We know that Japanese people are living all over the world these days. But when we see or hear about these immigrants and settlers on television programs, we sometimes feel simple questions and surprises, such as "Why are there Japanese people in places like this?" and "Why is this person here?"

For me, the first such example was when I learned about the Japanese colony (village) that once existed in Florida, USA, and the people who gathered there. This was in the 1990s. Everyone knows that Japanese people immigrated to the Pacific coast, such as California, and that there are many Japanese people there, but I was surprised to learn that there were Japanese people who had settled in Florida, the southernmost state on the Atlantic coast, the furthest from Japan in the United States, during the Meiji period.

Furthermore, the colony was dismantled before the war and most of the settlers left the area or returned to Japan, but one man who remained until the end donated the land he had bought up to the local area, and this led to the establishment of a magnificent Japanese garden and museum in South Florida.This fact provoked my imagination, and I wondered if there must have been many dramatic events behind it.

I had the opportunity to do a sort of internship at the Daytona Beach News Journal, a local newspaper based in Daytona Beach, a city on the mid-Atlantic coast of Florida, for a year from 1986 to 1987. At that time, I had never heard of Yamato Colony, and I had no interest in finding out.

I chose Florida because it seemed like a place with little to do with Japan, and I wanted to experience grassroots America, so I didn't have any interest in anything Japanese. However, when I visited Florida again a few years later, I learned about the existence of the colony, called "Yamato Colony," and the man who donated the land, Morikami Sukeji, and became interested and started researching it.

In Americamura, Wakayama Prefecture

It all started with a simple question: "Why are there Japanese people in a place like this?" At the same time, looking back, there was a trigger that sparked my interest in Japanese immigrants around that time. One of those triggers was an experience I had when I visited the seaside town of Mihama in Wakayama Prefecture for a piece of research.

The Mio district of this town was known as "Amerikamura" (American Village). In the past, many people from Mio immigrated to Canada, and those who were successful in fishing cooperatives and other organizations returned to Japan and built Western-style houses, so it was called that because they were American. I learned this for the first time when I was there, and by chance, while reporting in the town, I met a Japanese-American family who had come from Canada to visit their hometown of Mihama-cho, and they told me their family history. It sounded like a dynamic story that transcended time and space.

Returning to Florida, Morikami Sukeji, whose name was given to the "Morikami Museum & Japanese Gardens" after the Japanese man who donated the land, was from Miyazu City, Kyoto, famous for Amanohashidate, one of the Three Most Scenic Spots in Japan. When I inquired about Morikami at the Miyazu City Public Relations Office, the person in charge kindly sent me some documents. Among them were a couple of copies of books or printed materials that described Morikami Sukeji in detail.

The language is old-fashioned and old kanji characters are occasionally used, so I guessed it was written quite a long time ago, but it contains detailed information about Florida and Japanese people living in Florida, including Morikami Sukeji, along with many names. I wondered what the original was, so I looked it up and found out it was "America Nikkeijin Centennial History - Zaibei Nikkeijin Kaihatsu Jinshiroku" (published by Shin Nichibei Shimbunsha in 1961).

1431 page book

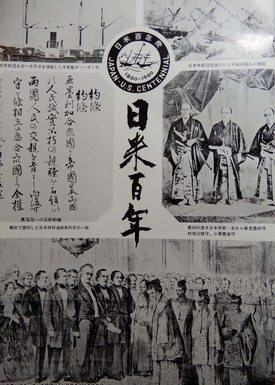

I live in Kanagawa Prefecture, so I went to Yokohama Central Library, which I knew would have this kind of book in its collection, and I was able to find it. It's a 1,431-page book like the Kojien dictionary, with 25 lines in two columns, 37 characters per line, and is crammed with text. It was published to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the establishment of amity between the United States and Japan, and contains pages of black-and-white photographs of commemorative events, including a photo of the Emperor and Empress visiting the United States in 1960, as well as prefaces by then Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda and the Japanese ambassador to Washington.

The main part of the book is "Part 1: A 100-year history of Japanese Americans in America, General Edition," which takes up just under a quarter of the book, followed by "Part 2: History of the Development of Japanese Americans in Each State, Regional Edition, Included: Records of People Developing Japanese Americans in America," which describes the footprints and activities of Japanese and Japanese Americans in each state. About half of it is devoted to California, and I was surprised to see the detailed records of Japanese footprints in even the smallest states.

I really wanted to have a copy of this, so I looked for a used copy online, but I refrained from buying it because it was quite expensive in Japan.However, I found a reasonably priced copy on the website of a used bookstore in San Francisco called Bolerium Books, and was able to purchase it.

The details for each state are covered in detail in “ Rereading the 100-Year History of Japanese Americans in the United States, ” a series published in Discover Nikkei from 2014 to 2015, so this will be a bit of a repetition, but for Florida, for example, the explanation is as follows:

"The Japanese immigrated to the area after the Florida East Coast Railroad was built from Jacksonville to Miami in 1896. (Omitted) The railroad company planted pineapples on part of two sections of its land (1,260 British and Canadian) located 40 miles north of Miami, halfway between Bocaland and Delray Beach. However, they were unable to compete with the cheaper Cuban produce, so they announced that they would offer the land to the Japanese, hoping that they would bring in Japanese people who were skilled at growing vegetables on the Pacific coast to grow winter vegetables.

Masakuni Okudaira, the younger brother of the lord of Nakatsu Domain in Buzen, Kyushu, and Jo Sakai (from Miyazu, Kyoto) heard about this while studying abroad in New York and both entered the area in 1904. This was the first time that Japanese people set foot in Florida.

In this way, the first Japanese to settle in each state is written, and so far as is known, the footsteps of Japanese people in the United States are written up until around 1960. In addition, the book focuses on individuals and compiles biographies of them to a greater or lesser extent, and introduces various episodes related to the Japanese community, including disputes, incidents, accidents, and other scandals.

Photographs are also inserted here and there. It is not an academic book that lists references, nor is it a book that builds an argument based on a few facts, but it is packed with specific facts and information that make you feel like it was written on foot after extensive research.

According to the colophon, the book was published on December 25, 1961 by New Japan and America Publishing Company in Los Angeles. The publisher is the company's president, Saburo Kido, and the editor, Shinichi Kato, is listed first.

I was drawn to this book, which can be read as a multi-generational story of the countless Japanese who came to America, and I wanted to know first of all how it was created. Kato gives a clue to this in the afterword of the book, which was also surprising. It seems that Kato alone traveled around the United States to gather information and compile the book.

(Titles omitted)

© 2020 Ryusuke Kawai