If we were going to go back to fill in some of the gaps, after the loyalty questionnaire, were you drafted or did you volunteer?

I was drafted. After I got out of high school and camp, I went out to the University of Cincinnati. The American Friends Service Committee provided a scholarship I think it was about $200 dollars. I live with my elder sister, who was single in Cincinnati working as a housemaid. My sister left and I took over the apartment [and] my brother, who was single at that time, came after Jerome was closed. And then I got drafted, I was put into the enlisted reserve in September, took the oath and got a serial number. And then I was told to wait until I was notified for active duty.

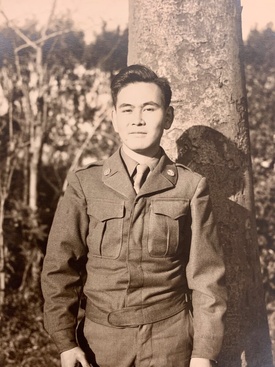

And I got a notice in December of ‘44 to report to Fort Hayes in Indiana. And from there I went to South Carolina for infantry training. And then the war with Germany was still on and then I came home on leave and met my mother. And then they sent me to Fort Meade, Maryland, for invocation to Europe but when I was there, the war ended in Germany. So I was there and they had looked up my records and said that I had gone to Japanese language school. So they didn’t tell me what they were going to do, but I get a notice later that, you will be going to MIS, the Military Language school in Minnesota. And I went there and they initially put me on a translators curriculum. I was supposed to look at Japanese kanji. Very difficult — 10,000 characters and I was supposed to memorize them because they wanted me, ultimately translate Japanese army orders. And when I was there during that training period in August, Hiroshima happened. And the war ended. And they immediately turned me away from this translator curriculum to conversational and I became an interpreter.

They needed a lot of military interpreters. So I boarded a ship in Seattle and spent 20 days on the boat and I got sick the moment the ship went to the ocean, and I was sick most of the time, and I swore I would never be put on a ship again. I did coming back, but [laughs].

It was pretty bad. And then had you already been speaking Japanese growing up with your mother?

Yeah with my mother. So I had conversation. I did go to Japanese language school when I was small. But I was a lousy student in Japanese, I used to play around more than I studied.

What was it like in Japan when you actually got to Tokyo? What did you end up doing over there in MIS?

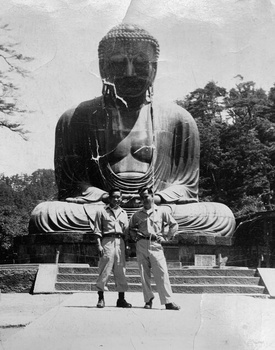

Well, after this 20 day ride on the troop ship, landed in Tokyo, Yokohama. I remember my first impression - my mother taught me how lovely the country was. How beautiful country and everything about Japanese. She never went back to Japan since she left. It was her promise to do so, she never did. So I got the impression that it was a very beautiful country, that people were good, so when this troopship landed at this port at night. The lights flicker around the wharf there, and they were starting to move around and everything and then the lights came on the ship and focused and those crowds of people skirting around a bit of food or whatever, being thrown overboard by the troops and the troopship. And I remember seeing an elderly man fighting over a piece of scrap or something like that. And this is my first glimpse of Japan — people fighting over food. They shipped me to Camp Zama, which is near Yokohama.

And that’s where the real shock of people who are starving came to the base because we had a mess in which we wiped out the food particles into a garbage can and it was full of garbage or waste. And the young kids and elderly people are sticking their hands in there and eating from that messy stuff there. And that was my first impression of these Japanese are all hungry animals waiting for food to come out. And that was the first impression. It was very negative in a sense. Later on I had trips to central Japan, to Ginza and all that. And there were sections of Ginza particularly, where buildings were empty because they were bombed-out. So there was devastation throughout. And the post office was located on the corner of Ginza, and I remember going in there buying things and other people outside were huddled around tanks of smoldering fire to keep themselves warm. Women didn't wear dresses they wore these pajama-like things.

It was sad. I was on a streetcar in Japan where there was a woman collapsed and was agonizing on the floor, grasping her stomach and in nearby Ueno, which was a railroad terminal. Every day there was two or three people that had died, they were carrying out the bodies from that. It was cold, there was a lack of food. The disparity between haves and have nots. But generally the whole city was depressed. People from the country would come and sell their food because they can get money for it from the city folks. I worked for the military police, 720 military police battalion in Hibiya Park, near the Imperial Palace. And I worked there all the rest of my time in Tokyo.

Were you doing conversational interpreting?

