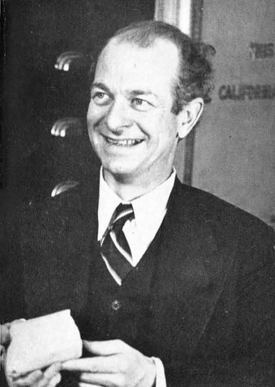

In a previous article for Discover Nikkei, I profiled the life work of Harvey Itano, the first Japanese American student to leave camp, who became a pioneering researcher of sickle-cell anemia. During his graduate studies at the California Institute of Technology (or Cal Tech), Itano worked with the distinguished scientist (and later two-time Nobel Prize winner) Linus Pauling. Although Pauling’s work as a scientist and peace activist is world-renowned, his experience living on the West Coast and serving as an advocate for Japanese Americans is less known.

Along with Cal Tech botanist Robert Emerson, who worked as a director for the Manzanar Guayule Project, Pauling was among the faculty at Cal Tech who supported Japanese Americans resettling in California in 1945-46. In the process, he personally was touched by racism, after anti-Japanese vandals targeted his house.

Linus Pauling was born in Portland, Oregon on February 28, 1901, the son of Herman Pauling, a German immigrant, and Lucy Darling. After growing up with a fascination for chemistry, Pauling earned his bachelor’s of science in chemical engineering at Oregon State University in 1922, and then enrolled as a doctoral student at Cal Tech. Pauling studied chemistry and physics under Roscoe Dickinson and Richard Tolman while at Cal Tech, where he completed his PhD in 1925. After completing research in Switzerland with funding from a Guggenheim Fellowship, Pauling began work as an assistant professor at Cal Tech in 1927, aged just 26 years old.

While Pauling presumably met and taught Nisei students at Cal Tech in the years before World War II, and by his own later testimony, he was emotionally affected by the forced removal of West Coast Japanese Americans, his exposure to anti-Asian racism during this period was limited. Rather, his career as a supporter of Japanese Americans started at the close of the war. In late February 1945, Pauling hired George Mimaki, a former resident of Gardena and then prisoner at Heart Mountain concentration camp, for work as a gardener at his home in Altadena, California.

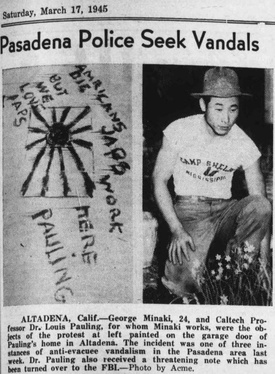

The hire gained a certain measure of local publicity. Mimaki told reporters that he planned to join the Army after a period working for Pauling, and he was photographed wearing a Camp Shelby shirt – the stateside base where Japanese American soldiers with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team trained. Sometime on the night of March 5th, an anonymous racist or racists vandalized the exterior of Pauling’s home. Pointing to Pauling’s employment of Mimaki, the vandals painted a Japanese flag on his garage, above the words “Americans Die But We Love Japs – Japs Work Here Pauling,” and also covered his mailbox with bright red paint.

Pauling responded to the attack by contacting the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s office for protection from further vandalism or violence. A deputy at the Sheriff’s office declined to help, stating that “this was just what we could expect if we employed Japs.” Pauling’s wife Ava then contacted the Los Angeles chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union and reported the official’s remarks. After pressure from the ACLU and the Fair Play Committee of the West Coast, Los Angeles Sheriff Eugene W. Biscailuz (who was notorious for his public advocacy of exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast) wrote to the Fair Play Committee offering his sincerest apologies and offering to ensure the “perpetrators are caught.” Soon thereafter, a sheriff was stationed outside the Pauling’s home for one week, during which time Pauling travelled to Washington, D.C. for national defense work.

The Los Angeles Times and Los Angeles Herald, as well as other mainstream newspapers, covered the incident, including photographs of the garage and snapshots of Pauling’s gardener George Mimaki (misspelled as Miniaki in some articles). (News of the incident also reported in an article by the New York Times on March 18th that mentioned the vandalism as part of a string of hate crimes against Japanese Americans throughout California). Whether out of thoughtlessness or malice, the Los Angeles newspapers included the addresses of Pauling and Mimaki in the text of their articles.

In the days following the incident, Pauling received a barrage of hate mail from racist Californians, many accusing him of aiding “the enemy.” Although some letters addressed to Pauling were sent to his Cal Tech office, the listing of Pauling’s home address may have led to an increase in hate mail sent there as well. One of the letters, later identified as sent by the original vandals, stated their intention to tar and feather Pauling and even “take care of you just like Al Capone did some years ago.” The arrival of such hate mail led local officials to contact the FBI.

