It was the middle of December 1935. The Nippon Yusen liner Asama Maru had just concluded a fourteen-day voyage. After leaving Yokohama and stopping at a port of call in Honolulu, it arrived in San Francisco. As Asama Maru sailed into San Francisco Bay, its 800 passengers looked on, no doubt thinking of the ventures and reunions that lay ahead. Among the crowd on deck was a 47 year-old Japanese man whose entry into the United States was unexpectedly halted. He was discovered to have trachoma—an infection of the eye that, if untreated, leads to inflammation and blindness—and was summarily taken off the boat by the Public Health Service and sent to Angel Island for isolation.

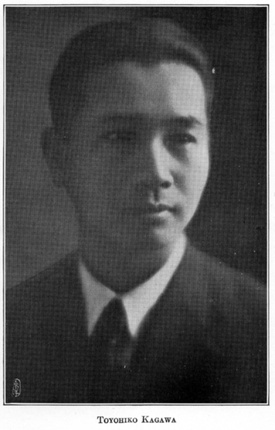

Though the passenger may not have appreciated the historical irony of his destination, the Angel Island immigration station had been the main gateway and official detention center for countless Japanese entering the United States over previous decades. What is more, in early twentieth-century America, trachoma carried a powerful social stigma as an “immigrant disease,” associated with impoverished foreigners. Yet the unfortunate man thus detained was neither an immigrant nor from a poor background. Rather, he was Dr. Toyohiko Kagawa, a world-famous Japanese Christian evangelist, writer, and social reformer, who had been invited by American supporters to make a six-month lecture tour of the United States, and who was scheduled to be guest of honor at a special welcome luncheon organized by the mayor of San Francisco.

It is perhaps difficult for readers in the 21st century, when Toyohiko Kagawa’s name has faded, to appreciate the level of international celebrity that he enjoyed during his lifetime. Kagawa was often mentioned in the same breath as Gandhi, as a charismatic and even saintly leader who brought his religious faith into politics and social reform, but who did not speak as a theologian. Like Gandhi, he was a prominent critic of industrial capitalism. Kagawa’s groundbreaking work as labor organizer and founder of the Japanese consumer cooperative movement made him an influential voice for social and economic justice. He also stood out as an advocate of international peace, especially in a period when militarism dominated Japan. A prolific writer, Kagawa published a reported 150 books during his lifetime. He was nominated five times for the Nobel Prize, both for literature and the Nobel Peace Prize.

Born in Kobe in 1888, the son of a shipping merchant and his concubine, Toyohiko Kagawa lost both parents at a young age, and endured a lonely childhood. Finding solace in the company of Harry W. Myers and Charles A. Logan, Presbyterian missionaries from America who ran an English Bible class for Japanese youth, he was baptized by their hands as a teenager. Under their guidance, he attended Meiji Gakuin, a Presbyterian college in Tokyo, then enrolled at Kobe Theological Seminary.

It was in 1909, while at the Seminary, that he took up residence in a shed in the Shinkawa slums of Kobe and became involved in relief work aiding thousands of poor residents, a mission dramatized through his 1920 autobiographical novel, Shisen o koete [Across the Death-line]. (It was during his time in the Kobe slums that Kagawa picked up his aforementioned eye infection).

In the years following World War I, Kagawa took a lead in organizing unions for industrial laborers, founded the Kobe Consumer Co-operative, and worked for universal suffrage in Japan.

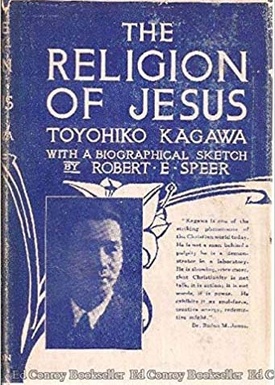

In 1921, he and a group of supporters founded the Friends of Jesus, a Franciscan-style Christian fellowship organization whose members strove for spiritual discipline and compassion for the poor. In works such as The Religion of Jesus (1931), Kagawa underlined the redemptive love of God, and the importance of individual commitment to Jesus Christ.

