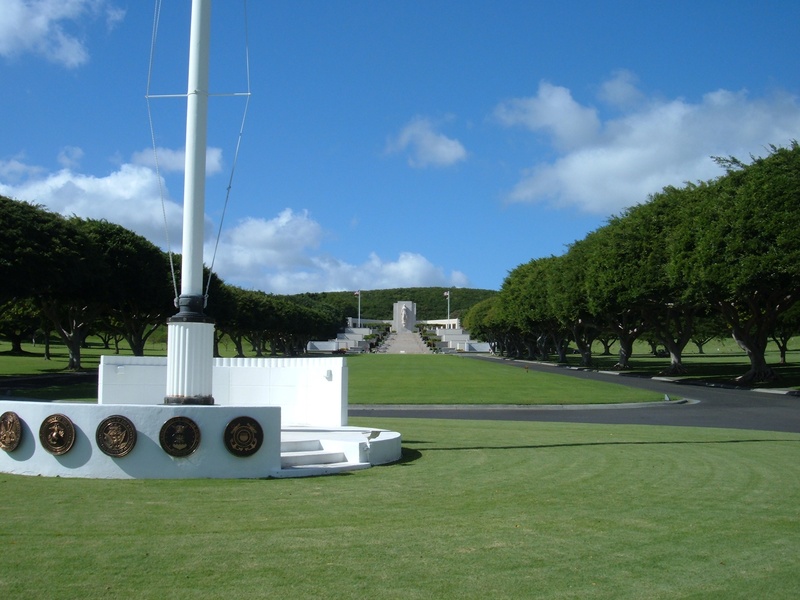

I awoke this morning to memories of the cowboy lament, “Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie.” Perhaps the memories had been triggered when I had confronted my mixed feelings about where to be buried. Last evening, I had decided to request burial for the ashes of my deceased husband, Hank, at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known to many as the Punchbowl Cemetery, close to Pearl Harbor. Hank had served as a Captain in the United States Army in the Vietnam era. As Hank’s widow, my ashes could be placed with Hank’s ashes in Punchbowl Cemetery. Punchbowl Cemetery is a beautiful cemetery, meticulously maintained to military standards. It would be an honor to be buried with so many famous patriots. Our beloved son Mark had suggested the site to me.

Before he died, Hank and I had agreed upon having our ashes scattered somewhere in the Pacific Ocean similar to the scattering of his parents’ ashes in Puget sound. Unlike Hawaii, where there is opposition to the scattering of ashes in Hawaiian waters, the Washington State Ferry system allows, even now in 2020, scattering of ashes in Puget Sound in a short but meaningful ceremony. This very un-Japanese form of burial, without graves in a formal cemetery was selected with careful thought by Hank’s very Japanese parents who, though born in America, had spent their childhoods and young adulthoods in Japan.

They didn’t want their children to be burdened with finding an appropriate cemetery and having to maintain their graves under the watchful eyes of critical Japanese and older Japanese Americans who would comment upon the care with which the graves were maintained. In one brilliant stroke, Mom and Dad Yamamura took this burden off their children but retained a way to be remembered every time their children looked at Elliot Bay in Puget Sound. The entire Yamamura family, including myself, had spent many happy hours fishing in Puget Sound. But those waters are very cold and as my husband lay dying he often shivered with a feeling of cold that could not be warmed. He told me he wanted to be buried in a warm place.

I had spent years laboring to get ownership and then trying to maintain one of the graves at the famed Kyoto Otani Cemetery of an ancestor by adoption who had been a favorite student of Yoshida Shoin. This tie to Japanese history entangled me in a complex web of changing customs and disappearing ancient Japanese traditions which finally became too much for me to manage. I relinquished my hard-won ownership of this ancestor’s grave, with the aid of my son, knowing that there was a second grave for that ancestor maintained by Ube City in Yamaguchi-ken, Japan. Care of the graves of ancestors is often referred to as “ancestor worship” in America. But to me, this custom represents deep respect for ancestors and certainly not worship. For me, it was an important way to learn family and Japanese history. It is also a major source of revenue for the members of the Shinto and Buddhist groups maintaining the cemeteries. I know this revenue source is declining in Japan as younger Japanese have different ideas about ancestors and graves, just as my son has a very American and Christian view of burials and grave maintenance. Grave maintenance is not an issue at Punchbowl.

One of my reservations was about having Hank’s and my remains in Hawaii. It would be a long way to go to visit our graves from the mainland. This final reservation was laid to rest when my son told me he did not customarily visit graves of the dead. Once again, I had been thinking in terms of old customs which were irrelevant to the younger generation.

There are other Japanese customs regarding funerals and burials which persist in America. Customs such as koden, the giving of money at funerals, including an elaborate bookkeeping system for amounts received by person, returning koden at the funerals of family members of those giving koden, are no longer observed by many Japanese Americans. There will be no koden exchanged when I die. There will be no elaborate celebration of life or funeral/burial ceremony – only a simple, non-denominational, immediate family-only gathering, organized by my son. My ashes will be buried at Punchbowl Cemetery in the same place where my husband’s ashes will be buried. The circle will be completed with my burial close to Pearl Harbor and the USS Arizona. I was incarcerated in Camp Harmony and Camp Minidoka after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor because I was an American of Japanese ancestry. If all goes well, I will end my days in the state of Arizona and be interred close to Pearl Harbor.

© 2020 Susan Yamamura