Bigotry towards Japanese immigrants in San Francisco climaxed on October 11, 1906 when the city’s Board of Education announced that “all Chinese, Japanese, and Korean children” would have to attend the newly formed Oriental School, located on Clay Street between Powell and Mission. This order to segregate the city’s schools drew sharp criticism through the U.S. and Japan, eventually prompting President Theodore Roosevelt to pressure the Board of Education to rescind the order. In exchange, in 1907 Roosevelt negotiated the Gentlemen’s Agreement with to limit Japanese immigration to the U.S.

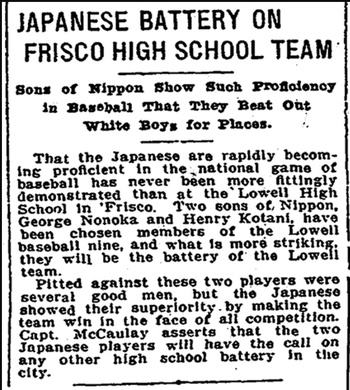

In light of the controversy over segregating the schools, newspapers across the United States ran a surprising story in late November and early December 1907. “Japanese Battery on Frisco High School Team,” proclaimed a headline in Seattle’s Daily Times (November 25, 1907, 11).

The article explained “that the Japanese are rapidly becoming proficient in the national game of baseball has never been more fittingly demonstrated than at Lowell High School in ‘Frisco. Two sons of Nippon, George Nonoka [actually Frank Nonaka] and Henry Kotani, have been chosen members of the Lowell baseball nine, and what is more striking, they will be the battery of the Lowell team.”

A later article noted, “This is the first instance in the history of interscholastic or intercollegiate baseball that the pitcher and catcher were Japanese. That the lads from the land of the rising sun are not far behind their American brothers in acquiring the gentle art of baseball is not to be doubted.” (SF Examiner, December 6, 1908, 26)

The pitcher, Masakazu “Frank” Nonaka, was Lowell’s ace from 1907 to 1909. Although he stood just 5’ 5” tall and weighed only 132 lbs., had one advantage over most opponents—he was much older (Masakazu Nonaka, Petition for Naturalization, Ancestry.com).

Born on May 28, 1885 in the town of Miyamoto in Niigata Prefecture, Nonaka had probably graduated from a Japanese high school before he immigrated to California in 1903. Nonaka disappears from the historical record for a couple of years until June 1905 when he graduated from Pacific Heights Grammar School and took out an advertisement in the San Francisco Chronicle stating, “A young trustworthy Japanese boy wants a position as a schoolboy. Frank Nonaka, 1824 Fell St.” (SF Chronicle, June 5, 1905; SF Call Bulletin, June 29, 1905).

In the Fall of 1905, he enrolled as a freshman at Lowell High School. Located adjacent to modern-day Chinatown, Lowell was the city’s oldest public secondary school and the top public college preparatory school. Nonaka made the varsity baseball team his freshman year, playing (but not pitching) against Polytechnic on April 7, 1906—just eleven days before the earthquake leveled the city (SF Call Bulletin, April 8, 1906). The next fall, his future batterymate Henry Kotani arrived at Lowell.

Kuraichi “Henry” Kotani was born in the Nihomachi section of Hiroshima on April 24, 1887. In 1896, his family immigrated to Honokaa, Hawaii, where his father, Iwakichi, would run a hotel (1900 Federal Census).

After 1900, Henry moved to San Francisco, where he graduated from Fremont Grammar School in January 1906, before enrolling at Lowell High School in the fall of 1907 (SF Call Bulletin, January 26, 1906).

As a freshman, Kotani became the starting guard on Lowell’s basketball team. He excelled at the game, playing on the team for three seasons, and was selected for “the all-star aggregation picked from the city’s schools” during the 1907-08 season (SF Examiner, Sept 13, 1908, 28). By his senior year, he was “considered as one of the best guards among the school teams of San Francisco” (Wood Daily Democrat, February 8, 1909, 1).

By the fall of 1907, Nonaka had emerged as Lowell’s top pitcher and Kotani had secured the role of the team’s backstop. On October 7, 1907 Nonaka took the mound and Kotani squatted behind the plate for the first time in an interscholastic game as Lowell topped Alameda High School, 8-7. For the next six weeks, the pair continued to lead the squad.

In mid-November, for example, Nonaka pitched a one-hitter against Alameda High School but “the surprise of the game was Kotani,” noted the SF Examiner on November 16. “He played a rattling good game behind the bat and hit the ball hard.”

The same newspaper noted, Nonaka and Kotani “have already made for themselves an excellent record in interscholastic athletics. Nonaka … is one of the most consistent players on the team. Unlike most twirlers, he is a good batter, seldom failing to get his share of the hits. … When not pitching he can play an outfield position to perfection he is a sure catcher of flies, and all kinds of drives and covers lots of ground. Kotani, his teammate, is a consistent backstop. While not ranked as a star, he always plays a good game. Few stolen bases have been charged up to him, his accurate throws almost most always cutting off any attempted steals. He is known as the [clutch] hitter of the team. Coming through with a [single] often at the proper time when hits are most needed” (SF Examiner, December 6, 1908).

