During the Second World War, George Doi and his parents and siblings were imprisoned in an internment camp at Bay Farm in Slocan. After they were released, Doi’s father started a logging business in the Slocan Valley. Later, he worked for many years in the B.C. Forest Service locally. In parts one and two of his series on the internment camp, he described the events leading to the internment, the family’s eviction from their home on Vancouver Island, and their temporary internment in Hastings Park, Vancouver.

Here, in the third of a four-part series, an 11-year-old Doi and his family are on the train, being relocated to the interior.

* * * * *

My memory of the train ride was an absolute blank. I vaguely recall being seated in the train and from the window saw telegraph poles whizzing by and hearing the clickety-clack along the tracks. I tried to block out all feelings of nausea and fell asleep. I cannot remember any part of our rail trip. But, if I were awake and enjoying the ride, I would have noticed the high mountains coming together as we approached the town of Hope. Then, following the Canadian Pacific line through the Fraser Canyon into Lytton and heading east, I would have seen the flat open Okanagan Valley, Greenwood, Grand Forks and Christina Lake. Continuing eastward between the narrow mountains we would come out at Farron (water stop) and the Lower Arrow Lakes to Castlegar and finally into Slocan Valley.

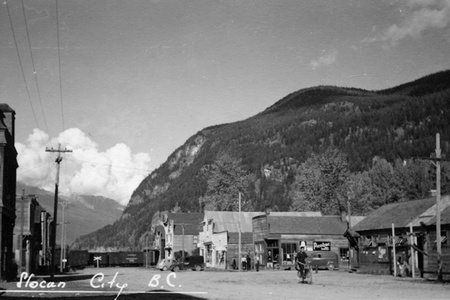

I still hadn’t got over my motion sickness and cannot remember our arrival to Slocan City but it should be safe to say that we did get off at the Slocan City rail terminal.

Popoff Internment Camp

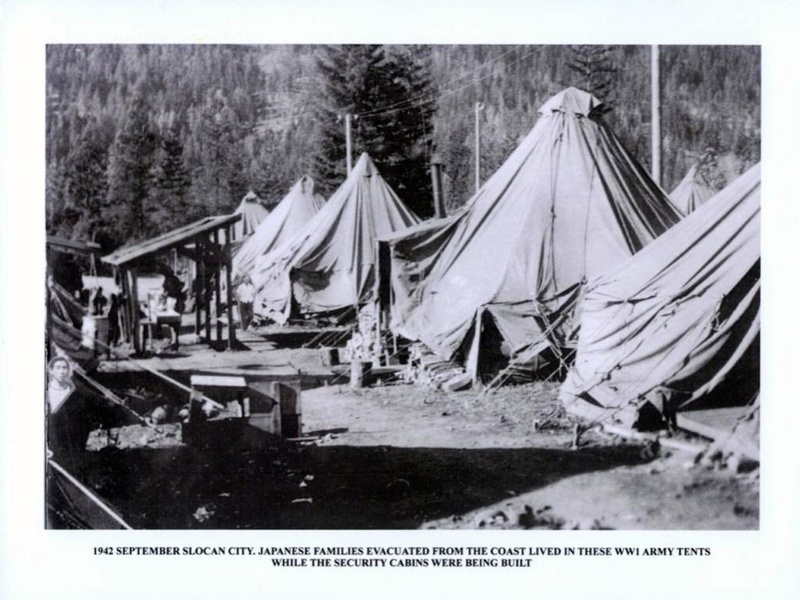

After we were checked off by the officials, we loaded our baggage onto a truck and were driven to a place called Popoff (an open field owned by Mrs. Popoff who was also into real estate business), about four kilometres south. Here we were booked into an army type wall tent to accommodate all eight of us. This was to be our temporary residence until our shacks were built.

I don’t know how I felt when we got to this place but had I been older I’m sure my thoughts would have leaned towards bitterness and I would have asked, “Why, what did we do wrong to be forced out of our homes to live out in this remote wilderness?”

I’m sure the question of why? why? why? would have stayed with me for a long time as we all had to struggle to re establish ourselves in this new environment and to cope with the ever-nagging question of not knowing our ultimate destiny.

Fall comes early in the Interior and within a few weeks everything started to freeze and the snow followed. Icicles were forming inside the tent and the additional clothes we wore to bed were not adequate. Every morning we got up very early and stood outside around the hot fire that we started in a tin nail keg.

Our meals were served inside the hockey rink in Slocan City, a three-km walk.

There were some tents set up inside the rink, probably for the kitchen staff. They sometimes served chocolate pie and egg custard and I always looked forward to these treats.

The Russian Doukhobors from Popoff and Perry Siding used to come on horse drawn wagons and by sleds in the winter to sell fresh vegetables like cabbages, carrots, turnips, etc. and they always had a gunnysack of raw sunflower seeds. They were a godsend because veggies weren’t in plentiful supply.

It was a common sight to see Doukhobor kids carrying ripened sunflower heads and tossing a few seeds into their mouths then spitting out the shell. I have noticed on television that many baseball players chew sunflower seeds instead of bubble gum to calm their nerves.

