What is the state of the school today? What is the enrolment? What is the makeup of students e.g., from Japan, descendants of the first wave of immigrants, non-Japanese? Number of teachers?

Our organization today reflects our 114 year evolution to sustainability. We have three operational divisions: child care division (daycare and immersion preschool - 135 children); Saturday and adult weeknights; language division: adults - 300+; children 6-18 - 250; community programming (heritage education and outreach and community rentals). When I was attending Japanese school as a kid in the 1980s, I went Tuesdays and Thursdays after school and all my classmates had both parents who were Japanese Canadian. Now the tables are turned. Eighty-five percent of students have perhaps a small percentage of Japanese ancestry, but the majority do not. Most children speak a minimum of three languages or more. Being a multicultural citizen is now the norm and majority.

Can you talk a bit about your personal connection to the school? Did you go there as a kid? What does being JC mean to you?

My mother attended the school in grade 1 when the war broke out. My paternal grandfather was on the reestablishment committee to get the school’s building back after the Internment. He got my father who was a young man to help with all the cleaning, repairing and painting so they could reopen the school. My parents were community leaders at the school for decades. My mother was the Womens’ Auxiliary chair that did all the food fundraising and my father was the Y2K Committee chair that built the 5-storey addition. I graduated elementary level in the ‘80s and attended the pre-renos building every Tuesday and Thursday afterschool. While I hated going to Japanese school as a kid, when I grew up and I was grateful to my parents who stuck it out and kept taking us. While I thought I didn’t learn anything, because I was exposed at a young age, and could understand Japanese, I was able to advance quickly at UBC and go to grad school in Tokyo.

Can we expand on the value of Japanese in your life? What did you study in grad school in Tokyo? Was this in Japanese?

I did my master’s in Sociology at Sophia University in Tokyo. It has its roots as a Jesuit based International University, very well-known internationally. Yes, I did the course in both Japanese and English, and I also was a member of the Jochi Shimbun editorial staff. My aim was to be able to communicate in written Japanese as well, so I joined the student newspaper and did some amazing interviews, such as the president of Sumitomo Japan, etc.

What is the value of Japanese in your daily life now? Do you speak with your family in Japanese? Your parents? Siblings? Friends?

Well, I serve on the board and the Vancouver Japanese Language School & Hall, and so need to communicate in both languages when I volunteer, be that being the editor of our E-newsletter, reviewing communications, or just hanging out with Japanese staff and parents. Yes, our mother, who is Nisei, 87, feels more comfortable speaking Japanese now. It was her first language before she attended public school. She has dementia, so her conscious mind (meaning English) is less strong, as she lives in her subconscious most of the time. She feels at home speaking inaka Japanese to us and teaching the care home staff the Japanese swear words!

Can we have a JC community without a connection with the Japanese language and culture?

Yes, one university student asked me, who is the Japanese Canadian community? Good question. I replied it is no longer DNA defined (meaning you have to have Japanese genes). The community is defined by our values, meaning loving and being connected to Japanese language and culture. This is illustrated by our current student population. Forty percent of our students are K-12, and possibly have an ancestral connection. Sixty percent of our student body are adult continuing education students, the majority of whom do not have any connection to Japanese ethnicity.

The second reason is also embracing and learning the lessons from Japanese Canadian history. The lessons of racism, of intolerance, fear and also community resilience are all lessons anyone can benefit from learning. They are lessons of humanity and strong citizenship. A community is about belonging and sharing common values. Having a shared history definitely helps and it often is a seed leading to learning more about Japanese language and culture. But it is not a necessity.

What in fact is the value of learning Japanese in 2020? Are the kids today making the same complaints as those of earlier generations about being forced to learn?

The value of learning Japanese is that it is a window for strengthening intercultural communication, culture, and connection. Language embeds different cultural values and customs. Like Japanese food for example, knowing what sushi is enables us to order sushi at a restaurant. Being multilingual lifts the lens of our own cultural belief system, and in this global world, that is important to be conscious of.

Yes, of course, kids complain about going to Japanese school, like we did when we were kids. But when I look at the content and tools of their learning, it is way more fun. And it’s much broader. We live in a global society, so it’s very different from when I was growing up and I was a visible minority and attending Japanese school made me feel different. Today, at our school, on the train, at public school, if you’re not multilingual, you’re a minority. At minimum, most children who learn Japanese at our school speak three languages. So it’s a natural and majority multilingual environment. And parents recognize the value of not just learning Japanese, but being a part of a larger community organization with a resilient history of community service and consciousness gives their kids much valued societal skills and consciousness. Community education, as we’re all learning during the COVID-19 era, is critical to understanding the collective good, and not living in a self-contained bubble.

What is the culture at the school like today?