At least one reporter made a direct connection between the city’s school board’s efforts to remove Asians from the white schools and Lowell’s Japanese battery—although he declined to take an explicit stance on the controversial topic. In his November 17, 1907 column “A Sportive Thought or Two,” Waldemar Young of the Examiner wrote “Nonaka and Henry Kotani two brown boys from the Land of Flower and Fan, will be the battery of the Lowell High School team in the coming baseball season. Let me see: What was that trouble the Board of Education started a year or so ago?”

What is surprising is the support the newspapers gave the players. At the time, open bigotry toward Japanese immigrants was especially high in San Francisco. For example, Nonaka recalled in a 1960s interview, being spat upon as he walked down the street just because he was Japanese (the tape of this interview is in the Japanese American Research Project Collection at UCLA but is inaccessible due to the Covid related closings).

The city’s newspapers openly supported anti-Japanese politicians and often used alarmist or derogatory language when describing Japanese immigrants. For example, the front page of the Oakland Examiner on October 7, 1907, the same issue that reported Lowell’s Japanese battery’s first game, contained the headline, “Government Moves to End Invasion of Japanese. Washington Alarmed at Number of Orientals Streaming Over Borders.” But in the sports pages both Nonaka and Kotani received only praise.

Lowell’s now famous Japanese battery did not last long. An injury sustained on the hardcourt, kept Kotani from playing on the diamond in the spring of 1908, although Nonaka enjoyed a stellar season. The SF Examiner noted on April 26, “Frank Nonaka, the Japanese curve artist of the Lowell High school baseball team, is rated among the best of the pitchers in the Academic League. Nonaka has been very successful in all of his games this season and has a good strike-out record. He has won all of his preliminary games and one league contest.” At season’s end, he was the runner-up for the city’s best scholastic pitcher (SF Examiner, June 21, 1908).

In the fall of 1908, Kotani decided to concentrate on basketball rather than divide his attention between two sports. Nonaka continued as the school’s ace, pitching well but was no longer considered one of the city’s top players. Both young men were also active in the Fuji Athletic Club. Founded in late 1903 or early 1904 by famed artist Chiura Obata, the club fielded the top Japanese sports teams in San Francisco. In January 1909, Kotani played quarterback and Nonaka right end as the Fuji lost to the Chinese Imperials in a match on the gridiron (Oakland Tribune, January 4, 1909).

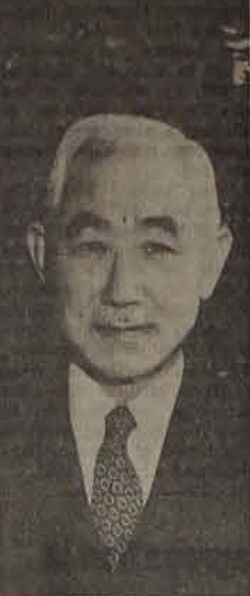

Nonaka seems to have stopped playing baseball after graduation. He attended business college, worked for the Okada Company, and eventually opened his own import-export company. His business flourished, allowing Nonaka to become a community leader and philanthropist before his death in 1967. Among Nonaka’s many contributions was a gift of 200 Japanese golden carp to Spreckle’s Lake in Golden State Park. The carps’ descendants still swim in the famous lake (Pacific Citizen, December 1, 1967, 4).

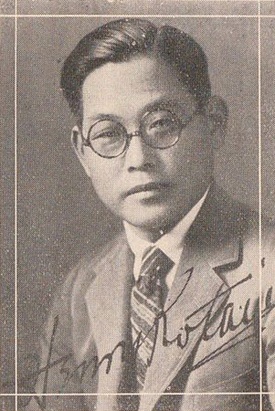

After graduation, Henry Kotani continued to play baseball and other sports for the Fuji Athletic Club for several seasons. In April 1911, playing against the visiting Waseda University club, he “drove out a clean two-base hit between the right and centerfielders in the fourth frame, and the brand of local Japanese rooters who made up the majority of the spectators rooted with all of the latest American baseball phrases” (SF Examiner, April 18, 1911, 10). But Kotani’s true passion was not baseball, or even basketball, but acting.

Henry’s first major role came in December 1908 when he played the butler in the Alcazar Players performance of “Brown of Harvard” (SF Call, December 22, 1908). He worked with the troupe for several years, playing various roles as Japanese or Chinese servants, before heading to Hollywood.

In 1914 and 1915, Kotani appeared in several films but soon moved behind the camera. In the late teens, he became a cinematographer for the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation. On the recommendation of Cecil B. DeMille, Kotani returned to Japan in 1920 to help Shochiku create a film company. As a director and cinematographer, he introduced modern Hollywood techniques to Japan, revolutionizing the industry. He remained in Japan and was honored with a lifetime achievement award by the Mainichi Film awards in 1960 and was presented the Order of the Sacred Treasure by Emperor Hirohito in 1964. Kotani died on April 8, 1972 (Henry Kotani, Wikipedia).

*This article was originally published on the Fitts Baseball History on March 17, 2021.

© 20201 Robert K. Fitts