Chiyoko Sakamoto was an innovator in her day, and a trailblazer for the Nikkei community. Sakamoto was the first Japanese American female lawyer in California, and throughout her career, she uplifted the Nikkei community in ways that still have ramifications today. In this article, I will outline my research process, outline my goals, and highlight what I learned by working on this project.

As a Nikkei Community Internship intern, I was assigned to work with the Japanese American Bar Association and the Japanese American National Museum. Chiyoko Sakamoto was one of the founders of the Japanese American Bar Association and the Japanese American National Museum has her family’s collection in their permanent collections. I was assigned this project in order to create an article that would further document Sakamoto’s legacy and impact on the Nikkei community.

Chiyoko Sakamoto was born in 1912 in Los Angeles, California. However, her sister Taye, was born in Japan. Growing up, Sakamoto had more civil and political rights because she was a U.S. citizen, whereas her family and her sister were considered aliens. It was not until 1952 that her sister Taye became a naturalized citizen.

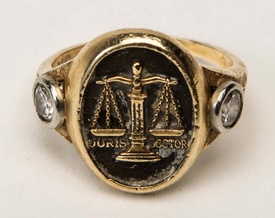

Having the opportunities of an American citizen, Sakamoto decided to go to law school, and enrolled at the American University Washington College of Law in Los Angeles. While attending law school, she worked as a secretary during the day, and attended her law classes at night. She was admitted to practice law in 1938, immediately after graduating from law school.

However, being a Japanese American woman, it was not easy for Sakamoto to find a job as a lawyer, but eventually she found a job working as a legal assistant.

Even though it seemed that Sakamoto’s career was about to blossom, this initial success was short lived. In 1942, at the start of World War II, Sakamoto was forced to move out of Los Angeles and was imprisoned at the Granada concentration camp in Colorado. Once Japanese Americans were allowed to leave the camps in 1947, Sakamoto began her search again to find work as an attorney.

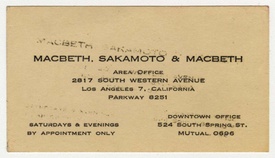

Sakamoto’s job search proved to be tougher than her first time. While struggling to find employment, she met Hugh E. Macbeth, an African American attorney. Macbeth was a prominent supporter of the Japanese Americans during World War II, and believed that the incarceration of the Japanese Americans was completely unconstitutional. Macbeth had previously taken up landmark cases such as the People v. Oyama, People v. Hirose, and even challenged the Alien Land Act of 1913. When Macbeth heard about Sakamoto’s search for employment, he hired her as an associate at his Los Angeles law firm.

Given this opportunity, Sakamoto thrived. She was able to advance in her career and after Hugh Macbeth passed, she started her own firm in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo. Unfortunately, in 1994 she passed away, but her legacy will never be forgotten. Over her career, she did more than just practice law. Sakamoto was dedicated to creating opportunities for others and growing her community around her. For example, not only did she co-found the Japanese American Bar Association, she was also one of the co-founders of the California Women’s Bar.1

When I began this project, I did not know who Chiyoko Sakamoto was. After learning even these basic facts about her life story, I had such a deep appreciation of the work that she did. Being the only Japanese American female attorney of her time, she did not have equal opportunities compared to other attorneys who were not Japanese American and female. The fact that she continued to persevere, never gave up, and achieved what she did made me grateful for what I have. By founding the Japanese American Bar Association, she has opened the door to equal opportunity for me as a Japanese American to study law and to be hired as an attorney. With this newfound appreciation, I was inspired to learn more about her, and to dive deeper into her impact on the community.

Before I did any more research, I outlined two main goals that I wanted to pursue through this project. First, I wanted to learn about her impact on present attorneys and others that are involved in the Nikkei community. Second, I wanted to know what drove Sakamoto, what inspired her to be an innovator and to found the California Women's Bar and Japanese American Bar Association, and what motivated her to persevere through all the obstacles that she faced in her life.

