In 2019, the era name "Heisei" ended in Japan and "Reiwa" began. The 31-year Heisei era almost overlaps with the history of Japanese workers from South America coming to Japan. During the bubble period in the late 1980s, in order to solve the serious labor shortage problem in the manufacturing industry, the government revised the immigration law to allow second and third generation Japanese from South America and their spouses to work in Japan without restrictions. At that time, the economy was sluggish in many Latin American countries, with high unemployment and poverty rates, and in Peru in the 1980s, guerrilla terrorist activities were occurring. I remember that in my home country of Argentina, there was hyperinflation of 5,000 percent per year, and the average monthly salary in the local currency, the peso, was around 250 dollars in dollar terms. And the average monthly salary in Brazil and Peru was even lower1 .

Meanwhile, in the early 1990s, Japan's bubble economy was beginning to decline after its peak, but we didn't even notice any signs of this. I came to Japan as a government-sponsored student in April 1990, and I remember thinking that the economy was booming, something I had never experienced in Argentina. Japanese workers in Argentina were earning at least 300,000 to 400,000 yen a month, and many companies provided apartments and shuttle buses free of charge at the time. Remitting 200,000 yen meant that families back home could live comfortably for at least six months to a year.

However, Japan after the bubble burst is also called the "lost 20 years," and there is no such comfortable life. Thirty years ago, Japan had a total population of 123.2 million (now 126.7 million), a nominal GDP (gross domestic product) of 420 trillion yen, the second largest in the world (now almost 557 trillion yen, making it the third largest in the world), and an average nominal income per capita of 3.4 million yen (now 4.4 million yen). Due to the influence of the bubble, the national average land price was 480,000 yen per square meter, and in Ginza, the unit was tens of millions of yen. The media and investors proudly reported that Japan's valuation was four times that of the United States.2 Currently, the land price has fallen to 200,000 yen, less than half of what it was at the time, but I doubt whether the assets are actually worth that much. In addition, the national debt has increased from 254 trillion yen to 1,100 trillion yen, and in terms of GDP ratio, it has risen from 61% to almost 200%. On the other hand, if we look at the internal reserves of companies, they have increased from 160 trillion yen at the time to 460 trillion yen today, which shows that companies are saving these funds for various reasons and not releasing them into the market. Some point out that because the funds are not being used for investment or wages, this is preventing increases in wages and improvements in working conditions.

The university enrollment rate has risen from 36% to 58%, but tuition fees have almost doubled in the last 30 years, and the steady decline in the quality of university education and students is a major cause for concern. Also, the number of cars owned nationwide at that time was 30 million, and it has doubled since then, but young people, especially in urban areas, do not need cars as much, so new models do not sell as well as they did before.

The population growth rate in 1990 was 0.33%, and it was already showing a downward trend. The fertility rate has also fallen from 1.54 to 1.42, and there is no prospect of any measures to improve the low birth rate. The population aged 65 and over was 11% of the total population at 13.21 million, but now it is 26% at 33.38 million. This is 2.4 times higher than 30 years ago, and if things continue this way, it is certain that we will become a super-aging society. In fact, the life expectancy of men in 1990 was 75.92 years and that of women was 81.90 years, but has now increased to 81.25 years and 87.32 years, respectively. The current social security system will eventually be unable to cope with this, and considering the burden of medical expenses and pensions, these are figures that we cannot be happy about as a long-lived society.

Looking at the overall picture of Japanese society, the population movement to urban areas, where infrastructure is well developed, convenience is high, and high-paying jobs are concentrated, is accelerating. In recent years, more and more university graduates are seeking employment and life in their hometowns, but it is also true that the population is concentrated in commercial and industrial areas of Tokyo, the Kanto region, Kansai, and Tokai. Meanwhile, especially in urban areas, the trend toward nuclear families is also increasing, with households consisting of one or two people now accounting for 58% of households, up from 41% 30 years ago. In particular, the number of people aged 65 and over living alone has quadrupled, and 70% of these people are women.

As for young people, the average age at first marriage in 1989 was 28.5 for men and 25.8 for women, but now it is 31.1 and 29.4, with people getting married later in life. The rates of unmarried people, divorce rates, and remarriage rates are also on the rise, especially in urban areas. Looking at the number of international marriages, there were 22,000 cases (3.2% of the total) in 1989, but by 2008 this had risen to around 37,000 cases (5.1% of the total), and has now fallen to 21,000, or 3.3% of the total.

