So can you describe leaving for Arkansas? That’s where you did your basic training?

Right, right. Oh yeah. There were lots of Japanese, Japanese Americans that went to Camp Robinson in Little Rock, Arkansas. And we went by train across the country. And it took us about two or three days to get there. And it was very nerve-wracking. We pulled shades down and went across the country.

Really, they told you to do that?

Uh huh.

Oh my goodness. It was like the same thing as all the other Japanese who were sent–

Well the train that we went on, all Japanese. And then we got off at Little Rock, Arkansas. But then I was surprised that there were so many Japanese. But we were all in college or graduating. We were a special breed, I think. I think they were going to use us for something but then somebody decided not to.

Oh okay. So taking all the college educated young men to maybe use for intelligence.

Intelligence or something, right.

But that didn’t happen.

No, that didn’t happen.

What happened when you got to Little Rock then?

Well then, there were 60 of us in this group, battalion. And we were divided into A, B, C, D. So we went to our respective camp. And I was in camp A and the others were B, C, D. And we never saw them and they never saw us. Except we’d go to Little Rock and we ordered fried rice. Then we would see them. “Oh there is so and so!” And some of us knew them and talked, “What are you doing?” “Nothing. We’re just picking up cigarette butts and keeping the place clean.” And same thing was happening to us. And then after a while, the draftees from other parts of the States came in and the group that came in in our area, in our “A” were from Minnesota.;

Were these also Japanese Americans?

No. Oh, I take that back. There was one Japanese American but he was a Caucasian Japanese mix but he didn’t speak any Japanese. [He was] very tall, very, you know, built strong.

So when it got kind of integrated with different people, did you face any discrimination?

No, I didn’t. But I guess they were scared [laughs]. And as we got talking, first they were surprised that we could talk English. We could do all the exercises with push ups, most of them were college or just graduated from college so they were used to all these exercises. So they could see short guys, like myself, hit the board and reach over, climb over, pull ourselves over and everybody was shocked that we could do all these things.

You were athletic.

Oh everybody, everybody.

So your job, what was like your job then?

Oh, then, we didn’t have any job description of what they are doing. What they going to do with us? We learned how to make tents and how to water, when it rained, how to make a hole so it would drain. It was sort of fun because I didn’t know anything. [laugh].

Yeah, you were probably making new friends, from all over.

Oh yeah. They were just surprised that there were so many Japanese in the regiment.

Now you said that some soldiers came to recruit for the 442nd.

But I think you mentioned most people refused to join?

Well there was only one or two that went. The parents were ordered to evacuate everything and they saw everything they had, gone. They had to sell this and they had to sell that. They didn’t have anything. So they were gone and nobody knew what to volunteer to this unknown.

Right. That must have been interesting when you heard what they were doing, after the fact, what the 442nd had done in Europe. Were you glad that you did not join?

Oh yeah, yeah. But the 442nd and whatever unit that sacrificed itself, we were very proud of their accomplishments.

Yes. Absolutely. Now, during this time, what happened with your family? Where did they go?

My family went to Poston, Arizona.

Ok. So everyone was there. But your brothers were —

They were no/no boys. Not that they were saboteurs or anything like that, but they just didn’t want — because the way it was written: Would you fight for the United States or something like that and the second one was would you fight the Emperor of Japan? And the first one was, they saw the evacuation, they lost everything so they were just mad. So they said no on the first one. And then the second one, that was no. So they were no/no boys.

Wow. But they kind of went beyond saying no-no to those two questions, right? They ended up in Santa Fe and Bismarck?

Oh yeah, they went all over the country. It was Santa Fe they went to and Bismarck, North Dakota and they went to Tule Lake.

Did something else happen in the camp beyond them saying no-no? Were they vocal?