Well I would be at this reception desk and people will come up and ask me in Japanese this and this and talk to them in Japanese. On occasion, there was a pickup of woman streetwalkers. And what happened, this is a memorable thing. I was assigned to this group of Military Police that assembled the woman walking to a bathhouse close by. But they would be picked up and I would sit there and ask them what did, and where they were from and things like that to determine they were street walkers or just an occasional walk by. And I remember, I’d never forget this. One woman that I was interrogating was from Nihonmatsu which is in Fukushima-ken. That excited me because I hadn’t been up there, and as a consequence, I didn’t know what the reason for it is, but I let her go [laughs].

Did you meet your wife during this time in Japan?

No. But we have a funny story. Long after the war, she went to Ueno Park in Tokyo to a koto concert. I also went to Tokyo for NASA Ames for a scientific meeting and I happened to go to this concert. And it was pretty good. After we were married, I mentioned the fact that I’d been to this particular concert she goes, “Oh I went there, too!” We had never met before, we didn’t meet there. But it was coincidental that we’re at the same concert.

And your wife was from Japan?

She was from Japan. She was 33 when we were married. She came to this country on a travel visa not planning that, but we were sort of going along together. When her visa was up for renewal, we went to the immigration office, and she handed in her application. She came back smiling. I looked at it and it says, “Request denied. You will be deported in 30 days.” [laughs].

She didn’t know that’s what it said.

She didn’t know. So what happened was that I took that announcement and we went to the Japanese consulate and had a discussion. He said, “You should’ve come to me first. Now the only way she could stay is to be married to an American citizen.” So, there I was [laughs]. 41 years old and had all these complexities of a mother who is not exactly normal. But this person can speak Japanese so at least they can speak to each other. Subsequently I made the decision to propose, and subsequently everything worked out. We did go through these major hurdles where my mother was very possessive of her youngest unmarried son, who was her main supporter. My wife and my mother who initially had problems with each other developed a warm and happy relationship. During the final five years of my mother’s life, especially the period after she had a stroke. Mental peace, comfort, and gratitude.

So jumping ahead a few years, I always want to ask about the redress and the apology. When you received that, what was your feeling after getting it?

I was happy about it. I went around right away and bought a car [laughs]. So my my feeling is that it doesn’t at all compensate for the extreme damage — not to me so much as I think about my mother. I think that what the Isseis experienced of losing their place in the family unit has been predominant, and they’re responsible for the children and this kind of thing, completely overnight reversed where the children become a dominating and essential figure in their lives. And if you’re any human being, that’s a difficult thing to accommodate, a change of that thing.

In that case, it’s simply like the mental depression that my mother experienced and that she was responsible for the safety and welfare of her children during the Depression years after her husband died. That’s a lot of responsibility for a woman. To do that in a society that didn’t have a social welfare program as we have now. So I think the greatest harm and damage is - and it’s not fully expressed because the Issei parents are not of that type. They don’t openly admit to things like that, you know. And at my age, it’s my feeling that I understand exactly that my response is different from my parents, but I’m pretty open about it.

Misa Oyama [Jiro’s daughter]: But you went to the redress hearing, that changed the way you thought about the internment when you heard people talk about their experiences. You hadn’t thought about it before that.

Oh yeah. They had this redress thing [in San Francisco]. I went there and I didn’t have a chance to speak, but I listened to the experiences of the people that are affected by the evacuation in a real sense. Some lost their children and things like that. You can’t imagine working on a farm, slaving away, losing that overnight like that. No, you just can’t come to that — so the moneys involved, that’s happy but I think the recipient should use it extravagantly or anything else.

My mother, I remember in ‘65, I said they had passed a bill that Isseis could become citizens. And I went up to my mother and said, “Oh, Mom! You could become an American citizen!” She said, “What’s that?” She said. “It doesn’t help me now.” It didn’t help me at all. But it’s true. I understand it is nothing. It’s a paper switch, that doesn’t change the past. But it’s for the future, for good people that come in, that they would take our experience to contribute to how they might react and how they would respond particularly to other groups. This is why the Japanese Americans are at the forefront of opposing the antagonism and hatred that a lot of people feel towards the Arabs and other kinds of [people].

Yes, they know what it was like.

They know. So it’s those people that experience it and it’s the same with life itself. The older you get, the more understanding you should become. ‘Cause you got all these experiences. So anything new happen to you, you make it a point to understand pros and cons. Nothing is ever pure and simple when you have human organizations. And it’s always changing. My science background adds to that. I adapt with things that were ever changing, and life is that way. But when you’re older and you use your mind and your experience, you should come out to be pretty open-minded.

*This interview was made possible by the Japanese American Museum of San Jose and a grant from the California Civil Liberties Program. This article was originally published on Tessaku on March 1, 2020.

© 2020 Emiko Tsuchida