In February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the internment of more than 120,000 people living in the Pacific Coast states in10 internment camps. The order came just two months after the U.S. declared war on Japan.

Of those interned in the camps, 40,000 were Japanese citizens who had settled in California, Oregon, and Washington since the late 19th century and largely worked as fishermen, farmers, laborers, or storekeepers. By the time they were sent to the camps, most had already formed families and communities that were completely integrated into the U.S. economy. Despite the racism these immigrants faced, they had no intention of returning to Japan; on the contrary, they sought U.S. citizenship but were denied that right by the government, which viewed them as potential “contaminants” of white purity who did not fit with the country’s plans.

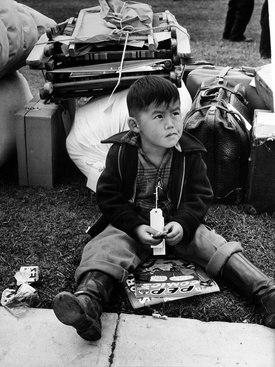

Most of the people sent to the internment camps—close to 80,000 people—were the children of immigrants and American citizens by birth. The youngest attended elementary school, where they pledged allegiance to the flag and sang the national anthem. The older ones worked or attended college and considered themselves fully integrated into American society.

What differentiated these children and young people from the rest of the population were their physical characteristics. Thus, even before the U.S. declared war on Japan, they began to be considered “enemies” of the country of their birth and of which they felt a sense of pride. To General John DeWitt, in charge of defending the Pacific Coast against a possible attack by the Japanese navy, it didn’t matter that these people were U.S. citizens. He believed that Japanese blood coursed through their veins, reason enough to force them into internment camps.

It is important to remember, however, that these policies, ideas, and biases existed throughout America, to such an extent that more than 2,000 Japanese immigrants and their families from 13 Latin American nations were essentially kidnapped and sent to the U.S. internment camps.

As part of the great alliance led by the United States, most Latin American governments broke off relations and declared war on Japan. By the end of 1941, Latin America was home to close to 300,000 Japanese immigrants who had formed extensive families and communities and put down roots largely in Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina.

These immigrants and their children, against their will and despite not being members of the two armies at war, became part of the war itself. Newspapers and radio programs, without any evidence at all, spread stories that these workers were spies, members of the “fifth column”. They were even accused of being part of the Japanese imperial navy preparing to invade the coasts of the American continent.

Throughout the continent, the war against Japan was in large part a battle against these immigrants and their children. But it is important to emphasize that this war did not begin in December 1941 when the Japanese navy, commanded by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, attacked the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor. Surveillance and persecution of Japanese immigrants by the U.S. government had begun early in the 20th century, when waves of immigrants began arriving in large numbers to various countries on the continent. By 1910, both Mexico and Peru were home to close to 10,000 immigrants, while close to 5,000 were living in Brazil and more than 50,000 lived in the United States.

Starting at that time, the U.S. War Department instructed its embassies throughout Latin America to provide information about the number and activities of Japanese workers. Monitoring by various agencies of the U.S. government was not only driven by racial prejudice, but was also related to Japan’s growing military and political significance and the escalating conflict between the two powers, which eventually led to Pearl Harbor.

With the rise of fascism in Europe and aggravation of the conflict between the U.S. and Japan in the 1930s, President Roosevelt designed a “continental defense” policy that sought to safeguard the continent from possible attacks by Germany or Japan, “from the North Pole to Patagonia”. To set this strategy in motion, the United States abandoned the “big stick” approach and promised not to invade the region’s countries, as it had already done numerous times. Thus, in December 1938, during the Eighth Conference of American States in Lima, the parties signed a “continental solidarity” pact that also implied surveillance of foreign citizens, primarily German and Japanese.

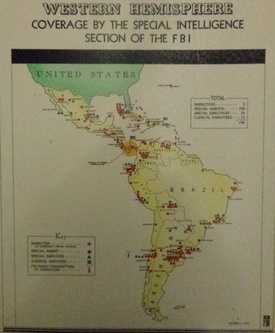

Despite the signing of this pact, the U.S. government wanted more assurance and in July 1940 President Roosevelt ordered FBI agents to be stationed in its embassies in Latin America as “legal attachés”, for the purpose of carrying out its own surveillance of Japanese immigrants and gathering intelligence information.

When war broke out, with the information provided by these agents and other intelligence sources, the U.S. government demanded that Latin American governments send Japanese immigrants to the internment camps; it also demanded that they be concentrated in specific areas where they could be monitored. In Mexico, President Manuel Ávila Camacho’s government forced immigrant families to move to Guadalajara and Mexico City to keep a close eye on them. The first to be relocated were those living in the Mexican states along the U.S. border.

In Brazil, the population of Japanese immigrants and their families had grown to 250,000. The vast majority of these immigrants worked in agriculture, which was of great importance and essential to the country’s economy. For this reason, they were not concentrated in specific areas, although they continued to be harassed and monitored by the Brazilian police, suffering profound limitations of their civil rights.

The case of Peru is undoubtedly the most tragic. The government confiscated businesses and other property owned by immigrants who hadn’t been sent to internment camps, leaving them without a source of income. Schools that had been established by immigrants were prohibited, forcing children to attend classes clandestinely in precarious conditions. Persecuted and hiding to avoid deportation, for these immigrants the war was a dark period of considerable desperation and anguish.

Decisions made by governments throughout the Americas profoundly affected and transformed the daily life of all immigrant families. Although they had left Japan decades earlier, these workers still had strong ties to their country of origin, since their parents, siblings, and other relatives remained there. At the same time, they were enormously grateful to the countries that had taken them in. They had succeeded in building extensive ties to the societies in which they flourished, but more importantly, these were the countries where their children had been born and raised, and of which they were exemplary citizens.

The war, internment, and persecution upset the delicate balance maintained by these transnational citizens, causing them not only substantial material harm but more importantly, affecting their emotional identity and ties to both Japan and the countries where they had settled. Under these circumstances, deep divisions began to appear within these communities, and even within the same families.

As this history shows, Executive Order 9066, which was aimed at immigrants and their descendants in the United States, covered the entire continent with its tragic shroud. Thus far, only the U.S. government has publicly apologized and paid reparations to those who were affected within its borders, thanks to the efforts of the same children of immigrants. However, on a continental level the consequences of U.S. policy toward Japanese immigrants have barely been acknowledged.

© 2021 Sergio Hernández Galindo