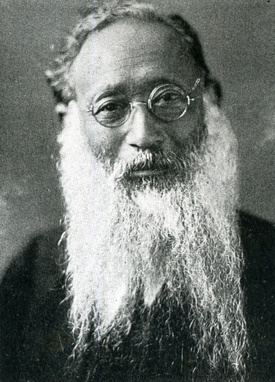

After finishing the visit to the company, I casually looked at the used book section at the entrance to the editorial department, and saw the back of a man with a familiar, distinctive beard. "We have a rare visitor," I said, and it turned out to be a ceramic artist, Tetsunori Nakatani (Akinori, 76, originally from Osaka City, Osaka Prefecture), who lives in Kokuera, Moji City.

"I brought this because I just published a book," said Nakatani, handing me his collection of works, "AKINORI NAKATANI sua obra e sua vida" (Portuguese: Enock Sacramento, Giovana Delagracia). I was surprised when I opened it. I was impressed that he actually made these kinds of works his main occupation. They were not household items, but ceramic carvings (ceramics as sculptures).

To be honest, I had a strong impression that Nakatani was a strange person who was determined to push forward with the Casarons de Chat restoration movement, even though it would not bring in any money.

The 1920s: When famous conglomerates arrived in Brazil

"Cazaron de Cha" is another name for a tea factory built in the time when the Cocuela district of Mogi was still a tea-producing region. Gosuke Imai of Katakura Silk, a core company of the Katakura Zaibatsu in Japan, purchased the land with his own money, and agricultural graduate Fukaji Furihata and carpenter Kazuo Hanaoka were involved in the construction, which was completed in 1942 during the war.

After diplomatic relations between India and Europe were severed during World War II, and the price of tea soared, the building was used as a full-scale tea factory until the 1960s. It was later used as a warehouse, and in 1986 it was designated a federal cultural property in recognition of its artistic, historical and archaeological value, but it had fallen into disrepair.

The Katakura Zaibatsu was so large that it was dissolved by GHQ after the war. The second-generation Katakura Kanetaro (1863-1934), known as the "Silk Emperor," expanded and developed the silk-reeling company that his father founded in Suwa-gun, Nagano Prefecture, and built it into a major zaibatsu representing the prefecture. In 1922, he made an extended tour of Europe, the United States, and Latin America. It is believed that he focused on Brazil during this time.

The second generation's younger brother was Gosuke Imai. With his economic power as a backdrop, he was elected as a member of the House of Peers as a large taxpayer in 1918, and appointed as an Imperially appointed member of the House of Peers in 1932, a position he held until his death in 1946.

When Nagata Tadashi, also from Suwa County, Nagano Prefecture, became chairman of the Nippon Rikkokai and proposed the construction of the Alianca colony in Brazil (1924), Japan provided support for this.

According to Nakatani's article entitled "The Movement to Preserve Casarón de Cha," which was published in our newspaper on December 17, 2005, "The then owner of Katakura Silk Mill, which was originally located in Nagano Prefecture, sent Bachelor of Agriculture Hibari Fukashi, a graduate of the Faculty of Agriculture at Hokkaido University, to Brazil at his own expense and purchased a farm of 170 acres (Cocuera Farm) under the name of Katakura General Partnership in 1926."

Looking back, the late 1920s was an amazing time. It was a time when Japanese conglomerates rushed to enter Brazil. For example, in 1927, Hisaya Iwasaki, the eldest son of Mitsubishi founder Yataro Iwasaki, established Higashiyama Farm in Brazil. The person sent as an advance team was Yoshitaka Yamamoto, who played a key role in the reorganization of the colonia after the war.

It was also in 1926 that Tokushichi Nomura, who founded Nomura Securities and Nomura Life Insurance (now Tokyo Life Insurance), established the Nomura South America Farm in Bandeirante, Paraná.

It was in 1929 that Sanji Muto (president of Kanegafuchi Spinning) planned the settlement of the Amazon and worked hard to establish the South American Colonization Company, which realized the dispatch of the first immigrants to the Amazon. This year, the 90th anniversary of that event is being celebrated locally.

It was in 1929 that Takeo Ushiromiya, one of the successors of the Ushiromiya financial conglomerate that had been extremely successful in Taiwan, came to Brazil as a member of the South American inspection team of the Keio University Industrial Research Association. He immediately purchased 2,000 acres of coffee in Cornelio Procopio, Paraná, and started a large coffee farm.

It was within this larger context that Casarón was built. There are about 60 federal cultural properties in the state of São Paulo, but there are only two that are related to Japanese immigrants: the rice mill and warehouse buildings built by Kaigai Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha (KKKK) in Registro, and Casarón. These are valuable structures.

Ochayashiki: A Japanese-style cultural space where violins resonate

The local farm manager of the Katakura Partnership Company, Hikaru Hikaru (1891-1971, Nagano), was a bachelor of agriculture, which was still rare at the time. He published the first full-scale publication in the Colonia magazine, the monthly magazine "Agriculture Brazil" (Nouji Tsushinsha), in 1926 using bold movable type printing, and led the agricultural world.

That flag was raised by the Suwa-born carpenter Hanaoka Kazuo, who built Casaron. This famous Japanese building was born from a network of people with strong ties to Nagano Prefecture. The main part has a truss structure common in the area and is roofed with Western tiles. However, the entrance is infused with Japanese design, and the interior pillars and stairs also have a curved design that makes use of natural branches, creating a unique atmosphere. When Columnko saw the building for the first time, she thought it was a Japanese-style Gaudi.

During a tour of the prefectural federation's hometowns in November 2011, participant Yoshiko Fujikawa (Okayama Prefecture) told us a valuable account of her experiences working at Casaron for three years from 1947, just after the end of the war.

"The manager always boasted that we didn't use a single nail. At that time, there must have been 20 or 30 tea pickers like me working there. Apparently Fuki's son was in an orchestra in São Paulo, and he would often come to Casarón in the evenings to practice the violin," she recalls with a dreamy look on her face.

The moment the tea-picking girls stopped busily rolling the tea and packing it into bags, the sound of a young man practicing classical music on the violin echoed from the second floor of the tea house overlooking the tea fields in the setting sun - a scene reminiscent of the Coquela Cultural Village of that time.

By the 1980s the building had fallen into a state of complete decay and was essentially abandoned, but Nakatani fought alone, founding an association in 1996 and beginning a restoration movement that took 12 years to complete, right up to 2008, the 100th anniversary of Japanese immigration to the area.

The aforementioned article also states, "When we began our movement to preserve Casarón do Cha, we established the association as a private non-profit organization, and nine years have passed since then. Before founding the association, we sought cooperation in preservation from the local Japanese Association in Cocuera, the Moji Cultural Association, which is an alliance of Japanese associations in the Moji region, and the São Paulo Cultural Association, among others. However, the response was slow, and in the end we were unable to get any cooperation, so we decided to set up our own association. When the association was first established, the local Japanese Association was more or less turning a blind eye to our preservation efforts."

During this time, I remember that Nakatani-san visited the editorial office many times and passionately explained the significance of the restoration of Casaron. At that time, he never talked about his main job, but only talked about the significance of Casaron.

*This article is reprinted from the Nikkei Shimbun (October 8, 2019).

© 2019 Masayuki Fukasawa / Nikkey Shimbun