means tea, and “dō” means path. Chadō is passed throughout life and its deep learning permeates daily life. It is precisely what my grandmother called gyogi sahou. The path is daily life.

A green like tea, a green like mate

The writer Banana Yoshimoto visited Argentina many years ago and also passed through Brazil. In the essay “The Mystery of Mate” he tells something about that trip and in particular refers to Mr. Saito, a Japanese living in Brazil who, as Yoshimoto explains, had been living there for so long that he had become a South American. She also mentions that she drinks mate, and she tries it herself. Although he finds it strong, he begins to like it. “Perhaps a tea as powerful as that is necessary to continue living in that rigorous nature,” he reflects.

I like to think of this same postcard but in reverse: why do the Japanese drink matcha tea? And why did they devise and perfect the culture of the tea ceremony? Regarding the first question I have several possible answers. The custom of drinking matcha was brought from China by Zen monks, who drank it to sustain their long hours of meditation and as medicine. Around the year 1300, its consumption at ostentatious banquets became popular and it was in the 15th century with the Zen monk Murata Shuko that tea began to take on another meaning, which was finally established with the Grand Master Sen no Rikyu 2 in the 16th century. In parallel, the Japanese devised specific techniques for the cultivation of camellia sinensis , the tea plant, and to produce with it a matcha of excellence that no other country in the world could match.

Matcha is a strong tea, I dare say that it is even stronger than mate: due to its intensity, its color and its density. It is a rather thick liquid and when drinking it we are drinking the tea leaf directly, ground and mixed only with hot water.

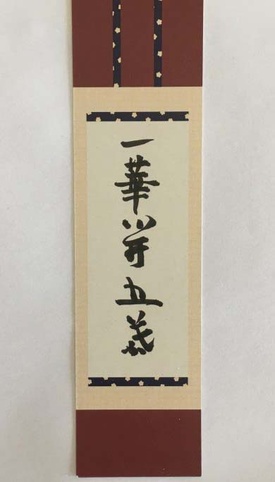

Regarding the second question, a tea meeting is, among many things, a communication through devices (a calligraphy, a flower arrangement, a meal called kaiseki , an incense ceremony) that communicate different things at very high levels of reading. deep, if you have enough knowledge. A tea meeting is a shared space and time, unique and unrepeatable. There is a very strong emotional closeness between the hostess and her guests but the physical distance and respect inherent to this ceremony (and Japanese culture in general) are maintained. It is a Japanese way of showing feelings. Many times they made the following comment to me: “So much trouble to prepare a cup of tea?” The cup of tea is the excuse. And everything else, each message behind each gesture, is what brings us together.

Keep learning

Another thing that I understood during my year of studies in Kyoto is that something that is highly valued in the world of tea is a capacity for inventiveness combined with good taste to choose the elements that will be used to prepare the tea. The Japanese are amused to see a mug made with non-Japanese designs and clays. Even the bamboo tea spoons are carved from local woods in places where bamboo does not grow, making a familiar item look and feel different in another material. The fun is being able to explain what type of wood it is, what tree it comes from; the same with ceramics. It is about being able to put together a story around these local crafts that will take on another dimension (and other meanings) now circulating in a tea room.

Organizing and planning a tea party necessarily forces us to deeply observe our environment, research the types of native ceramics, look for the names of the wildflowers that grow in local soil to make floral arrangements. This harmonious combination between objects from different parts of the world can lead to an interesting tea party.

In our weekly practices in Urasenke Argentina we used Japanese objects and little by little cups made here began to appear. In this mix, Japan is always present and begins to merge with each of the cultures where the tea ceremony is practiced. I think that Chadō is a way for my grandmother to always keep her connection with Japanese culture and her roots alive. Unconsciously I also turned towards that side and as I discovered that making tea was also a way to train the senses, to learn the deep meaning of calligraphy, prepare the sweets to serve and establish a dialogue with the flowers to be able to make a chabana (flower arrangement), I entered into a romance that continues to beat very strongly to this day.

When I ask my grandmother what she learned from all her teachers and from all these years of teaching, she says that she can't claim to know everything. “I'm still learning,” he responds with a smile. And with that answer disguised as simplicity, I return as in a spiral to the beginning of the essay: on this long journey of tea we always return to the starting point and learn to walk, over and over again.

Grades:

1. Feudal lord.

2. Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) elevated the tea ceremony to its highest expression: he ordered it, but also “Japanized” it through bamboo crafts and Japanese ceramic pieces, even giving rise to Raku ceramics. together with the ceramist Chojiro. It gave the tea ceremony an imprint linked to what is known as wabi aesthetics, a state of mind linked to frugality, simplicity and humility.

* This essay was originally published in the Nikkei Culture Dossier of Revista Transas (Universidad de San Martín) in October 2020. @revistatransas

© 2021 Malena Higashi