In the Japanese American Citizens League’s weekly newspaper The Pacific Citizen, photos of the graffiti and George Mimaki were printed on the March 17th, 1945 issue, along with a reprint of the Los Angeles Times’s report. An article on the incident later appeared in the March 19th issue of the Utah Nippo. Nonetheless, press coverage of the hate crime in the Japanese American press remained limited—perhaps Nisei editors feared discouraging resettlers by publicizing hate crimes, or perhaps the incident was not sufficiently different from other incidents already reported.

Pauling refused to fire his gardener. He later publicly stated the graffiti was an “un-American act” carried out by “misguided people who believe American citizens should be persecuted in the same way that Nazis have persecuted Jewish citizens of Germany.” He continued to confront anti-Japanese racism. In a set of unpublished notes, he detailed an incident on October 5, 1945 when a Nisei woman, Helen Hoshino, told Pauling that during a trip to the Walker Grocery store in Pasadena, she was cursed out by a store clerk for being Japanese. Pauling went into the store and asked the clerk if the incident was true. Not only did the clerk willingly admit to it, but Pauling was then confronted by multiple customers saying that they would do the same if they could. Discouraged by such bigotry, he left the store.

A few months later, in April 1946, Pauling was contacted by E.A. Doisy of St. Louis University (who shared the 1943 Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery of vitamin K), who asked about having his prize student, Harvey Itano, work with Pauling. Pauling accepted Itano, and supported his application for funding from the American Chemical Society. Itano proceeded to work with Pauling on researching the chemical relationship between hemoglobin and sickle cell anemia. The work on sickle cell anemia, which climaxed in a groundbreaking 1949 joint paper in Science magazine, defined the careers of both men.

For Itano, it was the start of a career-long concentration on abnormal hemoglobins and blood diseases. For Pauling, whose scientific interests spanned many disciplines, including chemistry, physics, and medicine, the research was important in the development of his chemical and biochemical approach to treating human illnesses, which included his later advocacy of the use of vitamin C to prevent the common cold and, more controversially, cancer. While the sickle-cell research might well have been recognized with a Nobel Prize in either Chemistry or Medicine, it was only tangentially related to Pauling’s ground-breaking work on the nature of the chemical bond that led to his 1954 Chemistry Nobel Prize.

Pauling’s failure to properly credit Itano as a collaborator, including placing himself as the first author of the 1949 Science paper, which was primarily the work of Itano and another Cal Tech researcher, Jonathan Singer, was controversial. Itano’s election to the National Academy of Sciences in 1979 (he was the first Nisei to be so honored) might have been an effort to compensate for the slight. George Brecher, the famed hemotologist and founder of UCSF’s department of laboratory medicine, later wrote to Itano stating that Pauling had acted unfairly in comparison to other Nobel Prize winners like Max Born, who regularly credited his students.

While Pauling’s action was not uncommon among academics, his failure to share credit certainly affected Itano’s career negatively. Nonetheless, Pauling and Itano enjoyed a long, amiable relationship, even after they ceased working together. Pauling later hosted Itano’s sixty-fifth birthday party in 1985, and chipped in funds to offer Itano one of his lifelong desires – a complete set of the Encyclopedia Britannica.

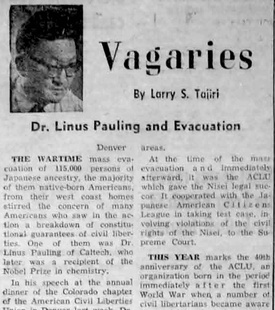

Even as the atomic bombing of Japan led Linus Pauling to take up his long campaign against nuclear proliferation, which would win him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1962, his wartime experience with anti-Japanese racial hatred on the West Coast was a watershed moment in his life. Perhaps the most illuminating comment on Pauling’s activism was made by Larry Tajiri, who profiled Pauling in his “Vagaries” column in the November 25th, 1960 issue of The Pacific Citizen.

Tajiri begins his story with a statement made by Pauling at a meeting of the ACLU’s Denver chapter, to the effect that the forced removal of Japanese Americans made him aware of the dangers to the civil liberties of all Americans. Chemist and writer Jeffrey Kovac later affirmed that the incident was fundamental to Pauling’s politicization, stating that as a witness (and a victim) to a hate crime and to the development of nuclear weapons during the war shook his conscience.

It seems clear that Linus Pauling’s experience in Los Angeles in the period surrounding the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans exposed him to the horrors of racism, helping shape Pauling into the renowned peace activist he became. It may also have helped inspire him to champion the work of Nisei scientists such as Harvey Itano, whose collaboration would bring Pauling rich rewards.

Author's note: Special thanks to Wayne Itano for his help with this article.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen