Nisei swimmer Tetsuo Okamoto (born 1932 - died 2007) brought the first Olympic medal to both Brazilian swimming and the Japanese community. He reached third place on the podium on August 3, 1952, in the 1500m freestyle at the Helsinki Olympics (Finland). What's more, three swimmers of Japanese descent made up the podium at that time. At the time, Japanese newspapers focused on the good performance of the Japanese swimmers at the Olympics. However, despite the lingering aftertaste of the win-lose battle and the strong negative impression of Japanese immigrants, Brazilian newspapers gave extensive coverage of the good performance of the "Japoneses" and heartily congratulated them.

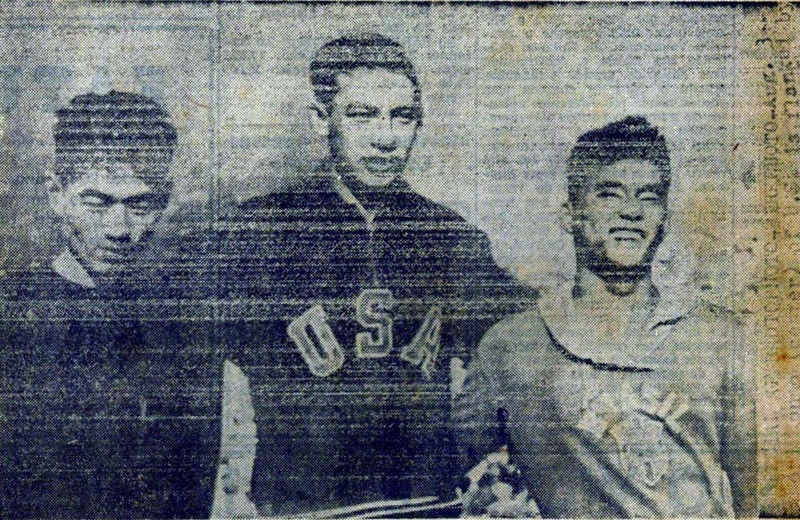

On the afternoon of August 3, 1952, the day of the closing ceremony of the Helsinki Olympics, the winners of the 1500m freestyle swimming competition were: Hawaiian-born Japanese-American Konno Ford in first place (18 minutes 30.3 seconds), Japan's Hashizume Shiro in second place (18 minutes 41.4 seconds), and Japanese-Brazilian Okamoto Tetsuo in third place (18 minutes 51.3 seconds). Okamoto was 178 cm tall, weighed 69 kg, and had a well-trained, muscular body that was imbued with the spirit of a samurai.

According to the August 14, 2004 edition of the Nikkei Shimbun, at the final turn of the 1500m, Okamoto was in so much pain that he nearly fainted, but he heard his father's voice say, "You are the descendant of the samurai. Show us your Japanese spirit before you die!" So he replied, "I don't care if I die now," and swam with all his might. It was a comment that reflected the times.

However, without this determination and determination, he would not have made it onto the podium, as the gap between him and James McClain of the United States, who came in fourth, was just two tenths of a second (18 minutes 51.5 seconds).

When Okamoto was informed of his third place finish, he was so happy that his mind went blank and he began to cry without even realizing it.

Okamoto advanced to the finals with a time of 19 minutes 5.6 seconds (a new record for Brazil and South America) in the qualifying round. This alone was a time worth being proud of. However, in the finals he improved his time by nearly 15 seconds, recording an amazing 18 minutes 51.3 seconds (a new South American record). This was a record that remained unbroken in South America for the next 10 years.

The difference between him and Konno in first place was about 20 seconds, and between him and Hashizume in second place was 10 seconds. In the same event at the Pan American Games in March of the previous year, Okamoto's record was 19.23.3 seconds. By the time of the Olympics a year and a half later, Okamoto had improved his time by a whopping 30 seconds.

In August 1952, immediately after his triumphant return, Okamoto boldly commented in an interview with the newspaper Ultima Aura, "If I had two more months (of training) until Helsinki, I could have aimed for first place." This was the time when the 20-year-old's body had undergone astonishing development.

However, this was not just a result of innate talent; it was also the result of miraculous intensive training that was born out of exchanges between Japan and Brazil.

Swimming with frogs in the frontier pool

Tetsuo Okamoto's father, Sentaro, was not a typical agricultural immigrant. He was an intellectual born in Sapporo, Hokkaido in 1892, and was a free traveller with a surveyor's license who came to Australia from England via the Amazon in 1912. His mother, Tsuyoka, was from Fukuoka Prefecture.

Sentaro even told his son, "You are a descendant of samurai," so it is possible that he was actually of samurai descent from a family that came from the mainland to develop Hokkaido during the Meiji period.

During the Idiro Revolution of 1924, he lived in Conde Street in the city of São Paulo, and was one of the promoters when the supporters' association of Taisho Elementary School (established in 1915) was founded in 1920. In the same year of the revolution, the school moved to Doalcina, and in 1932 it moved to Marilia (which became a city in 1929), where he became a leading figure in the Japanese language education world in the city before the war.

Sentaro also served as president of the Japanese Association of Marilia and was instrumental in establishing the Paulista Extension Teachers' Union and the Paulista Education Society. Every year, the society raised funds to hold school trips, art exhibitions, school performances, track and field meets, and judo and kendo tournaments. In 1937, when Japanese language education was in full swing, there were 1,740 students enrolled in the Pan-Marília region alone (Pan-Marília Thirty Years History, Toyohara, 1959; Nakamura Tomin, Thirty Years History Publishing Association).

Tetsuo was born there on March 21, 1932. His birth registration number was 36 in the town. It was only three years after the city was established. It was one of the first cities to become a regional core city with a population of 200,000 today. He was the youngest of three children, with three older brothers: Yoshio, Yoshie, Suzue, and Kunie.

Tetsuo started swimming at the age of seven, around 1940, just before the outbreak of the Pacific War. Tetsuo suffered from childhood asthma and was encouraged by his parents to start swimming as a way to improve his physical condition.

According to the September 18, 1952 edition of the Paulista Newspaper, Shinzo Tosaki and Yoichi Yamazaki, natives of Yatsushiro-gun, Kumamoto Prefecture, built a "Japanese Pool" on their farm on October 8, 1940, at their own expense. It was 25 meters long and 12 meters wide. The construction cost was supposed to be 30 contos but ended up costing 50 contos. At the time, it was extremely rare for Japanese people to have a pool in such a pioneering area.

Okamoto started swimming in this "Japanese Pool." In the August 14, 2004 edition of the Nikkei Shimbun, Okamoto recounted his early days, saying, "There were no tiled pools in the countryside, so this one was built by damming a stream, and frogs often swam in it. As soon as I started swimming, the water became murky, and I couldn't see anything underwater even if I opened my eyes."

Around the same time, the Yara Club was established and he began practicing there.

The nationalistic policies of the Getzlio Vargas dictatorship, which began in earnest in 1937, banned foreign language education for children under the age of 10 in 1938, and by the end of the same year all foreign language schools in Japan, Germany and Italy were closed, while all Japanese-language newspapers were forcibly discontinued in July 1941. The war years, when Okamoto was around 10 years old, were a time of hardship for Japanese immigrants.

*This article is reprinted from the Nikkei Shimbun ( August 5th and 6th , 2016).

© 2016 Masayuki Fukasawa, Nikkey Shimbun