Today, the environment at the school is very different than when I was going to school as a kid. It is open, diverse, and multicultural. I was the only Asian kid in an all Caucasian class growing up on the west side of Vancouver. So I had a distinct feeling of being a visible minority. None of my friends went to Japanese school or went to the Buddhist temple, so I was very different and experienced underground racism. Today, the curriculum content is much improved, there is highschool level, and now childcare, community programs, and being multicultural is the norm, not the minority. Culture and language is openly valued in a way that has changed a lot, and the Japanese Canadian community is no longer ethnically defined by genetics. It is defined by whether or not you love Japanese culture.

Are there commonalities of learners and educators over the generations that you can point out?

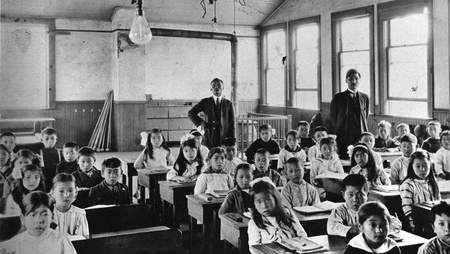

From the writings of Japanese Canadian community leaders, educators and pioneers to Canada, like those who lived before WWII, they were conscious of the institutional racist environment and the difficulties for their kids and families to build successful lives. But they did not give up. The adversity forced the community to dig deep into understanding what was their new cultural identity, that it was changing, and to learn how to integrate with Canadian society in addition to embracing their ancestral culture and identity. They were strategic thinkers, philosophers, and hardworking. They did not give-up, but found ways to be creative, work within the system to improve the system and build a stronger multicultural Canada. This together with discipline, hard work and strategic thinking with the collective goal of improving everyone’s life was a key aspiration which they continued to work at.

This strength of community resilience shone through again during the Internment period and after the war during rebuilding. I feel we have inherited this legacy: to be adaptable to change, continue our commitment to sustainability, equality, and resilience and celebration of our integrated cultural identity, which is evolving as well.

Do any teachers from your time at the school stand out?

Yes, our Principal Sato, who is an amazing community leader as well as educator.

Have you maintained friendships with classmates from those days?

Yes, one of my former classmates is a fellow board member. Many of our Japanese school friends are like cousins. We don’t keep regularly in touch, but being like family members, if they needed help, we would be there.

How do you self identify yourself ethnically these days as a JC?

First and foremost, I identify myself as a human being, and do not see myself as ethnically defined. I am a global citizen and at the national level, a Canadian citizen with Japanese ancestry and deep cultural and historic connections with the history of Japanese Canadians.

What is the place of the school in the greater Vancouver community today? Would you say that it is a hub of the JC community there? Do you know how many Japanese schools exist in BC today?

Today, the Japanese Hall has the largest Japanese language student population amongst the 15 or so Japanese language schools in Metro Vancouver. It is an educational and community hub, and now with National Historic Site designation, will become a heritage education anchor to tell the story of our organization as a prism for telling the Japanese Canadian story. Thus, we are a leader organization in spearheading the celebration of Japanese language and culture and Japanese Canadian history.

Can you please list some of the other initiatives that the school has been involved with e.g., the Heritage Sign project?

As one of the leader community organizations, to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Internment in 2017, we partnered with many Japanese Canadian organizations and the provincial government to create and install eight Interpretive and three Stop-of-Interest signs at the actual Internment and Roadcamp sites in the BC Interior. The next big project on the horizon is our Interpretive Centre Renovation Project, which will tell the story of our organization and of Historic Powell Street and educate the lesson of our history. This includes the creation of our archives to house our historic treasures and a digital archive. This involves Historic Walking Tours, such as the Tenement Museum does in NYC, and student education field trips.

Moving forward then, what do you hope will be the role of the school for generations to come?

My hope for the future is sustainability to nurture and transform the legacy of community resilience and spirit from the past century for the next 100 years. We are here today because of community, and because of our ability to adapt and respond to changing internal and external forces. This future vision involves becoming an education and community hub for activating and honouring the history of Powell Street/Japantown, continuing our legacy of Japanese cultural education and building the strength of community as it continues to evolve and redefine itself in the Downtown Eastside.

Any final thoughts?

As victims of displacement and racism ourselves, it’s important to teach and share these lessons with future generations to avoid history repeating itself. Come down to visit us in the heart of the Downtown Eastside, go on a historic walking tour, reconnect with the past, with culture and language and with the local community. The legacy of our ancestors and the story of the School is one of community resilience and strength to overcome and rise above adversity without becoming victim to it. We are privileged to build on this legacy with compassion and vision in today’s world to effect change for a better tomorrow.

For more information, visit their website at www.vjls-jh.com.

© 2020 Norm Ibuki