In the pre-World War II years, mainland Japanese Americans were all but absent from electoral office. Whereas in Hawaii there were Nisei representatives in the Territorial Assembly and even a Senator, Sanji Abe, those living elsewhere found endemic anti-Japanese prejudice an effective barrier to even running for elected office, though a few West Coast Nisei such as Clarence Arai and Karl Yoneda launched campaigns.

After World War II, a wave of Japanese American politicians rose to prominence as part of the changing dynamics of politics in the West. James Kanno was elected mayor of Fountain Valley in 1957, while in 1962 Seiji Horiuchi of Colorado became the first Japanese American elected to a state legislature.

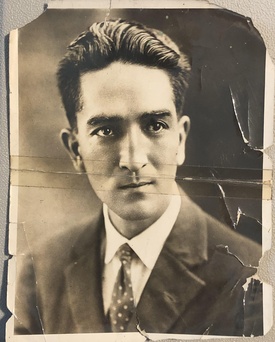

In 1966 Kiyoto Ken Nakaoka took a seat on Gardena’s city council. In 1971 Norman Mineta was elected mayor of San José and the late Eunice Sato was elected mayor of Long Beach, the first Nisei political leaders of large cities. Yet long before the postwar rise of Japanese American politicians, there was Kinjiro Matsudaira. Elected as mayor of the small Washington, D.C. suburb of Edmonston, Maryland in 1927, he was the first identifiably Asian elected official on the American continent. His political career forms part of a fascinating Matsudaira family saga, which is itself a part of the long history of mixed-race Japanese Americans.

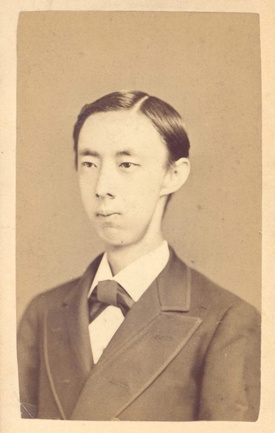

Kinjiro Matsudaira was born on September 13th, 1885 in Bradford, Pennsylvania. His father, Tadaatsu (AKA Tada Atsu) Matsudaira, the son of a Japanese noble family related to the Tokugawa Shoguns, was born in Edo (later known as Tokyo) in 1851. In 1872, Tadaatsu accompanied his brother Tadanari Matsudaira to the United States as part of the so-called Iwakura Mission, a diplomatic mission of statesmen and scholars sent by the newly founded Meiji government.

Once arrived, the two brothers enrolled at Rutgers University. Tadaatsu later transferred to Worcester Free Institute (later Worcester Polytechnic) and then to Harvard University, where he received a degree in civil engineering in 1877. It had been originally planned that the two brothers would return to Japan together following their studies. However, Tadaatsu Matsudaira fell in love with Carrie Sampson, the daughter of a local book and stationery store owner in New Brunswick, and he decided to stay in the United States rather than return to Japan. The couple were married following Tadaatsu’s graduation.

In the first years that followed, Tadaatsu worked for the Manhattan Elevated Railroad in New York. Within a few years, he took up railroad engineering with the Union Pacific Railroad in Wyoming, then worked at mines in Idaho and Montana. During this period, he invented the trigonometer, a surveying tool.

In 1884, he was hired as city engineer of Bradford, Pennsylvania. During these years, the Matsudairas had three children, of whom one died in infancy. Shortly after Kinjiro’s birth, Tadaatsu Matsudaira was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The Matsudaira family relocated to Denver, Colorado, in hopes that the dry western air would improve his health. There Tadaatsu worked for the Colorado State Engineer’s Office overseeing inspections on mining operations and worked as a surveyor. Afflicted by tuberculosis, Tadaatsu Matsudaira died in January 1888.

Kinjiro Matsudaira was only 3 years old when Tadaatsu died. Interestingly enough, he knew little about his Japanese family until 1925, when Tsuneo Matsudaira arrived in Washington as the new Japanese Ambassador, and Kinjiro wrote the American embassy in Tokyo to inquire whether he was from the same family. Although the embassy informed him that Tsuneo Matsudaira was not related to him, they informed him about his father’s family background.

Little documentation about Kinjiro’s childhood or education has survived. Following his father’s death, Kinjiro was sent to live with his maternal grandparents, William and Rachel Sampson, in Virginia. In the 1900 census the 14 year-old Kinjiro is listed as residing with his grandparents in Chesterfield County, Virginia, not attending school, and working as a farm laborer.

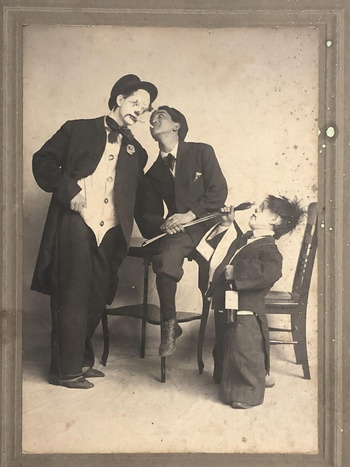

According to family legend, the Sampsons were either unwilling or unable to care for their “Japanese” grandson, and placed him in an orphanage they set up, and that he was so unhappy with his treatment there that he ran away from home and joined the circus. As fanciful as this tale may sound, a business card survives of “Kinjiro Matsudaria” listing him as manager of the Mataleamor trio, a group of three “Novelty Comic Acrobats” that included a “dwarf equilibrist.” Various photos reveal Matsudaira both in clown costume and out of makeup.

