One remarkable story that comes out of the wartime removal and dispossession of Japanese Canadians is that of their exclusion at McGill University. In fall 1944, McGill, the historic university in Montreal, became the first Canadian institution of higher education officially to close its doors to Japanese Canadian students. Its action sparked widespread opposition, and led to the first visible public protest during the wartime period by non-Japanese Canadians on behalf of the citizenship rights of the Nisei. (While Tess Elsworthy’s recent McGill MA thesis, “McGill University’s Racial Exclusion of Japanese Students, 1943-1945” gives the definitive account of this story, this column draws from my previous independent research).

The events at McGill took place amid the background of increased Japanese Canadian wartime migration. From the time of their initial removal, West Coast Japanese Canadians began moving eastward. During 1942 and 1943, several hundred people, most of them young, unmarried Nisei, left the mass confinement sites in British Columbia where they had been initially confined. The trickle became a torrent following the government’s 1944 Order-in-Council requiring Japanese Canadians to relocate outside of British Columbia, as the majority of the country’s ethnic Japanese population accepted resettlement East of the Rockies. The largest fraction of migrants settled in agricultural areas in Ontario or near Toronto (whose Board of Control barred Japanese Canadians from residing within city limits until 1946).

About 10 percent of the migrants went to Quebec. The newcomers settled almost exclusively in the Montreal area, whose Japanese population reached 1247 by the end of 1946 and over 1300 in 1949, making it the largest Japanese community in the francophone world. A smaller number resettled in Farnham, in the Eastern Townships, where in the months after the end of World War II the federal government opened a hostel for resettlers in an old POW camp. However, most of those who came to Farnham eventually transitioned to Montreal or elsewhere.

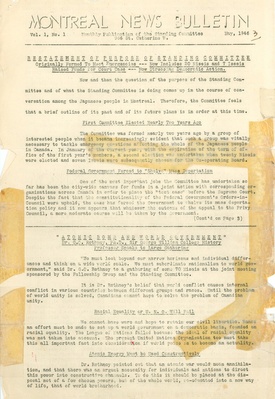

Once in Montreal, the Nisei formed a number of community institutions for mutual support and sociability. There were diverse church groups, such as the new Montreal branch of the Japanese Canadian United Church, as well as such social and athletic organizations as the (wonderfully-named) Montreal Nisei Mixed 5 Pin Bowling League. The Montreal Bulletin, a monthly community-produced newsletter, began publication in 1946 (and still continues!).

Various outside allies stepped up to assist the resettlers. Canon Percival S.C. Powles, a former Anglican missionary in Japan, helped direct relief efforts. The Catholic Church (which had sent priests and nuns to the confinement sites in British Columbia to open Catholic schools there after the Canadian government had refused to pay for public high schools for Nisei) also welcomed resettlers, especially Issei and Nisei Catholics. For example, the Sisters of Christ the King, a missionary order, opened a hostel for Japanese Canadian women. A significant fraction of Issei and Nisei found work in the garment factories of Montreal’s Jewish community, or rented housing from Jewish landlords.

Although Quebec remained the only Canadian province with a large Japanese population that did not impose any legal restrictions on them during the wartime era, Japanese Canadians in Montreal nevertheless encountered expressions of prejudice, both official and unofficial. Most notably, Premier Maurice Duplessis, a conservative French Canadian nationalist, refused to recognize Buddhism as a religious faith, which meant that Buddhist priests could not sign marriage contracts.

As Nisei settled in Quebec, students sought admission to McGill. In response, McGill’s Faculty Senate held a secret session in October 1943, in the course of which the members voted a blanket resolution barring all students of Japanese ancestry from admission.

The official rationale for the action was that since Nisei were not admissible for military training or for sensitive war work—Canada’s government had barred citizens of Japanese ancestry from enlistment even before Pearl Harbor—offering them a university education would be a waste of scarce facilities, and would constitute a form of discrimination against English Canadians who did not have the same opportunities due to military service.

Although McGill was already notorious for its longstanding discriminatory policies against ethnic/religious minorities (Jewish students, for example, were required to show proof of higher scholastic standing for admission than other applicants), this was an unprecedented action in its nakedly racist purpose and rationale. The Senate’s justification of avoiding discrimination was both false and disingenuous—women who were similarly barred from military service on gender grounds were nevertheless accepted as university students.

