Tenning-san

The man called “Tenning-san” refers to Jujiro Takenouchi (1869–1937), who grew up in Kuwana, Mie, graduated from Navy Comptroller School at the top of the class, and in 1898 he was posted in London, England as the military officer at the Japanese Embassy. Lieutenant Commander Takenouchi was in charge of building warships as a preparation for the Japan-Russo War. While there, a great amount of unaccounted funds for expenditure was revealed. At the military tribunal in Japan without his presence, Takenouchi was sentenced 11 years for the deficit of approx. 30 million yen in today’s rate. He disappeared and took asylum to Canada in 1904 and there he changed his name to “Jusan Tenning” after his nickname “Ju-san” from “Jujiro.”

Miyoko Kudo, a non-fiction writer, wrote about Takenouchi in her book, Love in Vancouver, that he ran away from his residence in London because he had invested the military budget on behalf of his superior but could not recover the deficit; thus he was made to take all the responsibility for the loss.

However, another non-fiction writer, Ryuzo Saki, wrote in his book titled, No Shadow of Sunset on the Waves, that unaccounted funds had been remitted to his superior Navy officer to be passed onto a politician, apparently as a bribe. But when that bribery scheme was likely to be discovered, Takenouchi’s superior officer died an unnatural death. It fell on Takenouchi’s shoulder and he was blamed everything for the unaccounted funds. He escaped to Canada and worked as a farmer hiding in Winnipeg.

In 1929, he came out to Vancouver to work for the local Japanese media and for the Japanese Fishermen’s Association. His expertise in English and politics was highly respected by local journalists such as Etsu Suzuki, the publisher of Minshu Newspaper, who deeply sympathized with his shadowy past. However, Etsu’s sudden death in 1933 made him depressed and addicted to alcohol. Toward the end of his life was miserable; “He wouldn’t work when sober but couldn’t work when drunk” (Rintaro Hayashi, Beyond the Black Current).

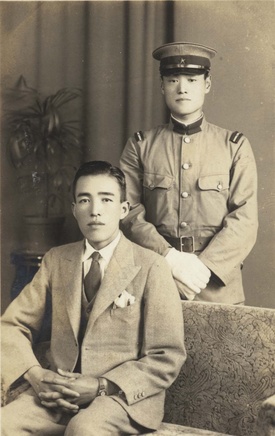

Former Lieutenant Commander Jujiro Takenouchi, after he moved to Vancouver, desperately tried to go back to Japan to retrieve his honor. But his last hope was harshly shut out by his former senior officer with the words “I have nothing to do with such a person.” Takenouchi passed away in 1937 at a hospital in Vancouver leaving a note “Unenviable was the burdens of official responsibility.” Takenouchi left seven children behind. One of his five Nisei Canadian daughters, smiling in the photo below, was a member of Fuji Ski Club, according to Shozo Miyanishi.

Swimmers of Burrard Inlet

“Swimming in Lake Biwa was a joy of summer break in my public school days,” said Shozo. In the 1910s, at Iso Irie Public School, he used to compete with other kids by swimming in the lake for about four kilometers from the front of the school to the edge of the village. At the age of 15, after finishing higher elementary school or koto-shogakko, he returned to Vancouver. He got a job at Akiyama Hardware Store which sold kitchenware, ceramic goods, and carpenter tools. He worked there for ten years as a clerk until 1937.

In 1932, at the age of 20, he participated in the eight kilometer swimming race from North Vancouver to the beach at Hastings Park for the first time. “There was a friendly white guy working at a ceramic wholesale dealer, who loved long distance swimming. When he found that I loved swimming too, he asked me if I’d like to join him.” Among around one hundred participants, Miyanishi was the only Japanese. “Of course, I made the goal.”

The next year’s long distance course was even tougher; swimming across the mouth of Fraser River where for the first two miles or so, high triangle waves moved towards the outer sea. “That part was very hard to cross. But my friends cheered me on, rowing a boat along with me. They were five or six Niseis from the Japanese school alumni called ‘Hokuto-kai’.” He showed me another photo of the Class of 1932, “Gakuyu-kai”: 20-year-old Shozo Miyanishi is seen at the far right in the front row.