On September 19th, 1909, Kinjiro Matsudaira married Ellen Chisholm, a native of South Carolina (sometimes listed as Georgia) who was working as a store clerk at Goldenberg’s in Washington, D.C.. The wedding was officiated by Methodist minister Rev. R.L. Wright, and was announced in the Washington, D.C. newspaper The Evening Star. The wedding announcement characterized Kinjiro Matsudaira as employed by a business firm and as “a thorough American in all but name.” (Indeed, despite his Japanese name and ancestry, he would be listed as “white” on all his census returns between 1900 and 1940).

Matsudaira spent most of his life within the D.C. area. In the early years of their marriage, he and his wife Ellen lived with Ellen’s mother and stepfather in Washington DC. Later they lived in the suburban town of Hyattsville in Prince George’s County, Maryland. In the first decade of their marriage, Ellen and Kinjiro Matsdaira had three children, Haru Caroline, Ellen, and Robert Ford Matsudaira. Sometime before 1917, Matsudaira took a job as a clerk and bookkeeper at the Woodward and Lothrop department store in Washington. Matsudaira also worked as an inventor, following in the footsteps of his father. He received a patent in 1914 for a fire detector he invented.

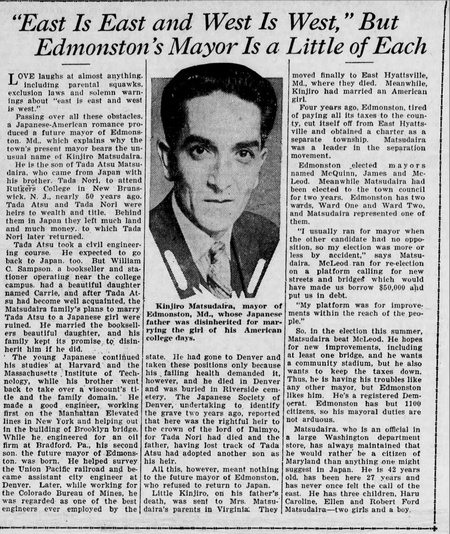

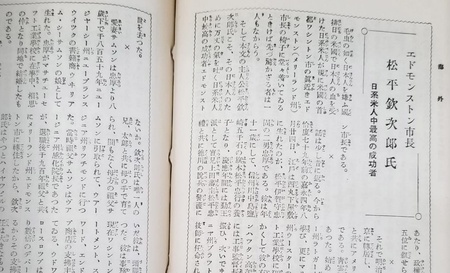

In 1924, Matsudaira helped spearhead a movement to separate the town of Edmonston from East Hyattsville, Maryland. The town was split between two wards, with Matsudaira becoming city councilman of Ward 2. In July 1926, Kinjiro formally announced his candidacy for mayor of Edmonston, running against fellow councilman D.H. McLeod of Ward 1. After running on a platform to improve the town’s infrastructure, Matsudaira beat McLeod, and was sworn into office in 1927. Matsudaira’s election as the first Japanese American mayor received significant attention from newspapers across the U.S. The New York Herald Tribune profiled him as the U.S.’s “first Japanese mayor,” and nationally syndicated articles featured discussion of Matsudaira and his family connections to Japanese rulers.

In the Japanese American press, Matsudaira’s election as mayor of Edmonston was well received. The San Francisco Nichi Bei Shinbun headlined its story “Japanese Born in U.S. to be Elected Mayor of Town in Maryland,” although few details were given beyond Matsudaira being no relation to Japanese Ambassador Tsuneo Matsudaira.

The Nippu Jiji of Honolulu described Kinjiro’s family history and work as an executive at the Woodward Department store. The Nippu Jiji also emphasized Kinjiro’s physique as a “dark-haired, white complexioned and slender” Hapa, who “resembles a Japanese to be sure, but a good many of his countrymen who have met him could not be quite convinced.” The news of Matsudaira’s election even reached East Asia, where the election was mentioned in the pages of The South China Morning Post in Hong Kong and the Kaigai Shinbun in Japan.

Despite the historic nature of his election, the mayoralty seems to have been a part-time and unremunerative position, as Matsudaira kept his day job at Woodward & Lothrop. After his initial term, he left his position. Some time during this period, Ellen Matsudaira was appointed as a postmistress. Later she worked at Woodward’s.

In 1933, in the depths of the Great Depression, Matsudaira ran for the town council and was elected for a two-year term. However, he resigned the next year, for reasons lost to history (his son-in-law Malcolm Dent ran unopposed in a special election to fill his seat). In 1939, he was again a candidate for town council, but seems not to have been elected. Kinjiro Matsudaira retired from Woodward & Lothrop in 1950, and died in October 1963.

Today, Kinjiro Matsudaira is chiefly remembered as the sole Asian American to hold political office on the mainland before World War II. Yet, if his election represents an anomaly in American political history, his family’s presence in the community was not. Even after Kinjiro left office, he remained a resident of Edmonston. When the town was hit by floods in 1933 and 1955, he refused to abandon his home. An Evening Star reporter covering the 1955 flood noted that Kinjiro Matsudaira announced his intention to move upstairs until the flood abated, rather than to be evacuated. “Why do I want to leave. This is just the way we live.” The family remained a fixture in the Edmonston area after the death of its patriarch, and by the late 20th century four generations of Matsudairas had made their home there.

© 2021 Greg Robinson and Jonathan Van Harmelen