Nikkei poetry has a long history in Peru, starting with classic authors such as José Watanabe or Doris Moromisato, whose collections of poems date back to the seventies and eighties. In subsequent years, other authors such as Juan de la Fuente Umetsu have followed an aesthetic with a notable Japanese influence, the same that has inspired other Peruvian poets without Japanese ancestry such as Diego Sánchez Barreto and Alonso Belaunde Degregori, who are closer to haiku.

In recent times, Nikkei poetry has been charting new paths that flow in different directions like winds that follow their own paths. One of the most experimental Nikkei poets is Tilsa Otta, whose first collection of poems ( My poison girl in the garden of the ballads of memory , Album of the Bakterial Universe, 2004) mixes poems, stories and her own illustrations; very in line with the multifaceted creative personality of the author, who has also experimented with novels, comics and audiovisuals.

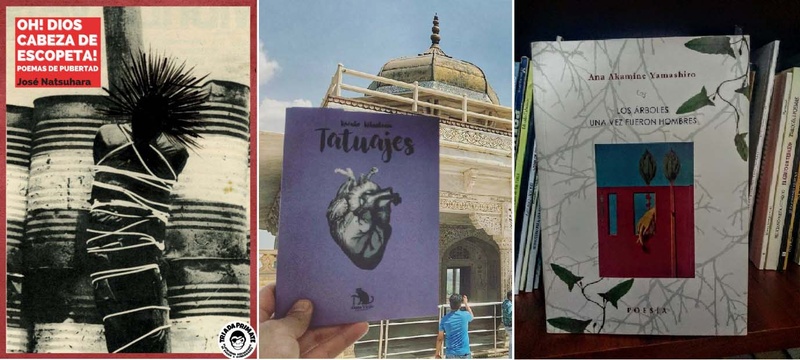

Some authors have followed this multiple path, while others have delved into a facet that, like any style, is difficult to pigeonhole. Poets such as Ana Akamine Yamashiro, Kazuko Kikushima and José Natsuhara have created much of their poetics in the last ten years and, without necessarily forming a generation or movement, they can help understand the new winds of Nikkei poetry that highlights or dispenses with its Japanese ancestry, but without separating it from his personal identity.

* * * * *

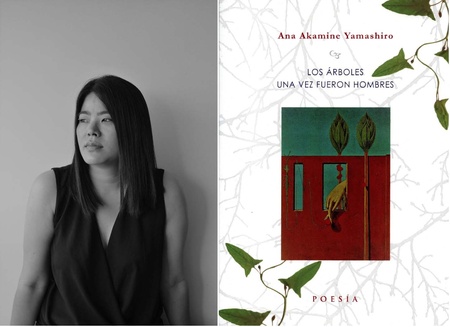

Ana Akamine

Since she was little, Ana Akamine's parents encouraged her to read. However, it was with the baroque poets that he discovered beauty in poetry; its musicality, sound and spectacular images that are shown in the new ways of using language. “They opened a world for me. Since I was right, reading was everything, and it still is,” says the author, who has not had training in literature, except for some poetry and narrative workshops.

In 2013, she won second place in the floral games organized by the Center for Literature Students (CELIT) of the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, and in 2015 she received an honorable mention in the Tale of 1000 Words from Caretas magazine. Two years later, she won theVI National Women's Poetry Contest Scriptura 2017 , organized by the Women Writers Commission of the PEN International of Peru and the Ricardo Palma University, for her collection of poems “The trees once were men”, published by the Carpe publishing house. Diem (2018).

“I am surprised by the number of editorials that appear and the dissemination of art is applauded, but sometimes I see that there are groups that take advantage of the need to express on the part of writers and publish without filter: bad editions, misspellings or questionable literary criteria where the desire to sell is evident. For example, while I celebrate that there are more and more workshops and spaces where people can develop creatively, the final product is publication. It is not the production of quality materials, but the publication. “Dissemination is confused with sales.”

Kazuko Kikushima

Kazuko Kikushima is a psychologist and communicator, which has led her to develop various facets such as holistic therapy, advertising and photography. “I considered myself shy, it was much easier for me to communicate my ideas by writing than by talking to people.” He began writing about people and for his first book of poems titled Tattoos , he sought a subtle mix between the tender and the suggestive. Kazuko Kazuko Kikushima.”

In October of that same year she was invited to participate in the 4th. Poetry Caravan Festival in Lima, and in November he participated in the II Tarma International Book Fair 2017 to present his book and hold a haikus workshop. A year later, he published some poems in the Peruvian fanzine “Poetas del Asfalto”. In 2019 she was selected to participate in the 2nd Nikkei Art Fair, Peru Gambarimasho, with merchandising created from her verses.

“I had some texts from when I was 15 years old. In Tatuajes there are poems about love and heartbreak, and I also thought about what I could say from my part as a psychologist. If it is worth continuing with a relationship or it is better to end it and heal, for example,” says Kazuko, who has seen self-publishing as her next direction. “In poetry, the publisher and the author end up doing the advertising. For me, self-management is better because you can connect with the public more directly. Plus, they make you feel their support.”

