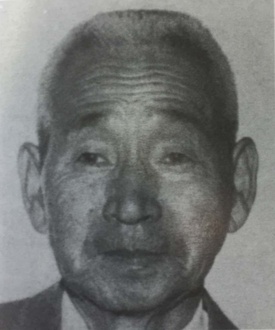

Hisajiro Inouye was born in Gotsu, Shimane, Japan, on January 8, 1897, to parents Kennosuke and Yome Inouye. He was married to Takeyo Inouye at 18 years of age, and the next year he and his family moved to America. They arrived in 1916, and settled in San Jose, along Gish Road, becoming tenant farmers.

The family settled on land owned by John Della Maggiore, an Italian immigrant from Firenza (Florence), Italy, who helped him farm along with several other Japanese American families. Hisajiro was very active in the Japanese community, specifically with the San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin, of which he was a founding father. He fathered seven children: his first daughter Umeyo, raised in Japan by relatives, Kyuji, who died as a child from dysentery, his second daughter Marcella (married name Kumamoto), Raymond, Betty Kiyoko (married name Ouchida), Gordon, and Wright Masayuki. They lived on the farm next door to his sister, Elsie Inouye, who was a nurse and worked at the Alum Rock Sanitarium.

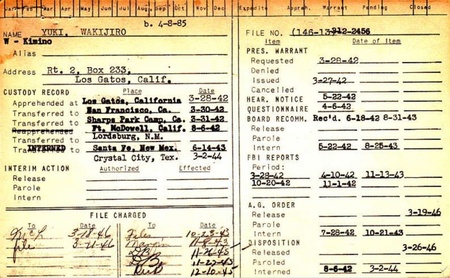

Hisajiro was arrested at his home on April 28, 1942, transferred to San Francisco and then Sharp Park near Pacifica, and was questioned in the Post Office building at Seventh and Mission Streets in San Francisco. The Alien Enemy Hearing Board No. 3 unanimously recommended that Hisajiro be interned, stating, “The subject was extremely evasive. His answers were generally untruthful and in many instances intentionally not responsive to the question asked.” It gave no examples of this evasiveness in its opinion.

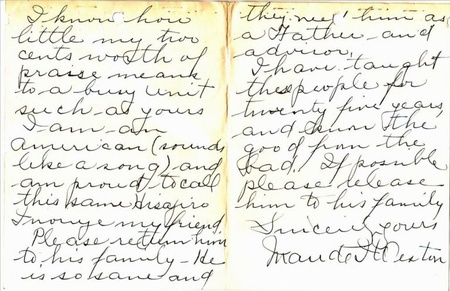

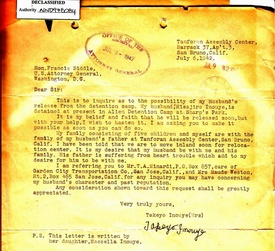

Hisajiro was taken to Fort McDowell on Angel Island on August 14, then was transported to Lordsburg, New Mexico, then to Santa Fe on June 14, 1943. Meanwhile, his family was taken to the Tanforan Assembly Center, and then interned in Gila, Arizona, a stark contrast to the temperate California. While he was interned, the family stored their equipment in their neighbor Maud Weston’s barn, and whatever they didn’t, she helped them sell. In a letter he wrote in gratitude for her kindness, he states “We are [feeling] the bitter coldness over here not like in San Jose, where we used to be.” He also thanks her for the letters and gifts she had been sending to his wife and children in Gila. Weston also wrote a letter in support of Hisajiro to the Department of Justice. An excerpt follows.

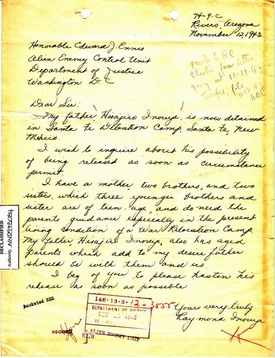

Hisajiro’s file currently stored in the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, reveals that during 1942-3, many of his family and friends wrote letters to Edward Ennis, director of the Alien Enemy Control Unit of the Department of Justice. The letters indicated that Hisajiro’s father, who was incarcerated with them, was suffering from heart trouble. Letter writers included wife Takeyo, daughter Marcella, sister Elsie, one from all the children, and Private Tadao L. Kodama, who said Inouye was his guardian before he was inducted. Kodama was a member of the all-Japanese 442nd Regiment, 2nd Battalion H Company and said, “I have observed very closely that Mr. Inouye has never attempted, committed nor suspected any offense to jeopardize the Government. For these reasons & for his family sake, I appeal to have Mr. H. Inouye released from Lordsburg, New Mexico & transfer to join his family in War Relocation Camp in Gila Rivers [sic], Arizona. I’m willing to take any responsibilities toward his conduct upon his release.”

The letters seemed to finally have an effect, and on November 17, 1943, Inouye was paroled from the Santa Fe camp run by the Department of Justice to rejoin his family in Gila River, Arizona. He was not allowed to travel, however, until December 10.

After the family was released, on April 19th, 1944, they returned to John Della Maggiore’s farm on Gish, but there wasn’t sufficient housing for them anymore. In order to combat the housing issue faced by Hisajiro and the other Japanese tenants on his farm, Maggiore decided to build them houses from spare lumber. Hisajiro and another tenant, Roy Sakae, helped him build. Maggiore states “Housing is desperate, so we are building temporary shelter for our returning Japanese employees.” However, many Japanese didn’t have kind employers like Maggiore, and they faced the looming problem of homelessness until they could find a place to stay, as they had lost all their money and assets before the war.

After they had settled down, they bought eight acres of land on Lundy Road where they cultivated strawberries and green onions. Right after the war, they were visited by Joe Nikei, a family friend, who was a veteran from Hawaii.

Elsie, Hisajiro’s sister, lived next door on Lundy Avenue. In 1984, she received recognition for being the first Japanese American employed by the county, and being the first county worker identified as one of many forced into internment camps. County Board Chairwoman Zoe Lofgren presented her with a plaque, commemorating her career and the injustice done to her, saying “This doesn’t make it right what happened, but at least it’s a recognition of what happened.” She also received $5,000 in reparations from the board.

During the war, Hisajiro’s older son, Raymond, enlisted in the military after turning 18 and getting released from camp. At this time, he was in basic training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. He eventually went on to become a Military Intelligence Service veteran, after attending the MIS Language School at the Monterey Presidio. Along with other Nisei veterans, he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2010 for their achievements and contributions.

After the war, Hisajiro’s son Gordon was quoted as he continued farming. He is described as someone who “knows a beanplant from a noxious weed,” and gets along with his Caucasian playmates. He states, “The kids are all swell to us.”

Hisajiro returned to his active position at the San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin, eventually becoming president from 1953 – 1955, and in 1959. He died on March 21, 1971, at the age of 74.

Sources:

Family information and photographs: Sandy Imai, granddaughter of Hisajiro Inouye, January 2020.

Historic documents: The National Archives at College Park, Maryland. Special thanks to Adriana Marroquin for their retrieval.

*This article was originally published on Immigrant Voices. For more information about the Japanese immigrant experience on the island during World War II, visit the history section of the AIISF website, which has a link to a database of over 600 people, and to read individual stories about those detained on Angel Island during World War II, read these stories from their Immigrant Voices website. Original funding for this project was supplied by the Japanese American Confinement Sites (JACS) program of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

© 2020 Marissa Shoji