“It was a struggle because once we got to the point where we could live in that little house that they built, everything was happy. And then this war happens, and they’re taken from their comfort.”

— Mary Iwami

Mary (Idemoto) Iwami remembers the day her parents’ life changed permanently and seemingly in an instant, disrupting their life as farmers in the agricultural sprawl of Salinas, California. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, FBI agents came to their home to warn Mary’s father to get rid of anything that could link them back to Japan or reveal their sympathies to their birth country. Like many first generation Issei, the decision to keep Japanese mementos or discard them was a simple one — proving faithfulness to their adopted American homeland took precedence.

Mary’s experience of being uprooted and living in two camps is told through the eyes of an eight-year-old child who remembers with nostalgic detail the home, one built from the ground up by her father, they were forced to leave behind. As she bore witness to watching her parents’ modest life fall apart, Mary today remains in awe of her father’s stoic, silent strength to carry on. “He rarely showed any frustration. I never heard him yell but a certain look and a few words told us what he felt. I truly admired him.”

* * * * *

What was your childhood like, and can you talk about some of your most vivid memories of growing up in Salinas?

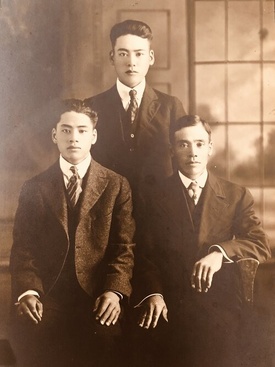

My father, Kenji Idemoto and his brother Mitsuru Idemoto came to America in 1918 when they were 18 and 16 years old, respectively, from Hiroshima, Japan. It must have been a difficult decision to make leaving security and family at such a young age and to come where language, customs, and a way of life are so different. They settled in Long Beach, California, and moved to various locations where work was available.

After many years, he married my mother, Fujiye Matsuda, in January 1934 by arrangement of the two families in Japan, and did not see each other until she came here from Japan. My father was 34, 14 years older than mother who was days short of being 20 years old.

I don’t recall details of our life except that my father worked hard and mom was a homemaker. We lived in Salinas, California. My father was a nice, quiet, reserved man of few words who I always admired and respected. My mother was outgoing and more social.

I was born December 20, 1934, and have three brothers: Akio born October 1936, Kunio born in February 1938, and Tom (Yoshitake) born in July 1941. He’s the only one who has an English name because his Japanese name was too hard to say. We had a dog named Jimmy who was collared to a long chain to the outdoor laundry line and had the freedom to run the length of it. Occasionally he was allowed to be free but enjoyed chasing the chickens too much.

What do you recall about the community and neighborhood that you grew up in?

I remember we had family friends who lived very close by. We attended the Buddhist church in town on Sundays and life felt secure. I have a panorama photo of about 170 church members standing outside of the Salinas church bell tower taken in 1934 before I was born. For a small town, that is a large number in membership.

I remember during my first grade, my teacher Mrs. Clark came to my home and asked permission from my parents so I could go on a trip with her to another school in King City (which was not too far away) to draw and paint a mural. There were other children involved, too. Although I don’t remember what I drew, I recall coming home after dark and my parents were very grateful that Mrs. Clark took such kind care of me. I actually remember her carrying me out of the car. And when she knocked on the door, Mom and Dad were there waiting and they knew how kind she was because I was in her arms — I was asleep. I can still recall Mrs. Clark’s pretty face and her smile.

As a young child, I was grateful that we had a nice family and supporting close friends. We lived in a very old farm house but in time we moved into a new home. One of the most impressive things in the house was a new, maroon velvet sofa. That really was something I thought about for many years. It was almost magenta colored. We children were not allowed to sit on it until we had bathed.

I did not know at the time that the fathers had decided each of the families needed new residences. The men folks had built five new homes prior to 1938. So I have pictures of the old home and the new home — and we had indoor plumbing, a modern toilet, and a small living room, a kitchen, and two bedrooms. I remember how proud I was of that beautiful sofa with a palm plant next to it and I always recall that and used to think, “Well, we did alright,” when my folks were really having a hard time. It was a nice reference to make.

Did they own their land or did they lease it?

No, my father worked for a big farmer called Yuki Farmers. And I think these other families also worked in that kind of capacity, it was a large family. And to this day I think their generation has continued.

My father built a Japanese outdoor bathhouse called the ofuro, for soaking after cleansing our bodies. Wood burning fire beneath the tub turned it into a very hot rectangular tub of water. Children were not allowed in the bathhouse unless Father or Mother was there.

However, the worst possible had happened. My father used to go to the bathhouse, get some water, add some water to it, and wash his face and hands before dinner. Daily, my father washed up for dinner by filling a pan of hot water and added cold water to soap and wash his face and hands. Well this one instance, my brother, Kunio, who was about three years old followed after my father had left the bathhouse. I happened to be in the yard when Kunio came out screaming and crying, pulling his sweater off his arm, and off came melted skin with it. I will never forget that scene. I don’t know what degrees of burns but I think it was fourth degree burns and required a hospital stay. It took a while for it to recover with bandages, and we had to guard against infection. It was about the time when war became imminent. Surgery on Kunio’s fingers was required but that had to wait. So the arm became scarred of course, but all of the curving of the hand remained the way it was all through Poston.

So this happened in about 1941, right before the war?

I don’t know what time of the year, but it was between ‘41 and ‘42 because he was in the hospital for a good month and we missed him. But his arms were bent and curled because both arms hit the water, and he was able to back out. And some of the water got on his legs. But he was only three years old, so he had tiny limbs. I think about that and I talked to him the other day and I asked him, “What do you remember about that?” And he said, “Well it’s a good thing we went to Tule Lake because the doctor there was a very special plastic surgeon.” So that helped. He was a Japanese doctor, too.

Your parents must have been so worried about how they would get him help.

Oh yeah, right. I think before we were leaving my father may have asked about that but I don’t know. I don’t think there was anything they could do. They said we had to go.

It wasn’t long afterwards that we had a visit from government officials directing us to bury any relics or pictures that related to the emperor or empress of Japan, and giving my father directives to move to an assembly center for all Japanese people due to the outbreak of war. Following these directives, he began cutting a picture of me out of a photograph of rows of dolls that were in the background which made up the royal court, with the emperor and empress at the very top. So he cut me out, then had to discard the pictures of the royal court. I saw him dig a hole in the ground and bury many things which I wanted, but now unable to keep. That was so sad. So I have the picture when I was a year old, with no background.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on December 25, 2020.

© 2020 Emiko Tsuchida