The university’s exclusion policy remained confidential for over a year. It was only in late October 1944, when the Alumni Association of the Montreal Diocesan Theological College (an Anglican theological seminary affiliated with McGill) found out about it, and enacted a resolution opposing the Senate’s action, that word of the exclusion policy spread to the Montreal Gazette and other mainstream newspapers (other than a small article in the Ottawa-based daily Le Droit, the francophone press seems not to have covered the exclusion policy).

The following week, the Toronto Globe and Mail reported on a meeting of teachers, professors, and students at Montreal High School in which M.J. Coldwell, the leader of Canada’s Social Democratic party, the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, was a guest speaker. When asked his opinion of McGill’s exclusion policy, Coldwell stated that any university that practiced such a policy “forfeits its right to be called a university,” and would be cut off from educational grants under a CCF government.

McGill students joined the chorus of protest against their university’s policy. On November 1, the Student Executive Council passed a motion expressing strong disapproval of the Senate Resolution and “respectfully” requesting the Senate to admit Nisei students.

A week later, on November 9, the McGill Student Labour Club (SLC) called a meeting to discuss the situation. The SLC call proclaimed “The action of the Senate constitutes a danger to the democratic right of all Canadian students to attend institutions of leaning.” The guest speaker at the meeting was Betty Kobayashi, a mixed-race Nisei activist who had attended McGill in the 1930s and served as a representative to the Canadian Students Assembly, where she had campaigned for a boycott against Japanese goods to protest Tokyo’s occupation of China.

According to the student newspaper McGill Daily, in her speech Ms. Kobayashi “expressed the conviction that only fighting for tolerance among all the peoples of Canada will vanquish intolerance and make possible the achievement of the common aims of all Canadians.” The meeting adopted a resolution opposing exclusion from the university of Japanese Canadians on racial grounds, and protesting any racial discrimination in the University.

On November 14, the McGill Students’ Society sponsored a mass meeting protesting the University’s exclusion policy, and voted unanimously to sponsor a petition calling for the lifting of exclusion. The petition was thereafter signed by 250 students. Other groups, such as the student Veterans’ Society, adopted their own resolutions against exclusion. Meanwhile, McGill Sociology professor Forrest La Violette (an American of French Canadian ancestry who was a prominent scholar of Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians) worked behind the scenes with Canon Powles and his family to organize opposition. In December the Montreal Presbytery of the United Church of Canada voted its own resolution.

Students at other universities soon joined in the condemnation of McGill. On October 27, The Varsity, the undergraduate publication at University of Toronto, denounced the exclusion: “The McGill Senate, by this [action], exposes itself to the charge of practicing at home the policies and practices the rest of the country is fighting abroad.” The editors took particular exception to the idea that students could legitimately be barred from education because of their exclusion from military service: “One mistaken and semi-Fascist regulation cannot be justified by pointing out another, equally mistaken.”

In November 1944, the Silhouette, the student newspaper at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario ran an editorial praising the resolutions of the Students’ Executive Council and the McGill Students’ Society as striking an important blow for democracy against racial discrimination: “Good Work McGill. Well Done.”

The editors likewise hailed the participation of such a large number of students in the meetings and “the diplomatic method and the sincere purpose, absent of hysteria and clamour” that they had shown. Nonetheless, even in the face of such pressure, the McGill Senate refused to rescind its policy. In early February 1945, the Queen’s Journal, the student newspaper at Queens University in Ontario, published an editorial scoring the McGill Senate’s exclusion policy as (sic) “bigotted”, and its leaders’ refusal to take account of the will of its students as a “grave menace to student democracy.”

The stalemate remained through the first half of 1945. Nonetheless, McGill eventually backpedaled. In August 1945 university officials announced that the ban on Japanese Canadians would be relaxed, though it put off again the admission of any new students until winter term 1946.

Japan’s surrender soon made obvious that wartime controls were no longer justifiable, and in autumn 1945 George Kobayashi became the first new Nisei student to enrol at McGill. By 1952, the Pacific Citizen noted proudly, there were 33 students of Japanese ancestry at McGill.

Despite the eventual reopening of the university, McGill’s exclusionary policy not only affected the Nisei whose desire to attend school there was frustrated, but touched the larger community, leaving a scar. In a parallel case, thanks to the leadership of scholar/activist Eric Langowski, Indiana University’s leaders have been forced to take account of their institution’s wartime exclusion of Nisei students. It is to be hoped that McGill will join its American counterpart in facing up to the burden of its own history.

© 2021 Greg Robinson