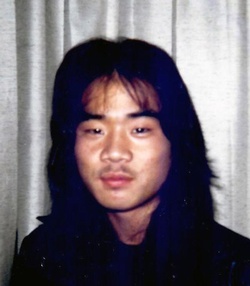

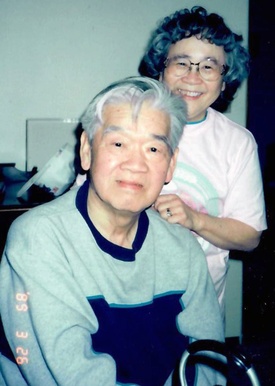

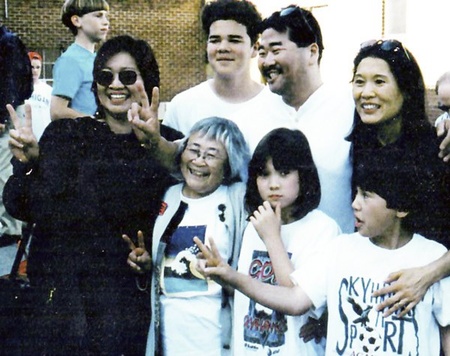

In Seattle, the Kurose family name is both legendary and synonymous with peace, activism, and community service. While the family has produced three generations of community activists, they have also experienced more than their share of personal tragedies: losing a family member during World War II, the wartime incarceration of parents Aki and “Junx” [Junelow], and losing three children—Hugo, Roland, and Guy—to cancer.

Yet, we bear witness to the first Seattle public school to be named after an Asian-American woman, Aki Kurose Middle School, an affordable housing complex named Aki Kurose Village, daughter Ruthann Kurose and her lifetime of community activism and service, and Ruthann’s daughter, Mika Kurose Rothman, continuing in the same tradition.

I have known ”activist-sister” Ruthann for decades with utmost respect, and have come to know Mika, who represents a new generation of leadership, through her community work. In this issue, we begin an engaging two-part interview series with Ruthann and Mika, while acknowledging that other family members have and continue to support and engage in important community efforts. This week’s interview is with Ruthann Kurose; the next issue will feature Mika Kurose Rothman.

* * * * *

You have always credited your parents in following in their footsteps of community activism and social change. How did they influence you growing up?

My parents taught us that activism takes many forms, and that started in our home. My mom, Aki, often hosted organizing meetings in our living room. And my dad, “Junx,” always had compassion for others and created a welcoming environment at home for any one of our friends who needed a place to stay or some food to eat.

My mother and father also formed meaningful relationships inside and outside of the Japanese-American community. Because of Seattle’s racially restrictive housing laws, we grew up in a multiracial (African-American, Asian-American, and Jewish) neighborhood, and our social networks and political alliances reflected that diversity.

My mom participated and played an active role in the local civil rights movement, which was unusual for Asian-American women. She joined the Seattle chapter of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) in their organizing efforts to integrate the Seattle Public Schools and end housing discrimination and racial segregation in Seattle neighborhoods.

Was there an aha moment or most memorable experience that stands out for you?

In 1966, at the height of the civil rights movement, local leaders of the African-American community organized a protest to demand an end to racial segregation in Seattle Public Schools. At that time, African Americans were concentrated in schools that were underfunded, staffed with less-experienced teachers, and had lower test scores and graduation rates.

A two-day boycott was organized after many failed attempts to work with the Seattle School District to implement measures to address the racial inequity. My mother volunteered with African-American leader Roberta Byrd Barr, and a coalition of African-American churches, Jewish temples, and other religious and community groups, to help organize the boycott.

For the two days, my siblings and I boycotted our school and instead attended Freedom Schools and learned about African-American history, art, and science. That was one of my earliest experiences using civil disobedience to help bring awareness to the people’s demands for equity and justice.

What experiences molded your mother in her lifelong community service and activism?

My mother’s experiences during World War II sparked her activism against racism and injustice in our society.

The day after the Pearl Harbor bombing, mom returned to school and was confused when her teacher angrily told her, “You people bombed Pearl Harbor.”

She later realized that her teacher associated my mother’s Japanese ethnicity with the Japanese government’s military aggression.

My mom graduated from high school during incarceration and was allowed to leave the camps to attend Friends University, a Quaker institution in Wichita, Kansas. The Quakers, a religious organization committed to pacifism and non-violence, denounced the incarceration of Japanese Americans and set up programs that allowed incarcerees, like my mother, to leave camp early, including accepting Japanese-American students at Quaker colleges and universities.

After the war, she joined the local Quaker-American Friends Service Committee meeting and helped with their relief efforts for Hibakusha, victims of the atom bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

She experienced and bore witness to the evils of war, in the incarceration camps and by participating in the relief efforts after the bombings. I think this left her with an undeterred commitment to peace and nonviolent conflict resolution.

What did your parents share about how their experiences in the internment camps impacted their lives?

My parents remembered how humiliating and dehumanizing it was in the camps: the dirty horse stalls, the mattresses filled with hay, how their families started to break apart under the conditions. It was incredibly traumatizing, and many Nisei were understandably reticent to talk about their camp experience or the recurring instances of racism and discrimination in their own lives. My mother and father’s takeaway was that they needed to be more outspoken about the racism and xenophobia that led to their incarceration.

What was it like growing up in an “activist family?”

Neither of my parents minced words when articulating issues of fairness and justice. And knowing what our parents encountered, we understood the urgency of actively opposing ignorance, bigotry, and violence in all forms.

My father was a Boeing machinist and would often get into political discussions with his white coworkers about civil rights. Sometimes they’d tell him to go back to where he came from.

And my dad would say, “I was born and raised here. If you don’t like what I say, you go back to where you came from.”

Often, that was enough to silence them, given that my dad was six feet tall with the physique of a black-belt judo martial artist.

My mom was a schoolteacher and when the Seattle Public Schools instituted a teacher and student desegregation program, she was moved from Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary, which had predominantly Black and Asian students, to Laurelhurst Elementary, which had mostly white students.

Some white parents confronted my mom with extremely xenophobic sentiments and a few removed their children from her class. Though some white parents continued to harbor similar ignorance, my mother overcame her feelings of anger and bitterness in the classroom. She taught her students about peace and justice, environmental science and conservation, and appreciation of global cultures. And she eventually made allies out of many of the parents who challenged her.

My mom also taught us about the human toll of war. As a science enthusiast, she was appalled that scientific research was used for the evil, widespread destruction of human life. When we were young, my mother hosted the Hibakusha, survivors of the Hiroshima atomic bombing, at our home while they received medical treatment at UW Hospital. I gave up my room while they stayed with us and remember walking into my room one day and seeing the bare back of a woman scarred with Japanese kanji letters that had been seared into her skin from her shirt the moment of the bomb flash.

The atomic bombs dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed over 170,000 people. The US deployed the bombs at a time when Japan had all but formally surrendered the war. The memory of the woman’s scarred back serves as a reminder of the needless suffering, the dehumanizing of innocent people, that accompanies war and violent conflict.

*This article was originally published in the North American Post on September 11, 2020.

© 2020 Elaine Ikoma Ko / The North American Post