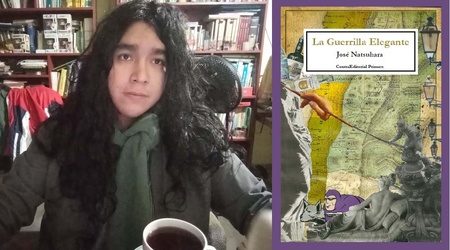

Joseph Natsuhara

For José Natsuhara, poetry came naturally, without intermediaries, since no one in his family is linked to literature. “I played at writing, I filled notebooks and then I began to take it more seriously, but not so seriously, because you start dedicating yourself to writing for others and that ruins your own writing, you write to be liked.” He studied philosophy, electrical engineering and psychology, and directed the magazine “Monologue”. Now he is in charge of the magazine “Primate” and the fanzine “a-ISLA(miento)”.

Self-taught poet and editor (his label is Triada Primate ), he has published the collections of poems: Oh! Shotgun-Headed God (2020) and The Elegant Guerrilla (2020), both of which are free to access through their virtual catalogue . In his verses various spiritual aspects are manifested that he absorbs from every source within his reach. In Bolivia, his work has been published by Trilce Chávez, under the title “Metaphysical keys that open unsuspected legs” (2018).

“I think it is important to find your own voice, to say something that is sincere. Sometimes when you find it, you talk about a formula and two things happen: you fall into repetition or you continue experimenting. I prefer the second. I make use of references of all kinds and, at the same time, I give it a structure that allows the elucidation of a thesis. Every poem is a thesis, beauty is a science for me.”

Nikkei identity

There is something about young and not-so-young Nikkei poets that leads them to relate to their Japanese ancestry in a different way than their predecessors, authors who perhaps had greater contact with the historical events linked to migration. Although with different approaches, these authors give, show and externalize forms that are identifiable with the country of their ancestors in combination, of course, with its Peruvian aspect and the cultural influence of globalization.

Ana Akamine says she feels enormous debts to the anonymous Spanish romances and to contemporary poetry. More than authors, she prefers to talk about styles: from the baroque to modernism and surrealism. “But if you tell me a narrator and a poet: Borges and Lorca.” In the case of Nikkei poetry, “the interesting thing is that I found poetic spaces where I felt fully identified. Nikkei society is closed and rich. This makes the culture shock when one goes abroad evident. I see it from melancholy.”

Kazuko Kikushima also has references from inside and outside the country: José Watanabe and the Venezuelan poet Gustavo Pereira. “Since 2018 I began to change my style by reading other authors who are not as commercial, with a more contemplative perspective like Watanabe's. Describing a landscape or a situation is more fun than writing something cheesy. Create scenes and think about where this comes from.” Of his Japanese origin, he says he maintains certain forms related to decency. “Now there are artists who go out with little clothing or are involved in scandals. “I think part of my Nikkei identity leads me to maintain honor and other values that are aligned with what our ancestors taught us.”

José Natsuhara claims to practice dokkodo, “the path of solitude,” a series of disciplinary and spiritual precepts written by the samurai Miyamoto Musashi, in addition to having the Zen monk Ikkyū as one of his greatest influences. Among his favorite poets he points out Abraham Valdelomar, Blanca Varela, the Bolivian Hilda Mundy and the Peruvian Tomás Ruiz Cruzado. “Family experience greatly influences my work, I have grown up with the stories of Japanese immigration. The figure of my grandmother has marked me a lot.”

Future poems

Currently, Ana Akamine is working on a new collection of poems, in addition to having others published in digital and printed magazines, and participating in recitals. “I don't think I address the issue of Nikkei identity in my poetry. However, it is inherent to me, it is in my psyche, my actions and in the way I see and understand the world. I have experienced the transgressions of differential treatment and it has made me more critical and socially aware. Art must be transgressive, literature as art is a permanent criticism of the social with intention or not, otherwise it remains only in the aesthetic and does not transcend.”

Recently, Kazuko Kikushima moved to Trujillo, José Watanabe's city, but she has been working in poetic collaboration with musicians since before. His second book is actually a “poetic playlist” that already has a part available on Spotify and will have bonus tracks. Musicians such as No Recommendable, Leonel Bravo and Hans Gamarra, among others, have participated there, with rhythms that fuse the author's song, reggae and other rhythms. “For the printed edition it will be an interactive book, with a QR code on each page. Read a poem listening to a song. Collaborations with these musicians create a new way of consuming poetry and opening up to new audiences.”

For José Natsuhara, all his work is structured around Zen spirituality. “I know the history of Japanese migrants in Pisco and I want to capture it in a book. I do it for a personal reason, more than to fit into a certain group,” says the poet, using José Watanabe as a reference. “I think the attractive thing is that he doesn't force a Japanese or Peruvian discourse, he writes what he feels. A risk within Nikkei poetry is falling into the label itself, trying too hard to propose a product and neglecting the background.” He is currently working on an ambitious project: a “Map of Peru”, a poetic anthology of each region of the country.

© 2021 Javier García Wong-Kit