I cannot recall precisely when I first heard of Tamio Wakayama. Although I owned a copy of A Dream of Riches and had looked through his 1992 book Kikyō – Coming Home to Powell Street, I had only a rather vague sense of him until about 10 years ago, when I began hearing about a Japanese Canadian who had once been active in the civil rights movement. As a historian who had focused on connections between Blacks and Japanese Americans, I was definitely interested. I spoke about Tamio with Allyson Nakamoto, director of educational programs at the Japanese American National Museum. She had joined with Tamio on a program commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides. At my request, she wrote an email putting us into contact. I followed up by writing Tamio. I informed him that I habitually visited Vancouver once or twice per year, and asked if I could interview him the next time that I came to town.

Thus it was that I got to meet Tamio on my next trip to Vancouver, in February 2012. He agreed to come downtown for a chat/interview with me and my partner Heng Wee. In order for me to better prepare questions, he sent me a draft of his unpublished memoir. Knowing of his long career as photographer and activist, I initially felt a bit intimidated at meeting him.

As Tamio came into the café where we had agreed to meet, I caught my first glimpse of him and shook my head. I think that I must have been expecting a venerable and polished public figure. He was already 70 years old by that time, but looked to be in his early fifties. He wore baggy, comfortable clothes, topped by an aged and slightly misshapen slouch hat which I soon learned was his trademark. Another trademark was the well-worn bicycle on which he relied for most of his transportation within the city. Even in inclement weather, he insisted on pedaling to his destinations. Eventually, he was able to buy an electric bike, which made going up the city’s hills much easier for him. Whenever he went out, Tamio wore a yellow orange reflective vest, which gave him the look of a construction worker. I thought of this as amusingly eccentric behavior on his part until I discovered that his late father had been killed while riding home one night, when his bicycle was hit by a car whose drivers had not seen him.

From the beginning, Tamio was quite open and engaging. While he expressed his sincere affection and regard for the people he had met in the Black freedom movement, and he was clearly proud of his contributions, I saw that he was a quiet man who was reticent in speaking about himself. In fact, he expressed greater interest in asking about my researches on historical connections between blacks and Asians, about which he knew very little, and in getting me to talk about them. I also saw that he did not take himself too seriously. Instead, he played the curmudgeon, and soon had me laughing at his views of people and things. Even more, he was fascinated by ramen, and thereby bonded with Heng Wee, a passionate ramen aficionado. Tamio shared with us his favourite restaurants and discussed his methods of preparing it at home.

A month later, I traveled to the Japanese Cultural and Community Centre in Toronto to attend the Keisho conference on Japanese Canadians and World War II that Tamio’s older brother Peter Wakayama had helped organize. There I saw Tamio, who had come east to attend. He was there with his partner Mayu, whom I instantly adored. Mayu’s warmth and vivaciousness perfectly complemented Tamio’s mordant wit and taciturnity, and they shared many interests. (In seeing their complementarity and close connection, I thought of Ralph Martin’s comment about Larry and Guyo Tajiri, the husband-and-wife team of Nisei journalists, to the effect that sometimes it was hard to tell where Larry ended and Guyo began).

A highlight of the conference presentations was the premiere of filmmaker Chris Hope’s documentary Hatsumi. After the screening, I spent a lovely evening over drinks with Tamio, Mayu, Chris, and Peter. The next day, I gave a brief talk mentioning the need for an additional conference on Japanese Canadians in the postwar years. Tamio chimed in publicly to express his agreement, and left me bursting with extra pride when he referred to “Greg Robinson, who is fast becoming an old friend.”

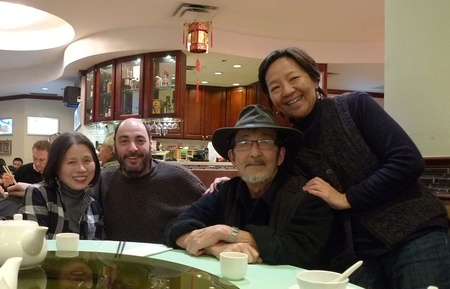

I next saw Tamio and Mayu several months later, when I returned to Vancouver with Heng Wee. We met for dinner as a foursome and all hit it off. During our evening together, I discovered that Tamio and Mayu were close to Judge Maryka Omatsu, an important legal scholar and Canadian redress advocate. I was an admirer of Maryka’s, and so I wangled an invitation to meet her and her husband Frank Cunningham in Tamio and Mayu’s company. Heng Wee and I had such a good time that we began the practice of triple-dating with the two couples whenever we were all in Vancouver.

Another interesting connection that I made through Tamio was with Ed Nakawatase, a Japanese American from Seabrook, New Jersey who had gone South to join SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) during the civil rights movement, then had later become an Asian American activist in Philadelphia. Ed was the only other Nikkei that Tamio had seen in the Black freedom movement. The two had worked together, and they remained so close that Tamio referred to him affectionately as “Brother Ed.” I had the chance to meet Ed when I passed through Philadelphia, and he proved to be a wise and engaging person.

The only time that I actually worked together with Tamio was when we both spoke at the Japanese American National Museum conference in Seattle in mid-2013. I was tapped to present on a panel on multiracial activism, alongside Tamio, Diane Fujino, and Daryl Maeda. Tamio thought that it would be a great opportunity to deliver a section of his unpublished memoir, “Soul on Rice,” and to show slides of his photos. However, there was no AV system available at the conference hotel, and rentals were prohibitive. Tamio finally resigned himself to being unable to show images at the conference.

Luckily, some time before it started, Tamio met up with his old friends Nelson Dong and Diane Wong. Nelson was a distinguished international attorney in Seattle. When Tamio explained his predicament, Nelson kindly offered to lend his company’s slide projector for the conference. So with Nelson as donor and Mayu as projector operator, Tamio was able to present at the conference and to illustrate his talk with his striking images. Truth forces me to confess that Tamio stole the show with his wit and with his wonderful stories of his civil rights days—the rest of us on the panel were quite overshadowed.

I think that my favorite moment with Tamio was our evening together in January 2015. While usually we would all go out to eat, this time he and Mayu invited Heng Wee and me to dinner at their home in Vancouver. It was a small apartment located in a housing complex near the city’s historic Chinatown. Books and Tamio’s photos were piled all around in cozy disorder. Tamio and Mayu made delicious Japanese food. We sat around with them and their other friends, and talked and laughed. I had a delightful time. I recognized that it was the first (and so far only) time that I had ever visited a private house in Vancouver, or eaten a home-cooked meal there. By the same token, I realize now that while I had met and liked a number of Canadians of Japanese ancestry, Tamio and Mayu were the first ones whom I thought of as real friends.

The last time I saw Tamio was in January 2017. Fittingly, we went out for ramen in Vancouver—Tamio and Mayu were impressed by a newly-opened restaurant near their house. It was just before Donald Trump’s inauguration, and at first the mood was a bit somber, but as we ate and enjoyed the food and conversation, the mood lightened. Once we were finished, we went for coffee and dessert at a café nearby. Tamio told me that he was in negotiations to turn over his photo collection to an archive. I knew that it would entail an enormous effort of packing and classification, but I was glad that the photos would be preserved and publicly accessible. I was taken by surprise by the news of his sudden passing a year later, and felt a real sense of loss. Although the man has passed away, I continue to feel his legacy, both professional and personal.

© 2020 Greg Robinson