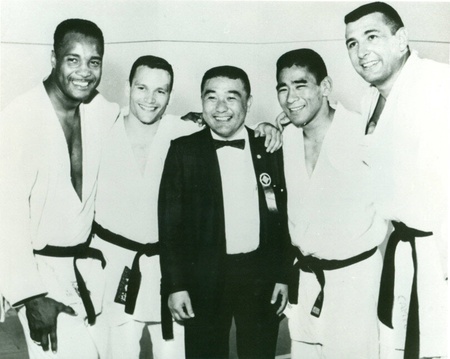

I probably would have said no/no, too. Because at that time, you can’t do anything. So they would, like my brothers, to kill time they would do judo with all the friends and all the guys that wanted to learn judo. They were judo teachers. And my brother was a very good judo teacher. Before the war if any of the teachers were ill, they would call him to cover for them all the way from San Pedro to Los Angeles to Hollywood.

Oh wow. Now was this Henry or was this George?

It was Sam.

Your eldest brother. Did your parents also move with them to Tule Lake?

Yeah, went as one family.

So your parents were there as well. Now did they all return to Japan?

They went back.

What year was that?

1945.

And your parents followed, too?

They followed.

And where were you when the war ended?

I was just getting ready to be discharged. And I was at Camp Crowder, Missouri.

Were you back in California by the time they left for Japan?

I got there, I got to California, they had already gone.

So did they tell you in a letter? How did you find out that they were deciding to go?

Oh my mother told me. She says she had to go back because of the two younger ones. She says she has to take care of the two younger boys. And I told her, “Don’t go. Stay here.” In later years I appealed in a letter, “Come back.”

So they left. You didn’t even say bye to them?

You just found out. Can you describe what your brother did though while they were in Japan? You said he was a liaison?

My oldest brother helped Nikkei people that came back because they came back but they had nothing, or they couldn’t do anything because they didn’t have any jobs, and they were sort of also discriminated in Japan. So my brother, Sam, because he was bilingual, he talked to the Army and told them that these people needed jobs. And the Army said, “Oh, sure” because they needed somebody, too. My brother would help get the Nikkei that came with him, place them in a job.

And my younger brother, he knew something about auto mechanics. So he introduced all the Japanese people to the place where they had a lot of cars that had to be cleaned out. So my brother George helped many of them get jobs. So he was a hero in Japan.

So they did pretty well then because they had that language skill.

Yeah. So they didn’t really suffer as some of the other people.

It’s kind of a good thing your parents wanted you to learn the language.

Yeah. And then things changed and there’s a Supreme Court ruling that you can’t send people to any place because of their, because they said no/no. Because they were born here, the United States was responsible for them, for the people that went back to Japan. So, Henry came back, finished at UCLA and George came back and he went to San Jose State, graduated and got his Masters from there and taught school.

And your parents? You said your mother was able to come back.

Yeah I asked a Congressman [from the] South Bay. He was a congressman from Gilroy. I went to see him and he said, “Sure, no problem,” and he wrote a letter and she was able to come back.

Wow. Now did your father pass?

He passed away.

So you came back to California — how did you pick up your schooling again? And how was the resettlement for you?

Well it was not good. I figured well, I spent four years, got an honorable discharge, I was going to come back to San Jose because everyone said San Jose is a good place because it has a lot of Italians. And they’re much more receptive to having Japanese. So that was another reason I came back.

And did it turn out that way?

Well I don’t know but the Italians I knew were very nice. I came back end of 1945, December I got discharged. And because my daughter was ill, instead of taking a train we flew, so all my discharge money that I got — I think about a couple hundred dollars — went out the window. Because I spent every cent I had for all three of us to fly to San Jose from Kansas City, Missouri.

So when did you get married, before the war?

1943. I was already in the service.

And where did you meet your wife?

She was at San Jose State. I didn’t see her too often but when I did see her she was going home. I was going to school. I said, “Hey, where you going?” and she said she was going home. I says, why? “Well, my instructor told me that I can’t get a job because I won’t be able to be a student teacher.” She didn’t have the experience, so she might as well quit school. So she quit school, went home. But later on, when she was in camp, she taught in second grade and the Japanese American National Museum honored her at one of the dinners. She was very happy that she was recognized.

