So actually, just to backtrack a little bit. When you actually left Manzanar to Tule Lake, how did you get there? Did they put you on a train?

Yeah we got on a train. I guess a lot of people were happy, I wasn’t too happy. Tule Lake is horrible. You ever see Tule Lake? Compared to Manzanar? It was horrible because Tule Lake was a dried out lake bed. No soil in there at all it’s like little gravels. Where on the other hand, Manzanar was in the desert but it was in a sort of an oasis of the old days where they had apple trees and pear trees in the firebreaks. Whereas Tule Lake had nothing growing, there wasn’t even weeds growing in Tule Lake and the only foliage I saw was a potted plant in front of the admin building. Manzanar became pretty nice because the Japanese started planning lawns and put gardens in-between the firebreaks and that cut the dust down a lot. And then we had the fresh water from the Sierras coming down. Clean, fresh water. Whereas when we went to Tule Lake, the water was well water, and we were close to Mount Shasta so it was sulphuric water. And first time I went to the mess hall in Tule Lake I go, “How come the rice is yellow?” They said because of the sulfur, the water was well water. It was horrible.

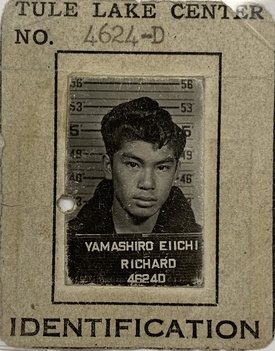

And where were you placed in Tule Lake?

When we went to Tule Lake they had started an addition to Tule Lake because of the amount of people going there so, we’re in a pretty nice barracks, it was the new barracks. And that part of the camp became known as Manzanar.

And what year was this that you actually left Manzanar? Was that 1943?

Yeah, I think it was — might have been ’44, I’m not sure. ’Cause we stayed in Tule Lake two years.

And your Dad obviously kind of took the family there. So how was he at this time, living in Tule Lake?

Well, he became one of the —

Kind of pro-Japan?

Yeah and he got sent to Santa Fe, New Mexico. I don’t know if he was a rabble-rouser, I didn’t think he was a rabble rouser. But he got sent to either Santa Fe or I’m not sure if it was North Dakota. They didn’t want troublemakers, so they kept sending all these people. Pick ’em up and they send them out to another camp. So I didn’t see my Dad ’til we got on the ship to go to Japan.

How long after you arrived did he get picked up and sent?

I’d say he was in there maybe a year.

And you know what happened?

I don’t really know. But Tule Lake was a weird camp because they had all these pro-Japan people. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of the wasshoi boys? I was one of them. But that was only because I didn’t want to do that. But then you have all the peer pressure and all the people that all my friends, you know, they were in these groups already. It was called Hokoku Seinen Dan, and we would get up at five o’clock in the morning, go out there and bow to the east and we would do calisthenics. And we would wasshoi around the camp with the hachimaki. I stayed out of it as long as I could and then peer pressure got too much. My Dad and them said they want me to join. I said, “Who the heck wants to get up early in the morning?” Anyway I joined them, unfortunately I was one of the wasshoi boys. It’s kind of scary, when we first got to Tule, they had just had a riot and they had the armored car patrolling the streets. I go, what kind of camp are we in? It was rough. We had a lot of Kibeis. They were really rabble rousers.

But your Dad, he became kind of involved.

I don’t know how he became involved, but I know he got picked up and sent to another camp.

Right. Was your Mom upset?

Oh, I think she was, but my Mom was pretty cool. She was teaching nursery school. I don’t know exactly what happened to my Dad. But I know he must have been in some group. Yeah, they used to make us sing Japanese wartime songs.

They’re trying to prepare you right, to go back?

Well, they even sent us to Japanese school because preparation of going to Japan, they sent us to Japanese school.

So you said you didn’t see your Dad. What happened when you left Tule Lake for Japan, and you said you didn’t see your Dad until you got on the boat?

Yeah. But I was happy to see him, but I wasn’t too happy about leaving ’cause like I said, I didn’t want to go to Japan but I didn’t have a choice. I remember we were on a ship called the General Gordon. And we left Portland, and we’re going down the Columbia River. I kind of worked my way up to the decks so I could see. And I really felt sad because I saw Portland going by and I said this is my country I don’t know when I’m going to be able to see this again. I felt sad. There’s nothing I could do. That was the roughest boat ride I ever had. We hit a storm going over. Oh, it was horrible. It was so bad that the boom on the ship broke during the storm and the ship would go and hit the wave and the bow would go way out of the water, and then it bobs down but in the meantime, the tail would go "boom boom boom boom boom."

Wow, scary.

Yeah, and everybody was sick. Everybody was sick. And they had us stuffed in there like animals. It was a troopship. But I found out that the best place to be is in the galley, which is at the center of the fulcrum of the ship. So I used to go down and work in the galley.

How long did that take?

I think it took, if I’m not mistaken, two weeks.

It’s hard to imagine.

It was horrible. Then we got to Japan, it wasn’t too good either. Japanese had these big buildings with all tatami, it was like a naval barracks or something. And they had this camp, the segregation center, where people from all over the South Pacific were coming back to Japan. So we had people from all the islands and all that stuff. They told us be careful with our baggage. And so we had to practically sit on baggage otherwise somebody would steal it. And I’m eating this food they gave us, napa soup, and we’re sitting inside, eating the napa soup. It wasn’t too bad. One day I see this extra protein in the bottom [laughs]. I quit eating napa soup. That was something else. And they told us not to wander too far from the camp there because Japan was really bad and people would mug you for your clothes. So we stayed ’til we went to Hiroshima.

Wow. So I mean, you’re just mad with your father.

Yeah, I was mad with my Dad because - but that was after we got to Hiroshima. I told him I’m going back to my own country as soon as I can first chance I get. I said, “I don’t know what you’re gonna do, but I’m leaving.” And I left home, 16 and I got a job with Australians. They gave us room and board, so lived in the barracks there with a couple of other guys.

Was your father upset with you for leaving?

No, he was very apologetic because Japan was really bad. But, you know, I’m just thinking about myself. And I wasn’t really thinking about his feelings, you know, until I got a little older. I couldn’t understand why he went back but then I realized later on in my life that he lost everything he had worked for. I guess that was general consensus for all the Isseis. They worked all their lives and boom, it’s gone. It’s not that we had any land or anything but that was just what he worked for.

MS (Michael Sera): Did he ever come back to the U.S.?

Yep. That’s another story. When I went back and I joined the army and went to the language school and my sister said, well, she wants to go back, too. Because she got her citizenship reinstated. So she came back and stayed in Monterey with us. And my mom says, “Well, the kids are back in the United States. I want to go back, too.” And so I had to put in for a visa for her to come back. And my sister-in-law, she worked for somebody in Congress, you know she was doing domestic. And so that kind of helped. Because he helped me get her a quota to come. So she comes and my Dad is all by himself and he says, “Well, I want to come back, too.” So I had to go through the quota thing for him too, get a visa. He finally came back. So the family got reunited at Monterey.

But he was there by himself for a little bit.

Yeah. He worked in Etajima. That used to be the naval academy, he worked there. But he finally came back. So I got all my family back in Monterey.

And by this time, did you say you had been married?

Yeah.

* This article was originally published on Tessaku on February 26, 2020.

© 2020 Emiko Tsuchida