Can someone be trusted as a Japanese person just because they have Japanese citizenship?

As I was reading the comments section of the journalist's column "Brazilians in Japan should also be given 100,000 yen, " I noticed that many people were lumping together permanent residents and short-term visitors when it came to foreigners in Japan, and that there were strong preconceived notions about nationality.

For example, something like this:

"I mean, foreigners have foreign nationality, which means that that country has an obligation to protect its citizens, so shouldn't we just ask such people to return to their home country?

Whether you pay taxes or not should be interpreted as a necessary fee to stay in Japan.

There's no need for the Japanese government to protect people with foreign nationality to that extent.

There is no need to pander to foreigners to that extent. I believe that the only people the Japanese government must protect are "Japanese people with Japanese nationality." (Omitted)

The author of this article has a misguided way of thinking and is shameless in his ideas. If you can't make a living, go back to your home country."There's no point in introducing the My Number system."

Protecting foreigners is something that each country should do, not something that Japan should bear.

Even if they pay taxes, they don't have Japanese nationality.

I feel that people who write such comments do not understand the opposite of what it means to be a foreigner in Japan: the Japanese as a foreigner.

There are many Japanese people living abroad who have naturalized in their country for work or other reasons. However, there are also people who are proud of their Japanese nationality and continue to hold on to it. This is a kind of "remote nationalism" phenomenon, and there are many immigrants in Brazil who are proud of being Japanese, even more so than the Japanese in Japan.

The same phenomenon can be seen among foreigners living in Japan. In other words, there are many cases where people say, "I love Japan and want to live here permanently, but I want to keep my original nationality as much as possible."

"Nationality" is a basic attribute that comes with one's birth. In contrast, the attribute of "foreigner" is something that one acquires later, whether they like it or not, as they may have been taken away by their parents at a young age. However, because one can become naturalized, it is difficult to say that nationality expresses one's mentality or identity.

Rather, it is dangerous to be overconfident about one's nationality. Just because someone has nationality does not mean that they are "100% Japanese at heart."

For example, about 20 years ago, I interviewed a Brazilian soccer player (with Japanese nationality) who was playing for the Japanese national soccer team at the time. I met him in Sao Paulo when he returned to his hometown.

I assumed that since he was a Japanese national team player, I would be able to interview him in Japanese, but when I spoke to him, he said, "This is Brazil, so I'm Brazilian. They don't speak Japanese here, so you should ask me questions in Portuguese."

Since he had dual nationality, I thought there was some truth to what he said, and interviewed him in Portuguese. However, something remained unsatisfactory. Of course, he is considered "Japanese" in Japan.

Just because you have Japanese nationality doesn't mean you can trust someone as a Japanese person. Nationality is just one factor to consider. What's important is whether you like Japan and want to live here permanently.

I want to see "Blood Memory" made into a movie

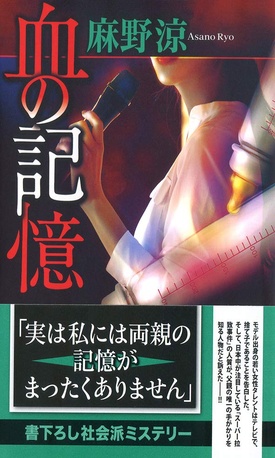

Thanks to the Quarantine, I read an interesting social mystery novel called "Memories of Blood" (Ryo Asano, Bungeisha Bunko, 2020). Strangely enough, the protagonist is a foreigner living in Japan.

The protagonist, SUMIRE, is a young female model-turned-talent who is popular on variety shows with her distinctive appearance that seems to have foreign blood in it and her witty comments that make people laugh. She was abandoned as a baby in front of a hospital in Shibuya Ward and was rescued. She has a mysterious origin: "I have no memory of my parents at all."

The reason he entered the entertainment industry was out of a fleeting hope that "if I became famous, my parents would come forward."

The incident occurred at a supermarket in Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, which is famous for the large number of Brazilian workers in Japan. Just before closing time, an Asian foreigner kidnapped the daughter and grandson of the president of a local global company. The perpetrator's demand was not the usual large sum of money, but the unreasonable demand to "cut off the president's left hand."

This is combined with the true events that occurred at factories all over the country, when the boom in dekasegi workers by Japanese-Americans began in 1990, and during the Lehman Shock in 2008, when serious accidents occurred in which left hands or fingers were amputated in what appeared to be unnatural ways, and the identity of the culprit gradually becomes clear.

It turns out that SUMIRE's father was a foreigner who worked for the same global company, and when the perpetrator sees her commenting about the incident on a news program, he takes a surprising action. From there, the story develops rapidly, leading to an unexpected ending.

The story also features a unique character called BJ, a black-Japanese musician who plays at a bar in Roppongi, Tokyo. The character is based on a real person, a black-Japanese man who grew up in the Elizabeth Sanders Home (Oiso, Kanagawa Prefecture), which looked after mixed-race children born to American soldiers of the occupying forces and Japanese women.

After seeing eight of his fellow orphans emigrate to the Second Home (Saint Estephanie Farm) in the Tomé-Açu settlement in the state of Pará, Brazil in 1963, he dreamed of going to Brazil himself, but he gave up on the idea after encountering problems such as the government being reluctant to issue visas.

The final scene, which shows the abduction scene and the TV studio mixed together, will have you on the edge of your seat.

This is a story that I would love to see adapted into a movie or TV drama, starring a real-life popular idol.

The people referred to as "Korean residents" are not limited to Koreans or Chinese. "Memories of Blood" is peppered with images of the "diverse residents of Japan" who cannot be easily measured by appearance or nationality.

Dramas and films depicting the history of Japanese Americans before and after the war have been produced, such as "99 Years of Love: Japanese Americans" (2010), which commemorated the 60th anniversary of the founding of TBS, and "Haru and Natsu: The Letter That Never Delivered," a drama starring Sugako Hashida, which commemorated the 80th anniversary of NHK broadcasting (2005).

However, there are only documentaries about "current Japanese people living abroad," and I feel like there aren't many dramas about them. What do "Japanese people who have become foreigners" think and feel? I'd like to see someone who can present the globalized everyday life, and the writing and images that crystallize it, come forward.

If it is easy to imagine a Japanese person becoming a foreigner, then perhaps we can come up with a uniquely Japanese approach to how to treat foreigners within Japan.

I would like to see more stories like "Memories of Blood" featuring foreigners as the protagonists who decide to live in Japan permanently, as well as dramas about Japanese people living abroad who are permanent residents, depicting the reality of globalization and the fact that Japanese people can become foreigners, and weaving this into common Japanese knowledge.

*This article is reprinted from the Nikkei Shimbun (May 5, 2020).

© 2020 Masayuki Fukasawa / Nikkey Shimbun