Yes. And where was she in camp?

Poston.

Oh, Poston as well. So you came back and you resettled in San Jose and just started rebuilding your life. Now how did judo come back to be your main focus?

Well, I was lucky when I signed in and school started. The man who was in charge of Tule Lake came to see, I guess he must have come to see all these places where people were coming up with no/nos. My brother was unusual then because he spoke both Japanese and English, bilingual. And Japanese people would ask him to do something,

I’m curious about you making judo your life, and you have this legacy.

It really is not my life.

For your legacy though, a lot of people think of you as the epitome of San Jose judo. How do you feel about that?

I felt that it had to be — we have to go back a little bit. You see, you had lots of people that were drafted and people were taught judo by people that just had a [small knowledge] of judo. You just can’t teach a group like that. “Now this is the way you throw somebody or if somebody comes at you, you pick them up and threw them.” Judo got kind of a bad name because after the war, there were so many people that got injured. They didn’t know how to fall or anything. The persons that got hurt were people that had no knowledge of judo and their brothers and sisters or friends were going to the Army and they came back with a [bad] technique and really hurt themselves. You know if you throw someone in the air you’re gonna put your hand down the wrong way and you break their elbow, or finger or shoulder. And those are a lot of injuries. So judo got started with, “Oh don’t take judo.”

“It’s dangerous.”

Dangerous. So we had to correct all that, and make sure they did the right thing. Many many injuries were caused by people who had no knowledge of judo, just trying to show somebody judo and they’d get hurt. But in ours we went very slow and they worked on the mats a lot. By a lot I mean the mat technique, lying on the floor. So they moved around and showed them mat techniques more than throwing techniques. So after a while they were not scared of the mat, they knew how to fall.

So you kind of saved the reputation.

Oh yeah. We started to be very careful about it and moved judo forward that way so that people that didn’t know judo, we could teach them. And we had to teach teachers because without teachers you can’t [learn]. So a lot of students, most of them were graduates of San Jose State and they had class under me and spread out.

Now I’m curious going back to the legacy of the war — did you receive redress?

Yeah I got redress.

When you received it, what was your feeling about it?

Well, I felt really, I wasn’t supposed to get it but I wasn’t going to refuse [laughs].

Did you feel a sense of closure?

No, no, no. No it didn’t make closure, that was something that was — the Japanese Americans deserved it. They gave us a little bit of a start to push forward.

What are your thoughts on what this experience was for your parents?

Oh, it was bad because they came without too much knowledge of the United States and they had to move. They leased the land and then they had to move almost every three years. And if the crop was good they made some money. The Depression in 1930 was really bad. And things that we grew — a field full of cabbage, there was no buyers. So sometimes county welfare would come and they would say you want to cut those cabbage? We’d say no. They’d say, can we have them? We’d say sure. And maybe a dozen guys already on the truck and they would get out of the truck and the truck would go through the field and they would pick cabbage and throw it in and fill it up, take it home. But we just gave it away because we couldn’t sell it.

And that time, my parents would have no money to pay for the groceries or anything. And it was called Stanton Grocery, both of my parents would go there and they would say that they would pay sometime later and never had any money to pay for it. And this went on for quite a while but eventually my parents were able to pay them back. But I found out later that other parents too were really surprised that the grocery store remained open.

Do you have grandchildren?

What kind of lesson do you want them to remember about your life experience and this experience of WWII?

Well, I like to have them know about it, where they’re from and what happened to their grandparents. And how hard they had to work so that they have equal rights with everybody else. And those are things that to every Japanese American, I hope they recognize. That’s what I hope we can do.

*This article was originally published on Tessaku on March 14, 2020.

© 2020 Emiko Tsuchida