Kagawa’s relationship with the United States dated back to 1914, when he left his humble dwellings in Kobe to study at Princeton Theological Seminary. Kagawa spent three years at Princeton before returning to Japan. He revisited the United States from late 1924 to early 1925 to attend the Pan Pacific Student Convention and conduct a short speaking tour.

Japanese American communities in Hawai’i and southern California welcomed his visit, and went so far as to establish local branches of the Friends of Jesus. Kagawa made a subsequent tour in 1931.

During this trip, he was invited to deliver the prestigious Shaffer lectures at the Yale Divinity School, which described Kagawa as “one of the greatest and most influential of modern Christians.” During his absences, Kagawa’s missionary supporters in the United States, most notably Helen Topping and her family, further cultivated his image as an international Christian and pacifist figure by producing a stream of English-language publications and promotional materials by and about Kagawa, which were distributed to domestic American audiences as well as to mission stations around the world. Several of Kagawa’s books, including The Religion of Jesus, the novels Before the Dawn (1925) and A Grain of Wheat (1936), the essay collection Love; The Law of Life (1928) and even a volume of poetry, Songs from the Slums (1935), appeared in translated editions by American publishers.

Kagawa’s arrival in San Francisco in December 1935, and his detention by immigration authorities, mobilized his supporters. Stanley A. Hunter, pastor of St. John’s Presbyterian Church in Berkeley and one of Kagawa’s most ardent collaborators, visited him at Angel Island and explained that “U.S. veteran’s associations” and “retailers’ unions” were protesting his arrival by sending cables and letters to immigration officials. Convinced that Kagawa was being unfairly targeted for his pacifism and cooperative economic theories, Hunter lodged an appeal on his behalf, which was joined by the members of the coordinating committee in charge of Kagawa’s American itinerary.

The campaign attracted widespread news coverage. Sympathetic commentators noted the irony that the “St. Francis of Japan” had been denied entry at the port of “San Francisco,” as a direct consequence of his self-sacrificial service for the less fortunate. Time magazine called him the “Quarantined Christian.” The news coverage, plus a telegram from John R. Mott, international president of the YMCA, caught the attention of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. FDR expressed a “personal interest” in Kagawa’s case, leading the immigration board to grant Kagawa admission to the United States, on the condition that he be accompanied by a physician or nurse while in the country.

These events, and the President’s action, further bolstered public interest in Kagawa and his message, and Americans flocked to hear Kagawa’s speeches during his tour. A telling event was his March 4, 1936, appearance in Cleveland, Ohio. The general secretary of the Cleveland YMCA compared Kagawa’s visit to the Eucharistic Congress—which had been held recently in the same city—in terms of the scale and excitement generated: “One event was in the nature of a mammoth religious convention [for Roman Catholics] lasting almost a week; the other consisted simply of four meetings on a given day with overflow audiences in each.” The crowd’s sole object of interest was a “humble Japanese Christian,” he continued, “[who] said nothing very striking,” nor revealed any “new or startling truths.” Nevertheless, he concluded, the attendees were keenly drawn to the itinerant evangelist’s embodiment of a “simple life, absolutely and unconditionally dedicated to the service of humanity in the name and spirit of Jesus Christ.”

When Kagawa visited Springfield, Illinois, in February 1936, Albert Palmer of the Chicago Church Federation made a Lincoln’s birthday radio address explicitly linking the Japanese evangelist to the Great Emancipator. (Palmer’s address inspired Helen Topping and other supporters to compile a pamphlet volume of essays and speeches titled, “Kagawa in Lincoln’s Land.”)

As previously, Kagawa’s reception among Japanese American communities on the West Coast was particularly warm. Issei and Nisei were excited to receive a Japanese who was an international celebrity. The English-language press provided widespread coverage of Kagawa’s activities.