When I began researching Sakamoto’s impact on attorneys who are currently involved in the Nikkei community, I discovered that Kira Teshima, the current president-elect of the Japanese American Bar Association, was heavily influenced by Sakamoto’s work. Teshima said, “To think that California’s first Japanese American female lawyer was a member of JABA is just incredible” and follows this statement by saying that Sakamoto, “paved the way for future women like me to build a career in the legal field.” Teshima explained that she has the utmost respect for Sakamoto, and is grateful for Sakamoto’s work, which created a foundation for lawyers like her.

Other judges and justices I spoke to were inspired by Sakamoto’s work. Justice Katherine Doi Todd, the first female Asian American judge in the U.S., and Judge Ernest Hiroshige, who was also one of the founding members of the Japanese American Bar Association, were both influenced by Sakamoto. Justice Todd remembers Sakamoto at some of the first few meetings of JABA and described her as “wonderful” and “elegant.”2 Judge Hiroshige had a similar perspective about Sakamoto. Although he did not have any specific stories about Sakamoto, he recalled that Sakamoto “always had a very positive reputation as an attorney.”

Although Sakamoto was an attorney, her influence goes well beyond the field of law. Many other impactful leaders in the Nikkei community have been inspired by Sakamoto’s work. One of these leaders is Kristen Hayashi, the Director of Collections Management and Access at JANM. Hayashi has written articles about Sakamoto, for both the Discover Nikkei website and the Densho website. Hayashi has the utmost respect for Sakamoto and says, “Becoming the first Asian American female attorney in California, after passing the state bar exam in 1938, elevates Chiyoko Sakamoto's significance. Yet, her lasting legacy far exceeds this accolade. It is extraordinary to think about how Chiyoko Sakamoto navigated discriminatory barriers that continued to severely obstruct the social mobility of people of color as well as women within U.S. society, in order to achieve her career.” Hayashi says that Sakamoto’s influence on her was not just because she was the first Asian American female attorney, it was because of the work that Sakamoto did to help others and to change social norms. Seeing that her work truly inspired others, I wanted to know more about what motivated Sakamoto to create equal opportunities for the community.

After I researched Sakamoto's impact on the Nikkei community, I began researching her motivations and what inspired her innovative way of thinking. I hoped by doing so, I could provide a more personal connection with Sakamoto in this article. However, trying to find people that had a personal relationship with Sakamoto proved to be difficult. After contacting as many individuals as I could through the help of JABA and JANM, I was not able to find anyone who knew Sakamoto personally and that could speak in detail about her motivations and way of thinking. Although I was not able to find anyone to reference, it taught me a valuable lesson about the accessibility of resources. Oftentimes it is easy to think that resources will be available and found easily. However, it’s often not, and researching this project has given me a new found respect for those who continually research and document history, so that the community will have resources for the future.

Overall, writing and researching this article has helped me grow in so many ways. First of all, learning about Sakamoto made me so grateful for all of the opportunities that I have today. I hope that in my career, I can make a difference as she did, and continue to create opportunities for others as she has created them for me. In addition, it made me extremely grateful for the resources and history that have been documented about Japanese Americans. There are so many individuals, in the Japanese American community and beyond, whose stories and experiences are not documented. Not many communities have organizations like JABA and JANM that document their community's history, so I am grateful that the Nikkei communities even have these organizations. Through all of the emails, database searches, and conversations, I was able to gain experience in what it takes to do in-depth research. Although I fell short in achieving my second goal, I now have the skills to carry out meaningful and detailed research projects. Overall, I was able to learn so much about Sakamoto and the community, and this experience was extremely eye opening in so many ways.

I will forever cherish this opportunity to learn about Chiyoko Sakamoto and it has been such an honor to write about her. Sakamoto's life has inspired me to work with determination and has given a deeper purpose to my career. I hope that in my work, I can leave a lasting impact on the Japanese American community just as Chiyoko Sakamoto did, and to be a force for good in all society.

Notes:

1. Jonathan Watson, “Legacy of americaN female Attoneys,” (rev. 2016), Solano Library.

2. “The Other Two JA Women Lawyers in Los Angeles-Chiyoko Sakamoto and Madge Watai.” Interview with Kathryn Doi Todd. Discover Nikkei.

*This is one of the projects completed by The Nikkei Community Internship (NCI) Program intern each summer, which the Japanese American Bar Association and the Japanese American National Museum have co-hosted.

© 2020 Matthew Saito