I started volunteering at the Japanese American National Museum in 2000. I immediately took advantage of one of their services—access to the National Archives WWII War Relocation Authority (WRA) records through the Museum's Hirasaki National Research Center. The WRA was a U.S. government agency formed to handle the incarceration of people of Japanese ancestry under Executive Order 9102, from March 18, 1942 until June 26, 1946.

First, I looked at the WWII Individual WRA form #26. The form was an individual record containing basic information—name, family number, birthdate, birthplace, address prior to removal, occupation, education attainment, language abilities, and ties to Japan—for the roughly 110,000 individuals who entered one of the ten WRA Relocation Centers.

I thought that this was strange; why wasn't WRA-26 numbered WRA-1? This led me to track down the WRA-1 form, which I eventually found. I also found other WRA forms, most of which were numbered above WRA-26, but I could not find WRA forms between #2 and #20. The question was, why not?

I found the background on WRA-1. My research led me to what I felt were possible additional, broad historical reasons that the U.S. Government systematically orchestrated the incarceration of people of Japanese ancestry beyond the three reasons (racial prejudice, war hysteria and failure of political leaders) that the 1980 Commission on Wartime Relocation and Interment of Civilians came up with.

I was able to piece together other bits of information and came to the conclusion that one possible reason to move people of Japanese ancestry into the inter-mountain states during WWII was to meet the agriculture labor shortage, due to the military draft and the need for factory workers. I discovered that Idaho and other inter-mountain states asked for more field workers because the government lifted the sugar beet acreage quota that was used to stabilize the price of sugar. Idaho farmers were asked to double the acreage to 100,000 acres of sugar beets, but they only planted 85,000 acres because the farmers felt they might get enough workers for the 100,000 acres. In late April or early May 1942, the sugar beet farmers and the sugar beet companies asked the government to release the Japanese American evacuee farmers and farm laborers who were removed from the Western Defense Command (WDC), which was made up of 108 restricted areas in the country's West Coast. My father was one of 10,000 evacuees who were given permission to leave the War Relocation Centers in the Fall of 1942, to help save the 1942 sugar beet crop.

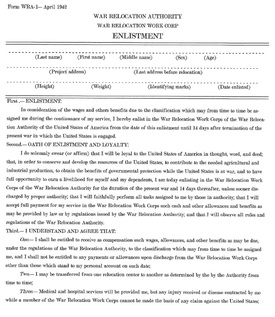

This brings me back to the WRA-1 form. The War Relocation Work Corps program recruited workers for the government to be used as they saw fit. Families who volunteered could be separated and sent anywhere, at anytime. The evacuees saw the flaws in the program's contract and thus, refused to cooperate, so the program closed in 1942.

It was replaced by a Short Term Leave Program that required an application form to be filled out, find an employer and a place to live, and clearance by the FBI. It granted the evacuee permission to leave the WRA Center for the 1943 spring beet thinning, summer weeding work, and the fall harvest of potatoes and sugar beets. The evacuees were then required to return to the WRA Relocation Center for the winter season.

The WRA forms that I was able to find are in a binder in the Hirasaki National Research Center at the Japanese American National Museum.

© 2020 James K. Tanaka