Over the past 30 years, Japan's economy has gone through repeated periods of stagnation and limited recovery, and looking at the numbers, we can see that Japanese society has changed significantly from 1989 to the present. Previous standards and assumptions no longer function as expected, and the working generation is feeling anxious. In particular, some foreigners living in Japan are wondering whether to stay in Japan permanently or spend their retirement in their home countries.

Peruvians and Brazilians who have lived in Japan for a while, including myself, can't help but compare the current situation in Japan with that of our home countries whenever we go back home. Although many things have improved, when we see the worsening security situation, political instability, unreasonable daily life, and intolerable injustice, we often feel that Japan is our home. In particular, this feeling seems to become more certain for many people when they start a family and their children start receiving education in Japan. In fact, prices in Japan are low due to the effects of a long period of deflation, so as long as you don't have a large amount of debt, it is possible to live a richer life in Japan than in South America. There is also a social security system that does not exist in the country of origin, so you can feel a certain sense of security.

However, even large companies with sales of over 10 trillion yen, such as Toyota Motor Corporation, which has sales of 30 trillion yen, are losing their international presence. The cutting-edge digital commerce and payment systems of the US-based GAFA (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple) and the Chinese BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) are global in scale, with the annual sales of these seven companies totaling 90 trillion yen and their market capitalization (shares of issued stock) equivalent to the GDP of Japan and the GDP of the entire Latin American nations.3 These new corporate forces will also have an impact on the Japanese economy, and there may be an increased risk of non-regular employment becoming more unstable in manufacturing and service sectors where Japanese workers are employed. The same concern is looming for young people in Japan in the future.

Latin American countries have prospered considerably over the past 20 years thanks to soaring international prices for mineral resources and grains. In many countries, including Brazil, a new middle class has been born, consumption has expanded, and infrastructure has been developed. In some countries, the average income per capita has tripled. However, most of the wealth is concentrated in the top few percent of the wealthy, and economic disparities have actually widened. It is also true that rising prices have made life difficult for many residents, and in many cases middle-class households have fallen to the lower classes. When international prices of major exports fall and global demand decreases, consumption in the country's economy stagnates, and the country falls into recession due to budget deficits.

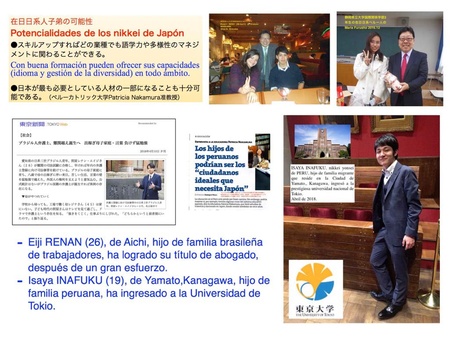

In addition, the rate of Peruvian and Brazilian children in Japan going on to higher education is gradually increasing. Although national or state universities in their home countries are almost free, it is not easy to pass the rigorous entrance exams and go on to higher education. In Japan, there are vocational schools and public vocational training systems, so if you have properly graduated from high school, you have a wider range of options than in South America.

Currently, there are about 250,000 Japanese South American workers living in Japan. It is the third largest Japanese community in the world after Brazil and the United States. To make it more likely that they will settle in Japan, they will need to understand the structure of Japanese society and the economy, learn more about themselves, and make an effort to use their diversity to benefit society while accepting the various changes and challenges they will face in the future. Of course, there are many concerns in Japan, but the same is true in Latin America and all over the world. Looking back over the past 30 years, the future will see more uncertainty and the pace of change may change, but the only way to pave the way as immigrant pioneers is to do so in such a social environment.

Notes:

1. At the exchange rate at the time, it would be 35,000 yen (27,000 yen at the current rate). Fortunately, the average annual income per capita in Argentina in 2018 was 1.2 million yen, 1 million yen in Brazil, and 770,000 yen in Peru, which is a significant improvement, although not sufficient.

2. The exchange rate in the early 1990s was 142 yen to the dollar, and in 2019 it is 109 yen to the dollar.

3. The total market capitalization of these seven companies is 560 trillion yen. This may change in the future, but it is surprising that this is the same amount as the GDP of 600 million people in Latin America. As an aside, China's GDP is 1,400 trillion yen, almost 2.3 times that of Japan. The United States' GDP is 2,200 trillion yen.

reference:

Office JB & Kazunori Asahi, Looking Back at the 30 Years of Heisei Japan through Statistics, Futabasha, 2018

Compiled by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, "Population Trends in Japan and the World 2014: Population Statistics Collection," Health, Labor and Welfare Statistics Association, 2014

CEPAL United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Statistics website

© 2020 Alberto J. Matsumoto