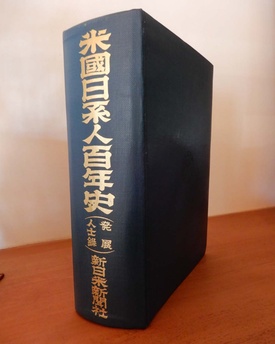

In 1960, a man drove around the US to follow in the footsteps of the first generation of Japanese immigrants. At the end of the following year, Kato Shinichi (then 61 years old) compiled his account of his experiences into a book called " A Hundred Years of Japanese Americans in the US - Chronicles of Development " (Shin Nichibei Shimbunsha). Originally from Hiroshima, he moved to California and became a journalist in both Japan and the US around the time of the Pacific War. Although he himself escaped the atomic bombing, he lost his younger brother and sister, and in his later years he devoted himself to the peace movement. We follow the energetic path of his life, which spanned both Japan and the US.

* * * * *

The difficulty of following someone's life

I have tried to trace the life of a person many times in order to write non-fiction, but it is not easy to clarify the life of an ordinary person, even if they lived after the Meiji era. The life of an ordinary, nameless person becomes surprisingly unknown once the person and their family pass away and a new generation comes along.

Apart from people who come from old rural families where they have lived in the same place for generations and where the family history has been passed down, most people change places and jobs often, and in Japan's housing situation, there are usually no relics left behind that tell the story of the history of their parents, let alone their grandparents. Children and grandchildren also rarely hear about their grandfathers and parents' lives. It is common for descendants to hear about the personalities and lives of their predecessors and predecessors from others and find it relatable.

Looking back at myself, I don't really know what kind of people my father and mother were when they were young, or how they lived. Looking at my friends and acquaintances around me, I have hardly heard anything about their lives from their grandparents or parents. Especially during the war, I imagine there were many painful experiences that they didn't want to talk about. When people listen to stories from their parents' past, they are not interested in them when they are young, and by the time they finally begin to understand the meaning and significance of history, their parents are often no longer alive or their memories have faded.

However, it goes without saying that, in general, to know a person's life, their relatives will know them best, so start by listening to their stories. Next, look for friends and acquaintances if they may still be alive. Other methods include looking into the places where the person lived, the companies where they worked, and records related to the jobs they were engaged in, in order to clarify the circumstances surrounding the person. This is the process of filling in the gaps.

With the cooperation of relatives, they can trace family registers, inquire at family temples to investigate lineage, and even dig up pieces of a person's life from public and private records, such as passport issuance. In this way, a concrete picture of that person's life can gradually emerge.

Kato Shinichi is not famous, but he is by no means unknown. Above all, he compiled a large book called "A Hundred Years of Japanese Americans in the United States: Development Records" published in 1961 by the Japanese newspaper "Shin-Nichibei Shimbunsha" in Los Angeles. (It seems to be a very important record that grasps the realities of the first generation of immigrants, but for some reason it is not often mentioned among researchers and experts.)

After the war, he served as deputy editor of the Chugoku Shimbun newspaper in Hiroshima, and after leaving the newspaper company, he served as the first chairman of the Hiroshima Prefectural Public Relations Committee and also as secretary-general of the Hiroshima Prefectural Headquarters of the United Nations Association of Japan. He was involved in the movement to establish a world federation and was actively involved in the peace movement. He also served as a liaison between Hiroshima residents living in the United States.

He paid tribute to the first generation of Japanese immigrants to America and worked tirelessly to organize their stories, but he also preached the importance of "global citizenship" and made great strides in the peace movement, despite losing his younger brother and sister in the atomic bombing. He also wrote about the peace movement himself, and it was featured in newspapers. In that respect, there are more clues to help us understand him than there are for ordinary people. However, trying to uncover the whole picture was not so easy. Even now, some mysteries remain.

As someone who has worked in non-fiction, it is human nature to want to investigate further when there are unknowns, especially those that no one has touched on yet. It may be a curiosity, or perhaps a professional temperament.

What kind of person was Kato Shinichi, who lived between Japan and the US, what kind of life did he lead, and what message did he want to leave behind? Some parts of the investigation are still ongoing, and some parts have been thwarted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but from next time onwards, I would like to report on what has become clear from my investigations so far, including the investigation process, in the style of a road movie, as if it were a "journey" called "Searching for Kato Shinichi."

(Titles omitted)

© 2020 Ryusuke Kawai