Los Angeles riots amid systemic racism

While efforts to rectify racial discrimination were gradually progressing, with the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the establishment of redress for the internment of Japanese Americans, under neoliberal policies, institutional racism that was deeply rooted in society continued to widen economic disparities both between and within races.

Around the same time, the immigration law was revised in 1965, opening the door to immigration, and new immigrants from Asia and Central and South America began to immigrate to America in droves. Immigrants and refugees who set out for America due to the political and economic circumstances of their home countries began living in poor areas where they were able to live, but these were often areas inhabited by black people who suffered from discrimination and poverty. Immigrants who knew nothing about the civil rights movement or the history of hardships faced by black people, and black people who knew nothing about the hardships that immigrants had endured. Due to mutual misunderstanding and the lack of resources caused by poverty, conflicts often arose between the people living in such areas.

Then in 1992, the Los Angeles riots broke out. In 1991, white police officers violently assaulted Rodney King, a black man, and a Korean store owner in a predominantly black neighborhood shot and killed a black girl, mistaking her for shoplifting. The store owner was found guilty, but instead of the prison sentence requested by the jury, he was given a light sentence of five years' probation and a $500 fine, which increased racial tensions. Then, all the police officers who assaulted Rodney King were acquitted. In response to the acquittal, black people held protest demonstrations in the streets in front of the courthouse and police station. It is not clear why the demonstrations led to the riots, but it is possible that the frustration and anger of black people who had been subjected to unjust discrimination and violence for many years erupted during the demonstrations.

On April 29, 1992, when the Los Angeles riots broke out, Mike, who worked in the South Central district, attended a community meeting about the Rodney King incident. "It was peaceful when I left, but as it began to get dark and I was leaving the meeting, a black acquaintance told me, 'Be careful. This is escalating into a racial incident,' and guided me home safely. A few days later, I went out with a black friend because there was going to be a demonstration in Koreatown, but there was no police there at all."

During the Los Angeles riots, which left 63 people dead, 2,383 injured, and caused damages totaling $1 billion, areas such as South Central and Koreatown, which are home to many minorities, including blacks, Mexicans, and Asians, were not protected by public authority and suffered greatly from the riots. For the police, these areas, which are home to many people of color, were not cities that needed to be protected. The background and results of the Los Angeles riots, which were reported as racial riots, were a distortion caused by systemic racism imposed on minorities living at the bottom of society.

However, even in the midst of this, a new movement for solidarity was born. "The Korean community suffered great damage from riots by angry black people, but in an attempt to make up for each other's ignorance and prejudice, the Korean and black communities came together and began to build new relationships. Even in the midst of any bad event, there is a possibility that something positive can start." (Mike)

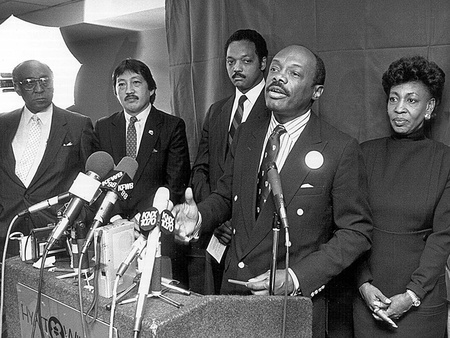

Mike first began working in the South Central area when he helped Jesse Jackson, a black civil rights activist and pastor, run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984.

"It wasn't just race that led us to support him. Jesse had a great vision for world peace, women's rights, and the environment. And he said, 'Our flag is red, white, and blue, but our country is the colors of the rainbow: red, yellow, brown, black, and white.' He thought about all races, not just black people, and in fact, when he received the second-highest number of votes in the Democratic presidential primary in 1988, the second-highest number of votes for him were Asians."

Although Jesse never won the nomination, Mike recalls that it was not a waste. Jesse's candidacy encouraged blacks and other minorities to participate in politics, and it was an opportunity for Hispanics and Asian minorities who had never thought about running for office to jump into the political world.

Are Black Lives Matter our problem?

Looking back at history, the Japanese and black communities have intersected many times, but with the widening economic gap and the fact that they live farther apart, their interactions are now extremely limited, except in isolated cases.

"After redress, the Japanese American community's attention shifted to the human rights issues of illegal immigrants. I think this was because there are fewer black people on the West Coast, where there are many Japanese Americans, and more immigrants. Also, after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the priority became speaking out against racism directed at Muslims, Middle Easterners, and South Asians," Karen says.

However, this situation has been changing over the past few months. One of the reasons for this is racism directed at Asians. The COVID-19 pandemic came at a time when an atmosphere of tolerance for discriminatory behavior had been building up across the US over the past few years. Discourse linking the virus to China was circulating, and Asians and Asian Americans, regardless of their Asian origin, have become targets of racism not experienced in decades.

"Many of us Japanese Americans have been successful in society and have lived our lives surrounded by a false sense of security, as if racism didn't exist. But it woke me up to the fact that racism could be directed at us at any time. Another reason was that there was discriminatory attitude toward black people even within our community," said Karen.

"Immigrants often come to America for a better future for themselves and their families. They aspire to a better, safer life. However, due to years of systemic racism in this country, it is primarily white people who have social power and live prosperous lives. So when they aspire to a better life, they think, 'I want to be like white people,'" (Mike).

When George Floyd was killed by a police officer in May, one of the four officers at the scene was Asian American. He was the son of Hmong immigrants who fled the Vietnam War to move to the United States, and he had developed a racist attitude toward black people in order to be successful like white people. For Japanese and Asian Americans, who have a long history of trying to be better "Americans" and be more accepted by white people, he seemed like another of "us."

Kristen says, "After years of research, I thought I understood systemic racism and my own privilege, but I realized I was just watching from a safe distance. I'm still in the process of thinking about how I can bring about real change in the society I live in. I think this is a marathon, not a sprint, and change will take a long time. But we need to start here and now."

We each have our own lives and families, the safety we want to protect, and the dreams we want to realize. There is no need to give up all of that in order to achieve fairness. Things can change if each of us continues to make small changes in our lives, such as changing the choices we make little by little, talking to friends and family, thinking and learning, and participating in politics by signing petitions, donating, voting, and demonstrating. Even if we seem powerless, even if nothing changes right now, the accumulation of small actions will change the future. That change depends on everyone who lives in and is connected to this country, regardless of nationality or race.

If we think, "This is not our problem" now, the very fact that we are able to think that is proof that we are in a safe place. And if we continue to think, "This is not our problem," then next time it may become our problem.

For "our" future

We who live in America stand not only on the shoulders of the Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans who came before us, but also on the shoulders of the history of African-Americans in America. The fairness and safety that we take for granted are built on that foundation, and we live in this country on a fragile balance.

And we who live here today are also weaving the continuation of the "history of Japanese Americans" that has lived together with other communities, including black people. How do we build the foundation for the continuation of that history and the society in which we will live in the future? That is the question we are facing now.

*This article is reprinted from The Lighthouse (Los Angeles edition, August 1, 2020; San Diego edition, August 2020; Seattle/Portland edition, August issue).

© 2020 Masako Miki / Lighthouse