Did your parents ever have any conversations with you or your siblings about what was happening?

Well, see, my mother and father spoke Japanese at home. But when my mother spoke to us, maybe before the war or camp, she might have spoken to us in Japanese because Papa insisted on us speaking Japanese. But once we were in camp, it was the Japanese way. “Nihogno hanishitaku nakata.” (Didn’t want to speak Japanese). Pound your fist on the top of the table “No, no.” My father had a loud voice, so I remember coming out of camp and if we went somewhere, I would tell Papa, “Not too loud.” I didn't want people to know we were Japanese.

So that's how much language interrupted our whole way of life. Our cultural being. It's hard to understand. And I have met [people] at these pilgrimages. A five year old kid who is playing his father came to get him and the father talked to him in Japanese. He was embarrassed to hear Japanese from his father. And he went back later and told his father, “Don't talk to me in Japanese when you come after me in front of my friends.” I've never heard that before. And you can’t imagine somebody being that [way] about our language, being self-conscious, embarrassed. But, you know, it's funny. I don't think about it anymore now. Now it's almost a gift. Speak multiple languages, they look at it very differently. It's a benefit versus a detriment.

What do you remember about Tanforan? What were your first impressions?

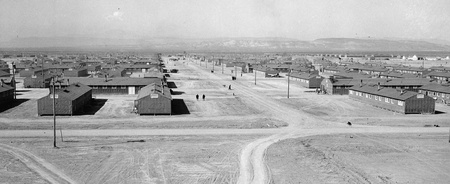

Hardly [any]. We were there for only three, four months. But I remember parts of Topaz.

What do you remember about Topaz? Did your parents work in camp?

My father was a cook. We went there in October of ‘42. So the summer of ‘43, my uncle was farming in Montana. So my father went to work there, too. But having four kids at home, he couldn't leave, you know, stay away for too long. But also, there was a way of saving money, making money, because once we came out of camp, we found the place to farm and to pull the trees out, hire people. He needed the money. And my father had a very friendly person who looked after his tractor farm. And we had a passenger car, ‘37 Ford. Mama would drive us to drive-in theaters and stuff. Still remember.

So all of your possessions were safe?

Somebody looked after it. You hear so many stories of people losing things because they were vandalized, or stolen. My father was so lucky.

Do you remember coming back after Topaz?

Completely. I remember. My father, we had this tractor and he would do tractor work for all of these flower growers. There was a friend of ours who grew orchids. He had a glasshouse. So Papa had very good friends from the Block 16 of Topaz who settled in Walnut Creek. So Papa right away said, “Oh, you should go work for these Okumuras, who have a house for you to stay in and work in.” They would grow this variety of flowers, orchids were quite hard to grow. It wasn't quite warm enough. Winters would be too cold for orchids they were grown mostly in Hawaii or other places.

I had two older sisters who owned property and one owned the grocery store. And as soon as we came out of camp, they bought a grocery store in Mountain View called Capsule City Market. People who lived in Mountain View would know it because they sold Japanese goods [in] 1946, ‘47. When we were farming in Palo Alto, they bought the store.

Did you experience any kind of backlash coming back or was it more or less welcoming?

Palo Alto is a place where it was hard to find or rent homes or buy homes in certain areas. But because we found this piece of property right next door to Stanford University, part of where Stanford Industrial Park became. Most of our neighbors, we found one 20 acre piece of land, we farmed it for two years and then he wanted to sell it. And so we found another 20 acre piece of land. So for us to find these land where you have to pull out the trees or clearing and things that you have to do, there's a lot of hard work preparing land to just actually really farm. Somebody was maybe farming it, but it was haphazard. It wasn't really a farm. And when Papa wanted to grow something, he wanted to make sure he grew it right. He was a true Issei. And then we found a place to farm in San Jose.

And you owned that land?

That we bought.

Wow. So that must have felt good for your parents to finally own land.