Bay Farm Camp

Mom told me that straws were drawn to decide who got to move into the next available shacks. We were lucky and moved out of the tent in Popoff before the long winter set in. Our house was at the far end of First Avenue, near the railway tracks. (Families less than six had to share the cabin with another small family and the common kitchen in the middle room.)

The dimension was about 14-by-24 feet, and divided into three rooms. This being our first experience in Interior winter, it was cold, very cold. Even the local old-timers mentioned it to be one of the coldest winters they had experienced.

As all the shacks were built with green lumber with roofing paper on the inside (some on the outside), it was like living inside a refrigerator in the winter. When the winds blew we could feel the cold drive through the walls and frost would build up between the boards.

The two end rooms were our bedrooms. I remember a single and a double bed crammed in one room but cannot remember how many beds were in the other room. The beds were made from two-by-fours and shiplap, and mattresses were filled with straw (or rags).

The eating area was even smaller. Quite frankly, I cannot remember what the table and benches looked like. But you could just imagine what it would be like to have 10 people in a 8-by-14 foot kitchen crowded with a table, two benches, a kitchen stove, a sink, some wooden boxes for shelves, pots and pans, and couple of water pails.

Of course it would be very crowded so in the morning, when it came time to wash and eat, we all seemed to know what to do without having to be told. Some got up earlier, or if the kitchen was crowded there would be last-minute homework or other things to do in the bedroom.

Later, we built an 8-by-10 foot addition on the back for storage and dug a root cellar under one end of the house. I also built a small shed from slabs that I scrounged and I kept pigeons in it.

The only source of heat was the kitchen stove in the middle room. Later, we installed a small tin heater and cut a hole in the partition to allow the heat to circulate, at least into one bedroom.

Of course condensation was forever a problem. Ice would form on the windowsills and almost every morning we would chip away the ice built up at the bottom of the door before we could open it. Even laying a rag across to stop the draft didn’t help. By morning the rag was soaked and frozen. With 10 people crammed into a small quarter, I honestly don’t know how we ever managed to live through it.

Water was the other commodity that was precious to us in the winter. Outdoor water taps were located every three or four houses apart but most of the time the pipes were frozen and water had to be trucked in. Fortunately we lived close to the river so we packed our water from about 500 feet away.

The British Columbia Security Commission was in desperate need of places to relocate us but none of the communities (except Greenwood) in British Columbia and the rest of the country wanted Japanese Canadians. They finally found sites to build camps in the Slocan Valley and to house the rest in abandoned building that were becoming ghost towns. It is a narrow valley between two high mountains. There is only one road leading out to the south and similarly to the north. Thirty-seven kilometres north of Slocan City at New Denver was another internment camp and also at Sandon and a small camp at Rosebery. Here again lakes block the lone road out to the north. We had done no wrong so what reason was there to run away?

I think I’m right in saying that our activities were basically confined to our own camps and there were very little intermingling between them, other than school sport days. There was probably not the need to visit as both adults and children were always busy and didn’t have the wandering minds to go and see more camps.

In Bay Farm camp we shopped at Mr. and Mrs. Hurst’s grocery store (they had all their veggies displayed on the floor in gunny sacks) and at Bob Albright’s Grocery/Meat Market. A little later there was Taishodo Drug Store. Slocan City was only one to two km away so some walked there to shop. Some things like tea, coffee, sugar and chocolate bars were rationed so purchases were limited using coupons.

One of the first things the adults did was to build a school so that their children wouldn’t get too far behind in education. (Teaching in Canadian Exile by Frank Moritsugu is a worthwhile read.)

Our school in Bay Farm was called Pine Crescent School. It burned down in 1945 or ‘46. The government then allowed us to go to the regular local public school in Slocan City. To accommodate all students a church and Legion Hall were used for junior and senior grade kids.

Other camps

Lemon Creek Internment Camp was built on an open field eight km south of Slocan City. This was biggest camp in the Slocan Valley that held approximately 2,200 evacuees. Here the men were making eight-foot hewn ties with double-bitted axes for the railway.

New Denver and Rosebery Internment Camps were located at the north end of the Slocan Lake, a beautiful setting for the camps that housed together 1,500 evacuees.

Tashme Internment Camp, the largest of the internment camps, was just 17 km east of the city of Hope, and held about 2,600 Japanese Canadians.

Situated in a remote area with no shops or public conveniences nearby, the adult internees sensed inevitable problems with such a large crowd. They immediately organized various committees like Social, Education and Media and kept everyone busy and informed. I heard they even made soya sauce and miso in the camp.

Other internees were placed in abandoned buildings in Sandon (900 evacuees), Kaslo (1,000 evacuees), Greenwood (1,200) and Slocan (1,000).

Also, over 1,100 Japanese Canadians voluntarily left the coast to self-supporting places like East Lillooet, the Caribou and the Okanagan.

About 4,000 went to work on sugar beet farms on the Prairies, 2,000 worked on road construction in the Rockies, and about 700 were imprisoned in Petawawa, Ont.

To be continued...

*This article was originally published by the Nelson Star on May 21, 2017.

© 2017 George Doi