Torn apart between two home countries

In 1937, Shozo quit his job and headed for Japan together with his friend Kanzaburo Kobayashi. The two wanted to see their best friend, Tameo Noda, from Mio, Wakayama Prefecture, who had been conscripted to the Heijo (Pyongyang) 77th Battalion. Noda used to play with Asahi in Vancouver known under “Ken Noda, pitcher” as registered in the 1933 roster.

During their stay in Japan, the Marco Polo Bridge incident happened on July 7, 1937. Immediately, the two packed their trunk and hurried to the boat to come back to Canada. “Luckily, we had Canadian birth certificates, which did work.” If they had missed the boat, they might have been drafted to the military service. Their best friend Tameo would die in battle during the Second Japan-Sino War.

Back in Vancouver’s Japantown, when the news from Japan was screened at the United Church on Powell St. sponsored by the local Japanese veterans’ group, Shozo saw the figure of Corporal Tameo Noda who carried a military sword. “Tameo’s mother bought the news clip as his memento.”

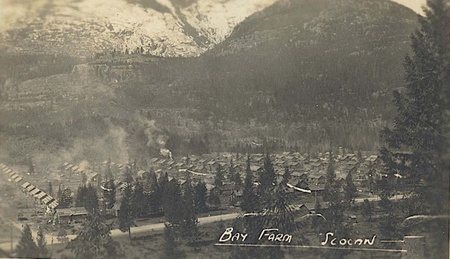

Shozo got a job at the oyster farm owned by Maekawa Fish Store on Vancouver Island and worked there for several years. In April 1941, he married Toshi Tanaka, a daughter of a friend of Shozo’s father who was from the same village in Shiga Prefecture. When the Pearl Harbor attack happened, Toshi was pregnant with Doreen who was born in Vancouver in 1942. Soon after, the Miyanishi family were interned at the Bay Farm Internment Camp in Slocan. Later Shirley was born in Slocan in 1945.

After World War II, when the Japanese Canadians were required to choose to move further to eastern Canada or head for war devastated Japan, the Miyanishi family chose Japan. “Our grandfather was there with a house to live in and a farm for us to cultivate” answered Shozo’s second child, 74-year-old Sachiko Shirley, responding to my email interview. When food supply was scarce in Japan, only the farmers had plenty of food to feed family. “However, my mother never had experience working on a farm. She must have had a hard time,” Shirley added.

On August 2, 1946, the US-chartered troop transport ship, General M.C. Meigs, arrived at Uraga, Japan carrying 1,377 Japanese Canadians. Shirley was only 10 months old. Shozo began to work at the Occupation Army Camp in Otsu.

After 10 years of working there and when the camp was closed, the Miyanishi family decided to return to Canada, as they had agreed on long before. Shozo explained, “The late Tameo Noda’s mother offered me, saying that if I would come back to Canada, she would welcome me as her son, on Tameo’s behalf.”

Like salmon return to where they were born

In 1956, before leaving Japan, Shozo visited Mio Village to say his farewell to the gravestone of his late best friend. Shozo started working at a mushroom farm in Ontario. In 1959, the rest of his family joined him. According to Shirley, “As we had anticipated to come back to Canada from the first, we all had maintained our Canadian citizenship.” When they came back, Sachiko Shirley was 13 years old, first son Masakazu was seven. The youngest child, Ron was born in Toronto in 1960.

Shirley continued, “I was enrolled in grade six after we returned to Canada. That’s when I received special English tutoring from my school’s vice principal for about a year, early in the morning before the class started.” She declared that she, nor her younger brother Masakazu, had much difficulty in adapting themselves to Canada. While, “My sister Akemi Doreen was 16. She must have gone through the hardship of cultural differences.” Settled in Toronto, father Shozo was hired as a school maintenance worker for the North York School Board. He worked there until his retirement.

The late Shozo Miyanishi (1912–2006) plied back and forth between Canada and Japan roughly five times: he was born in Canada, educated in Japan, and was back in Vancouver at the age of 15. Then, he took his family to Japan in 1946 and again came back to Canada in 1956 at the age of 44. Four of the Miyanishi family members were Canadian born, like salmon who eventually come back to the river where they were born, their unconscious memory must have called them back to Canada.

*This article was published in the Japanese section of the JCCA Bulletin as a 4-part series in 2019. The above English edition was rewritten and translated by Yusuke Tanaka in collaboration with Ron Miyanishi. Photos are courtesy of the Miyanishi Family.

© 2001 Yusuke Tanaka