We moved into a brand new house after living in these shacks. That was on the property. The house wasn't lived in for ten years, but we had to make it livable. And so Papa’s older sister came to help us and Papa’s next oldest sister’s sons helped us. When they bought the grocery store, sons would take time when Papa needed somebody to drive his truck. We raised beans so they were canning beans. So we had to drive to the cannery to deliver the beans every afternoon or early evening.

So he worked all the way ‘til my brother bought a place out in San Martin. My father would go there every day to plant tomatoes. And that was his specialty. We farmed quite a bit of acreage of tomatoes. And so once we incorporated, we again sponsored this [JAMsj’s rotating exhibit sponsored by Mune Farms] for me to honor my brother because without him, you know, everybody left the farm. Kin wanted to stay and become the farmer.

And when did you sell the property?

We just leased the land first. And then on Morrill Road we bought it in 1950 and sold it in ‘67. And then we had to sell it to buy this place where we strictly built a packing shed for the tomatoes. And then we had to build these two big coolers 30 feet by 40 feet. We had to pre-cool the tomatoes to be shipped back east. So we had a broker who sold our tomatoes. In fact, people would say, “You became the biggest tomato farmers in Santa Clara County.” Sizing machines was the number one thing we had to have. We couldn't hand size it anymore.

So that was another reason why I wanted to do this, for Kin's sake, who was dying of mesothelioma. We had this opening in February and Kin couldn't come. It was too cold, he was quite frail. And he died in August.

But he knew of the impact of his story and the family name.

Oh yeah, at that opening, I wanted to talk about Kin. When my brother decided that he was going to be the true farmer and for my youngest brother and myself to join, I think my father was so happy.

Were you closest with him?

You know, we weren't really. We had such different attitudes. I became a traveler. When I left one summer, because my brother-in-law joined the farm, we didn’t get along. So it was a good excuse. So I took off for Europe and I was gone for four months. I had a three month Eurail pass to spend time in England. So when I came home in September, Kin picked me up at the airport. That was one of the last years, and in ‘76 [he] bought a nursery. It's in Union City now. But it was the Frank Ogawa nursery who became mayor of Oakland. That was his nursery. He did not work that hard to maintain and run a nursery. So Kin expanded it and he actually he started two businesses. And I now think about, gosh. How hard he worked, how he was just good about, you know, the Nikkeis or Niseis. They worked hard.

And he's never talked about money. But because I had no place to stay. So when I was going through Mexico, I was there for about four or five months. But I came home just before Christmas because Kin was dying of mesothelioma. And so my niece wanted somebody to stay in her house. She has a little one room granny's house in the back. Well then Kin said, “Come and live with us.” I said, “Kin. You know, I want to pay you rent.” First time I heard him say “I have a lot of money. You don't have to.” But I miss especially the last four months when Kin was sick.

Do you get nostalgic sometimes to see that nothing here in San Jose is farmland?

I didn't mind leaving the farm after 40 years. You work on a farm, you're sort of glad to be like this (makes hand dusting gesture). Dusting your hands off to that hard work.

And how about your parents — did they pass away by the time the redress was given out?

My father died in 2001, three months before 9/11. He lived till he was 97.

So he received his apology and redress. Do you remember his reaction to that?

Oh, he was so happy. He kept asking me. I was sort of working on the redress or reparations committee. I said, “Papa, we'll get it. We'll get it.” He couldn't believe it. And finally, the day we received news of President Reagan signing the apology letter and they had a function at the Issei Memorial building right next door. And Papa was the only Issei there. I was so proud of him. “Papa, let's go. We're gonna celebrate because I told you, Papa, we're gonna get the money.”

Papa and Mama never talked of any bitterness of camp. Never talked down about the white people. But he always said, “Just work harder than them and you'll be better than them, mentally.”

*This article was originally published in the Tessaku on April 15, 2020.

© 2020 Emiko Tsuchida