After arriving on May 24 in Los Angeles, where he was greeted by the local Friends of Jesus group, he embarked on a ten-day schedule of lectures in southern California. His speech to Nisei Christians precipitated a widespread cancellation of regular sporting and recreational events to ensure that all young people could attend. That the youth were asked to refrain from requesting autographs or shaking hands with Kagawa attested to his star status, while the announcement that transportation would be provided to his lecture venues underscored the community’s involvement and investment in his tour.

The timing of the tour, with the United States in the throes of the Great Depression, fostered a ready audience for Kagawa’s interpretation of the Social Gospel. This was apparent in the tour’s highlight: his mid-April visit to the Colgate-Rochester Divinity School in upstate New York, where he delivered the prestigious Rauschenbusch lectures (a series named after the Baptist theologian and Social Gospel leader Walter Rauschenbusch). Kagawa’s lectures drew connections between the spirit of sacrifice as personified by Jesus Christ, and the spirit of social solidarity as exemplified by the cooperative system of non-exploitation and mutual aid. The lectures were later adapted into a book, Brotherhood Economics, which was subsequently translated into seventeen languages and sold in twenty-five countries.

Kagawa’s tour also became a rallying point for advocates of equal rights for Japanese Americans. The Federal Council of Churches (FCC), the official sponsors for Kagawa’s tour, saw the event as part of their longstanding opposition to the United States’ legal exclusion of Japanese immigrants. Organizations such as the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) gathered signatures on pledge cards seeking repeal of exclusion. Allan Hunter, the L.A.-based FOR organizer and younger brother of Stanley Hunter, proudly reported the signing of “several thousand” pledge cards, which they presented to Kagawa during the latter’s stay in southern California. The FCC continued to call for the repeal of the “Asian Exclusion Law” after the tour, stating in their 1936 year-end report that the free exchange of ideas represented by the “Christian ambassador” Kagawa should be furthered.

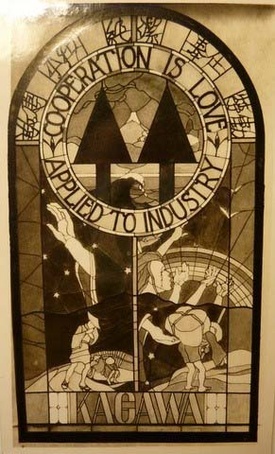

Following Kagawa’s departure in June 1936, the pastor of the Community Church in Grant, Michigan, decided to memorialize Kagawa in the form of a stained-glass window, thus providing a fitting coda to the Japanese evangelist’s celebrated visit. The Kagawa Memorial Window, unveiled in December 1936, was installed as the first in a series of seven that paid tribute to “modern major prophets.” Its design, inspired by Julian Brazelton’s illustrations for Songs from the Slums, featured the phrase, “Cooperation is love applied to industry,” with Japanese characters for the five tenets of the Friends of Jesus—devotion (keiken), peace (heiwa), purity (junketsu), service (hōshi), and labor (rōdō)—across the top, and depictions of Japanese farmers and laborers above the letters, “KAGAWA”, on the bottom. The memorial window visually and symbolically encapsulated the sanctification of Kagawa and his teachings among his most ardent American supporters.

Following his return to Japan, Kagawa continued his writing and advocacy of social reform and international peace. In August 1940, he was briefly imprisoned for a public apology he had made six years earlier on behalf of the Japanese people for his country’s aggression in China. The next year, he revisited the United States, first as a member of the 1941 Japanese Christian Peace Delegation (Nichibei Kirisutokyō heiwa shisetsudan) and then on an independent speaking tour. He was unable to calm U.S.-Japanese tensions, which broke out into war three months after his return. He made further tours of the United States during the 1950s, and was again warmly greeted by Japanese American audiences. He died in 1960.

Toyohiko Kagawa’s social reformism and work with economic cooperatives served as a model for implementing the teachings of the social gospel. His advocacy of labor rights, consumer co-operatives and universal suffrage mark him as a figure ahead of his time. His cosmopolitan outlook and opposition to war, moreover, made him an appealing advocate for racial reconciliation and world peace.

© 2021 Greg Robinson & Bo Tao