As with other tragic chapters in United States history, the incarceration of Japanese Americans has had a lasting legacy on American culture. While the history of race relations in the American South has traditionally focused on black-white relations and the legacies of Jim Crow, a parallel field examining the experience of Asian Americans in the Deep South has emerged, featuring the work of such authors as Greg Robinson, John Howard, Moon-Ho Jung, Stephanie Hinnershitz, and Lucy M. Cohen. In places scattered throughout the American South, the incarceration left an imprint on the social landscape: the area surrounding the Rohwer and Jerome Concentration Camps in Arkansas, and resettlement of Japanese Americans there and in neighboring states; the Issei internees at Crystal City and the other camps in Texas and at Camp Livingston, Louisiana; and the training of the Nisei soldiers of the 442nd RCT/100th Battalion at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. The presence of Japanese Americans in public spaces posed a new challenge to the racial order of Jim Crow South, while for Japanese Americans it revealed another dimension of the hypocrisy surrounding American racism.

A number of white Southern leaders publicly supported the initial incarceration—Congressman John Rankin of Mississippi demanded on the floor of the House the deportation of all individuals of Japanese ancestry, while Senator Robert Reynolds of North Carolina publicly spread unfounded rumors of Japanese American sabotage at Pearl Harbor. Yet ultimately a handful of Southerners of different backgrounds offered important support. Mississippi businessman philanthropist Earl Finch, the “godfather” of the 442nd, was the best known, but there were others. Missouri-born Langston Hughes sounded off repeatedly against Executive Order 9066 in his Chicago Defender newspaper column. Poet John Gould Fletcher visited the camps and advocated for poets such as Kenneth Yasuda. One notable figure was journalist Hodding Carter II, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his advocacy on behalf of Japanese Americans. Carter’s work was unique thanks to his interactions with Japanese Americans in the South and his writing about the camps as part of a broader discussion of racism within the United States.

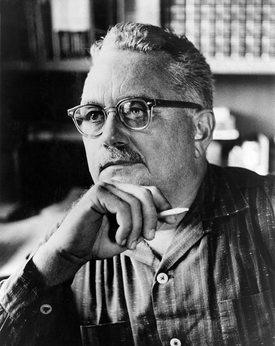

Born in Hammond, Louisiana to a Louisiana political family in 1907, Carter started his early adult life as a white supremacist and conformist to the Southern racial hierarchy. In her book Hodding Carter: The Reconstruction of a Racist, Ann Waldron noted how Carter’s attitudes towards racism evolved following his education at Bowdoin College and Columbia University. With his wife Betty, Carter returned to Louisiana and in 1932 founded the Hammond Daily Courier as an anti-Huey Long Democratic paper. When the Hammond Daily Courier failed within a few years, Carter moved to Mississippi and founded the Greenville Delta Democrat-Times, which ultimately flourished as Carter’s soundboard for critiquing Southern racism.

Following the outbreak of World War II, Carter and his wife enlisted in different ways in the war effort, with Carter joining the army as a reporter for the Stars and Stripes and his wife working for the Office of War Information. It was during his service years that he encountered Japanese Americans, which inspired him to write an editorial for the Democrat-Times.

Published on August 27, 1945, the editorial was among a series by Carter commenting on the changing racial landscape of the Deep South following the end of the Second World War, as black veterans returned to the destitution of Jim Crow South and sought better jobs and treatment on the West Coast and in cities like Chicago.1 Like many writers of the time, Carter centers his attention on the accomplishments of the 442nd in France and Italy, commending their heroism in saving the 36th Division in the Vosges Mountains and establishing their credentials as some of the best. Most poignantly, Carter noted Japanese Americans “have been on trial, in and out of uniform, in the Army camps and relocations centers,” and seem to “have not satisfied their critics.” Carter warns his readers “too many have committed a wrong against the loyal Nisei, who have by the thousands have proved themselves good Americans,” and advises Americans that “an active minority” of racists “can have its way against an apathetic majority.” If there is learn something from the story of the 442nd, it is, to Carter, adopting the 442nd’s motto and “shoot the works in a fight for tolerance.”

A year later in 1946, Carter received a Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing. While the citation notes his writings on racial, religious, and economic intolerance, the committee noted that it was his “Go For Broke” article that distinguished him.2

The Japanese American community warmly received Carter’s editorial and his winning of the Pulitzer. The May 11, 1946 issue of the Pacific Citizen featured news of Carter’s award on the front page. In later years, Carter continued to advocate for racial equality in the South, both in his columns and in speeches throughout the United States. In 1955, Carter was famously condemned by the Mississippi House of Representatives for his article critiquing the formation of “citizens’ councils” as bulwarks of segregation “in all walks of Mississippi life.” In 1961, after local police refused to protect civil rights demonstrators in Mississippi, Carter argued at a speech in Providence, Rhode Island that federal marshals and the U.S. military should step in. Local students burned him in effigy for his remarks.

Carter continued to interest himself in the fate of Japanese Americans, too. In 1954, Lawrence Nakatsuka praised Carter in the Pacific Citizen, this time for Carter’s editorial in the Saturday Evening Post in support of Hawaii’s statehood. Citing his previous support of Asian Americans, Nakatsuka argues Carter’s support of the Hawaiian Asian community and combatting sentiments of Asians as communist sympathizers exemplified him as an advocate of racial tolerance.3

The loss of his remaining eyesight in 1963, along with his growing alcoholism, led towards a decline in his journalistic pursuits. Following a steady decline in his health, Carter handed the reigns of the Greenville Delta Democrat-Times to his son Hodding Carter III (who would later become White House Assistant Secretary of Public Affairs for, coincidentally enough, President Jimmy Carter). Hodding Carter II passed away on April 4, 1972. The New York Times lauded his career as a journalist who’s task was “attacking and destroying racism whenever he found it,” noting his 1945 article on the Nisei soldiers of the 442nd as turning point in his career that emboldened his stance on racial tolerance.4

Carter’s writings underscore a hidden yet important legacy of the incarceration on American society, and its place within the larger rubric of race relations in the South. As with other Southern liberals, Carter’s stance on race relations was not without its hesitations and critiques. Still, his mission was certainly one that posed its dangers. With a state that was ruled by John Rankin and Theodore Bilbo—two of the most vitriolic racists in the U.S. Congress and vocal advocates of incarcerations—writing in favor of racial tolerance was not easy. As Larry Tajiri noted in a 1946 article on Mississippi in the magazine NOW, one wonders “How can the same state produce both John Rankin and Earl Finch?”5 The same can be said for Hodding Carter II. Although a number of public intellectuals and academics came forward against the incarceration, Carter’s journalistic legacy teaches us how the incarceration serves as a lesson in understanding race relations of the United States and a broader impact on American culture.

Notes:

1. Hodding Carter II, “Go For Broke.” Greenville Delta Democrat Press, August 27, 1945.

2. “Pulitzer Prizes Awarded.” New York Times, May 7, 1946.

3. Lawrence Nakatsuka, “Staggering Blow on Communism.” Pacific Citizen, July 2, 1954.

4. “Hodding Carter Jr Dies; Outspoken Mississippi Editor.” New York Times, April 5, 1972.

5. Greg Robinson, Pacific Citizens, 121.

* This article was originally published on NikkeiWest on April 25, 2020.

© 2020 Jonathan van Harmelen