"Black Lives Matter." What do you think about this movement that is happening now? There are many different types of Japanese people living in America, including those with mixed black*, white, and Asian ancestry, as well as those who have married people of other races and ethnicities. Depending on their position and environment, I imagine that they may feel that "Black Lives Matter" is something that is relevant to them, or that it is something far removed from them.

As Japanese people, we are hardly ever exposed to racism in America that would put our lives in danger. With the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise in racism against Asians, we do encounter discriminatory words and actions, but fundamentally, it feels like law and order are what protect us. When and how did safety and fairness become something we take for granted? Looking back, we find that it has a lot to do with the history of black people in America.

From the beginning of immigration to the present, Japanese and Japanese-Americans have received help from black people, who are also people of color, but they have also been minority and subject to discrimination, and at times have discriminated against black people. However, at other times, they have overcome their racist consciousness and fostered friendships and solidarity. It is not easy for people with different cultures and customs to understand each other, but we live in such a complex society. By unraveling the history and learning how we got to where we are now, we may be able to draw a map of the future and see where we are going from here.

White towns, colored towns

Immigration from Japan to America began in earnest after the 1880s. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, banning immigration from China, and Japanese workers were sought after as an alternative labor force to Chinese workers. However, even though Japanese immigrants were needed as cheap labor, they were not welcomed by American society. Asians, including Japanese and Chinese, were denied membership in labor unions that were primarily made up of white people, and were forced to work under poor working conditions for low wages, and often had no or limited access to education and medical care.

Then in 1913, the "Alien Land Act" was enacted in California, which effectively prohibited "unnaturalized aliens" who could not naturalize in the United States from owning land (similar laws were subsequently enacted in 14 other states, including Oregon and Washington). At the time, the only people who were allowed to naturalize were "free white citizens, and free citizens born in Africa or of African descent." Japanese people who were neither white nor black could not become Americans, did not have the right to vote, and could not purchase real estate.

"In addition, many real estate records had racially restrictive covenants that limited how second-generation Japanese children, even those who were American by birth, could buy or rent in their own names," says Kristen Hayashi, curator and director of collections management at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

"Los Angeles developed in the early 20th century, but the social leaders of the time wanted to keep the city as a 'white town'. They established 'special alert districts' to prevent people of colour from getting loans from banks, and added racial restrictive clauses to real estate registers such as 'only white people can buy/live in', thereby restricting the areas where people of colour could live and preventing them from mixing into their white town. As a result, Japanese people lived in areas such as Little Tokyo and nearby Boyle Heights, alongside blacks, Mexicans, and Jews, who were also subject to discrimination."

Friendship beyond race and unity as people of color

In places where different cultures, languages, races, and ethnic groups coexist, tensions can arise due to prejudice and misunderstandings. "However," Kristen continues, "even if people have preconceived notions, by living close to each other and getting to know each other, they can sometimes realize that their prejudices were just that, and they can overcome their differences and find common ground. Examples of friendships that are born from this can be seen in our museum's Molly Wilson Murphy Collection."

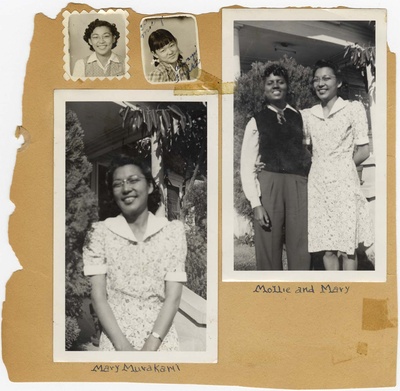

Molly, a black girl who lived in Boyle Heights, located southeast of Little Tokyo, developed friendships with the second-generation Japanese-Americans living in the neighborhood, and these friendships did not change even after the Japanese-Americans were sent to internment camps. Molly exchanged letters with them and sometimes sent them things that her friends in the camps needed. The Molly Wilson Murphy Collection is made up of the letters she received and photographs of her Japanese-American friends.

"Another example can be found in the Sakamoto-Sasano Collection: Chiyoko Sakamoto, a second-generation Japanese American who was the first Asian American woman to become a lawyer in California. Before the war, Chiyoko worked in Little Tokyo and lived in the Southwest District, where she met Hugh McBeth, a black lawyer."

After graduating from Harvard Law School, Hugh moved to Los Angeles in 1913 and filed various lawsuits against racial discrimination, and was one of the people who spoke out against the exclusion the Japanese American community faced. He filed a lawsuit arguing that "internment based on race was unconstitutional and discriminatory," and unfortunately lost the case. However, he continued to send letters of support to the Army's War Relocation Administration, which had jurisdiction over the internment camps, and to President Roosevelt at the time, defending Japanese Americans.

"During the war, Chiyoko was sent to the Amache internment camp in Colorado, where she provided legal advice to the prisoners. After leaving the camp and returning to Los Angeles, she struggled to find work due to racial discrimination. That's when Hugh welcomed her into his office as a colleague."

Like Hugh, black lawyer and journalist Laurent Miller also protested the internment of Japanese Americans and fought for the civil rights of minorities in general. Charlotta Bass, then editor-in-chief of The California Eagle, a black newspaper that Laurent later became the owner of, also published many critical articles claiming that the internment of Japanese Americans was a violation of civil rights. In order to show solidarity with Japanese Americans, the paper also stopped using the word "Jap," a derogatory term for Japanese people and Japanese that was used by many media outlets at the time.

Another black newspaper, The Los Angeles Tribune, took a newspaper policy stance against incarceration shortly after Executive Order 9066 was issued, which led to the incarceration. Elna Harris, a reporter and activist at the paper, wrote two years later, "This problem is racial, and it can happen to anyone who is perceived by appearance as a 'person of color.'"

Kristen says, "What happened to the Japanese Americans was the same as the discrimination that black people have experienced. There's a scene in Chester Himes' novel, 'If He Hollers Let Him Go,' in which a young black man working at a shipyard in Los Angeles is unable to sleep out of fear that he would suddenly be arrested and taken away like the Japanese Americans. It wasn't surprising that this could have happened to them at any time. It wasn't easy for black people who had suffered from racism themselves to stand up for the Japanese Americans, but Hugh, Laurent and others spoke out anyway."

*Note: In the United States, the term "African American" is often used, but there is a growing movement to include black people of other descent as well, and to use the proper noun "Black" with a capital B instead of the adjective "black" with a lowercase letter to indicate color. Based on this, we use "Kurojin" as the translation of "Black" here.

*This article is reprinted from The Lighthouse (Los Angeles edition, August 1, 2020; San Diego edition, August 2020; Seattle/Portland edition, August issue).

© 2020 Masako Miki / Lighthouse