One of my fondest memories is of the annual mochi making party that was held at our house in the week after Christmas and before New Year's Day. My Kurosu second cousins, the grandchildren of Jichan’s elder brother, Shinsaku, would come to our house in South Park to make mochi. The sweet mochi rice would have been pre-washed and steamed over pipes from the steam boiler which heated our greenhouses adjacent to our home.

My Kurosu cousins recently told me that they also made mochi at their house, steaming the rice in their greenhouses and using the same mochi making equipment we did; only their steaming containers were rectangular and ours were circular. Perhaps the Kurosu family started making mochi at their own place after we stopped having mochi making parties at our home. At some point, one of the family greenhouse cash crops changed to Easter Lilly plants. The week between Christmas Day and New Year’s Day was often the week in which the Easter Lily bulbs were moved from their dirt covered, resting places in beds outdoors, into the greenhouses. The timing for moving the lily plants into the greenhouses depended on the date of Easter for any given year. I remember Jichan purchased one of the early mochi-making machines from Japan around the time that we started the Easter lily production, probably because the family didn’t have time to pound sweet rice the traditional way anymore.

Our Japanese friend, Yasuyo Komatsu, remembers her family using equipment identical to ours when she was a child. I remember at our house when we made mochi, the hot-steamed rice would be placed in the base of a large, hand-carved, wooden mortar or usu and then pounded with a wooden hammer (pestle) or kine. In between downswings of the hammer, Bachan Araki would quickly turn the hot rice with a shamoji and throw some water on it, moving out of the way just in time to avoid being hit with the hammer.

As the pounded mochi cooled, Mother, Father, my younger sister Louise, Mrs. Kurosu and her husband, my second cousins, and I would shape the pounded rice into smooth cakes, rolling them in katakuriko, or potato starch. Sometimes the pounded rice would be shaped around anko, or sweetened azuki bean paste balls. My favorite kind of mochi was an “inside out” version of anko-mochi called ohagi, with a ball of steamed whole-grains of sweet rice surrounded by sweetened azuki beans. Once we finished making all the mochi, we’d have a meal in the house. One wonderful year, I remember playing Chinese checkers and other games we’d got as Christmas presents with my Kurosu cousins.

The mochi was left to dry in wooden boxes in the boiler house or our basement, and we would enjoy them on New Year’s Day in ozoni. I don’t recall Mother using miso (fermented mashed soybean) paste in the soup, Fukui-ken style, as described to me by Yasuyo Komatsu. Mom’s soup was a clear broth, flavored with grated daikon, grated carrots, and perhaps some spinach or bok choy or shitake. Perhaps this is a more southern Japan style ozoni broth, since Mother was from Yamaguchi-ken. I still enjoy ozoni on New Year’s Day, but I make the broth using prepared dashi and chicken stock or chicken bone broth.

Every year, my dear Japanese American friends in Tucson, Terry and Susie Matsunaga, present me with beautiful plain and yomogi mochi cakes. Yomogi mochi is made by working pounded fresh Japanese mugwort greens, or yomogi, into the freshly made mochi. The yomogi greens give a lovely, delicate flavor and soft green color to the mochi. The yomogi mochi cakes are especially moist and tender. The Matsunagas know I savor yomogi mochi in my ozoni. They prepare their mochi in a mochi making machine from Japan. The Matsunagas tell me that before the machines were developed, they and family members in California pounded their mochi in cement weighted wooden barrels.

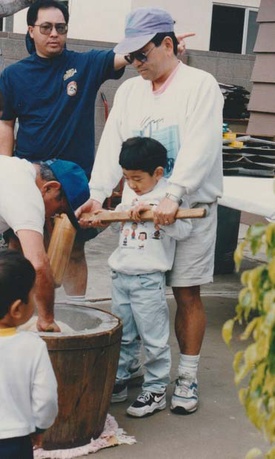

The Matsunagas have kindly provided photographs taken in 1994 by Susie’s cousin Leslie Sakioka of Christmas time family mochi making festivities at the home of Susie’s uncle, Shizuo Sakioka. Participants are using an usu, made from a sake barrel, and a kine of orange tree wood, both made by a grandfather of the Sakioka family around 1920. Including children and the whole family in mochi-making keeps old Japanese traditions alive in America.

Apparently kine and usu made of other materials beyond solid pieces of wood have been used by Japanese Americans, just as in different parts of Japan, materials other than wood are used for making the mortar and pestle. I have seen photographs of beautiful stone usu by googling “different kinds of kine and usu in Japan.”

This year, the Matsunagas also gave me a huge and very sweet daikon root, which I cooked and enjoyed very much. As a child, I liked grated raw daikon but hated the smell of cooked daikon, which was a dish that Jichan and Bachan (who lived in Tokyo for much of her life) loved. I have become more like Jichan and Bachan in my old age and enjoy cooked daikon, especially in Chinese turnip cake, as well raw daikon in dishes like namasu. We did not eat our mochi Fukui-style, with grated fresh daikon or daikon oroshi, but rather we oven broiled or fried our mochi with a sauce of shoyu and sugar on top. A Chinese friend who has lived in Taiwan and Japan has fond memories of eating fresh mochi with kinako (powdered soy bean flour) and sugar.

Friends, especially female friends, of all nationalities seem to love soft, sweet mochi flour (mochiko) based sweets. It seems that all Asian nations have delicious recipes for pastries that use mochiko. I have treasured recipes—gleaned from Hawaiian cookbooks —for chocolate mochi and pumpkin mochi. Everything, including mochi making, is very different today but enjoying ozoni and mochi based sweets remains the same.

© 2020 Susan Yamamura