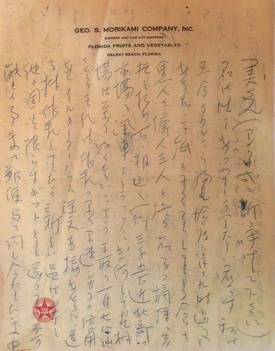

Morikami Sukeji, who traveled to America as a member of the Yamato Colony in South Florida and remained there alone until the end of his life after the colony was disbanded, continued to send a huge number of letters to his sister-in-law, Okamoto Mitsue, who had lost her husband (Sukeji's younger brother), and her family after the war. Up until now, we have been tracing Sukeji's life by introducing these letters, but these letters had been kept for many years by Mitsue's second daughter, Mihama Akiko, Sukeji's niece. We asked Akiko, who lives in Kizugawa City, Kyoto Prefecture, to read the letters again and asked her about her uncle Sukeji.

* * * * *

(Only by letter, without ever meeting in person)

--It seems that you received a lot of letters from Sukei-san from the 1950s onwards, after the war. It's amazing that you kept this one instead of throwing it away.

Mitsuhama: They weren't just for me. They first came to my mother's house, and then many of them came to my sister and me. Now that my mother and sister are both gone, I've gathered them all together and kept them.

When I reread the letters from my uncle (Sukeji), he wrote that he would return any letters we sent him, but he never did so. I wonder what happened to him after he passed away.

-- That's right. If Suketsugu had returned to the Okamoto family, the interactions between them would have been a little clearer. By the way, even though there were so many interactions over a period of about 30 years, Suketsugu never actually met the Okamoto family members. Furthermore, Suketsugu also acted as Mitsue's husband and as a father figure to Akiko and the others.

Mitsuhama: That's right. At one point, my uncle said he wanted to adopt my sister, and someone came to tell him, but I never actually met him. I never even spoke to him on the phone. After my uncle passed away, my brother went to Florida twice and my sister went once.

Gratitude to America, an amazing person

-- I think that the letter gave us a new insight into Sukeji's way of life and what kind of lifestyle he lived. What impressed you the most?

Mihama: There were many things in the letters that came to my mother that I didn't know. There were things like "I'll send you the money you requested," and it made me realize just how much they'd taken care of me. Also, he'd come close to death so many times, gotten sick and injured, and yet he'd managed to survive. He remained in the Yamato Colony until the very end, and expressed his gratitude by saying, "It's all thanks to America that we've become like this," and I thought he was an incredible person.

Also, the reason he went to America was because he couldn't marry his first love, but I learned that he had always thought about that person. It's hard to imagine in this day and age.

-- I imagine you had the desire to return to Japan and be recognized by your first love if you were successful in America. But you never returned to Japan. You kept saying you would return, but it never happened. Why was that?

Mihama: I wonder why. I think it was because I thought that once I returned to Japan, I would never be able to come back.

Difficult and outspoken personality

--Looking at the letters, we can see that he often expresses anger at Japanese customs, the way Mihama and his family lived and thought, etc. What kind of personality did Sukeji have?

Mitsuhama: He was very strict, and when he helped me with my school expenses, he asked me to report how he spent the money, so I also kept a household ledger and sent it to him. He had a difficult side, and even if I told him things that I thought were good, he would get angry if they bothered him. But after a while, he would often go back to his old ways.

-- Although you only communicate through letters, you're like family.

Mihama: That's just how families are, isn't it? Even if they fight, they quickly go back to normal. Also, I thought that my uncle's frank way of speaking was Americanized.

Who will guard his grave?

-- Sukeji's grave is in a corner of the grounds of the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens in Florida, and his name is also engraved on the grave of the Morikami family in your hometown of Miyazu, Kyoto Prefecture. However, in addition to that, Akiko and the other members of the Okamoto family built a grave in Shiga Prefecture.

Mitsuhama: In the letter, my uncle wrote that he had already arranged for a grave here and that it had already been prepared in America, but it seems that this was not the case. Perhaps he passed away before it could be prepared. I brought back some of his ashes and placed them in his grave for my uncle who had been so kind to me. However, I wonder if I will be able to look after the grave in the future. I am already 80 years old, so I am a little worried about what will happen after that, although it will be fine for my children's generation.

(Some titles omitted)

© 2020 Ryusuke Kawai