3. Takahashi’s Life in Chicago

Even before he embarked for the U.S., Takeshi Takahashi had declared himself an anarchist and his comrades called him a “disciple of Kotoku.”1 It was known by his comrades in Japan that Takahashi was working hard to establish a branch of the Socialist Revolutionary Party in Chicago.2 Takahashi was a delicate, gentle, well-rounded, shy, and good-looking man, who showed no signs of the violent, stereotypical image of anarchists. It was reported that he looked as if he was always dreaming and when he was spoken to, he dropped his head a little, smiled, and answered through his nose. He read Bakunin and Kropotkin and talked about radical ideas such as the abolition of capitalism3, because he was acutely aware of the pain of being a social minority, due to his poor health. His attraction to socialism came from his conviction that for maximum happiness, powerless people should work together to defend themselves so that the system, run by a few brutal people in power, could not crush them.4

What also drew Takahashi to Chicago was that his uncle, Shichiro Yamada, and cousin, Fumio Tatsuno, were already living there. Yamada had a tea and coffee retail store, “The Far East,” at 927 North Clark Street, and Tatsuno was an engineer working for a steel mill. While staying at Yamada’s place and helping with his business, Takahashi made plans to study and experience America through the eyes of a socialist.

He read weekly socialist papers and Karl Marx in English, and wrote articles about socialists in Chicago, and sent them to Japan. For example, he reported about the Labor Day parade he participated in on September 3, 1906 as follows:

The parade was very big. They marched on Michigan Avenue and workers in shabby clothes with red ribbons marched majestically to the sound of trumpets, singing loudly, standing on carriages in excitement, shouting, with Italians and Germans talking happily hand in hand. Looking at them, I could not control my ecstasy. I visited a “nest” for laborers on West Madison and also passed by the headquarters of the Socialist Party but nothing special was happening. Workers were walking in peace with their families.5

Was the “nest” for laborers at West Madison that Takahashi visited the IWW headquarters, which was at 148 W. Madison? According to a local newspaper, about 12,000 workers participated in the parade, including members of thirty-eight labor unions in Chicago. “In point of size the parade was the smallest ever seen on Labor Day in Chicago. This was due to the fact that only about one tenth of the unions marched in the line.”6 Yet, regardless of the size of the parade, Takahashi was very excited, standing in solidarity with the workers in Chicago and breathing in their energy.

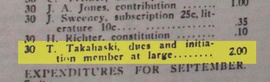

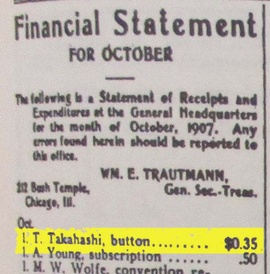

At first, Takahashi, who was inclined towards Anarcho-Syndicalism, was involved with the Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance (which was established by Daniel de Leon in 18957 but in September 1907, he joined the IWW. The record shows his payment of two dollars for a new membership8, as well as his purchase of an IWW button, for 35 cents, to support the organization.9 “I am still an anarchist, but not for Steinell or Bakunin or Kropotkin or Emma Goldman. I am for the IWW. I will fight against all privileged classes. Direct Action!” Takahashi excitedly told his friend, Maedako.10

There was another Japanese socialist in Chicago who had a close relationship with Denjiro Kotoku. This was Kiichi Kaneko, who had joined the Socialist Party of America in New York in 1903, and moved from New York to Chicago with his wife, Josephine, in October 1906. Kotoku introduced Takahashi to Kaneko right after the latter’s arrival in Chicago. “There is a lad by the name of Takeshi Takahashi in your city… He is a hopeful little fellow. I told him to go to your place occasionally. Please give him good lessons.”11

After that point, Takahashi and Kaneko must have met now and then as Japanese socialist comrades. Although their situations were quite different, Takahashi being single and Kaneko married to an intelligent American woman, their Chicago lives were united in the desperate struggle for hope through their idealized dreams of universal humanity in the harsh, racist climate of America.

Unfortunately, Takahashi’s daily life was miserable, as his uncle Yamada detested socialists. Pictures of Karl Marx on Takahashi’s wall were frequently torn down, and the weekly socialist papers to which Takahashi subscribed disappeared from his attic room.12 Yamada also abused Takahashi by overworking him as a tea and coffee carriage driver and deliverer. He had to work every day from early morning to late evening, with a short lunch break, and got paid very little. Takahashi complained, “Delivery men should be members of AFL. I got asked several times if I were a member of union or not. If uncle uses members of the union, he has to pay surprisingly high pay. At least 50 cents per hour. If you work eight hours a day, you get paid 4 dollars a day, and they charge overtime too. They can get paid at least $30 per week at uncle’s store. I get only $10 per week and no pay for overtime.”13

As Takahashi was also responsible for supporting his father and regularly sent some money to Japan14, he was totally exhausted from the hardship of daily life. When Hiroichiro Maedako, Takahashi’s friend from Japan, came to Chicago in 1907 and joined him at Yamada’s store, Maedako realized that Takahashi was far from happy, although he had been extremely excited about his trip to the U.S.15 Despite his financial difficulties and miserable life, Takahashi still had hopes for making a contribution for the betterment of the society and the world, and imagined himself delivering agitating speeches on the streets.16

4. Under the Surveillance of the Japanese Government

The Japanese government, on the other hand, had been seriously investigating anti-government Japanese living in the U.S. since the Russo-Japanese War in 1904.17 Kotoku’s activities in San Francisco were under government surveillance” and a “‘top secret’ history of Japanese radicals” in the U.S. between 1906 and 1911 was compiled by Japanese government ‘spies.’18 It was reported to the Japanese government that Chicago was a city where “many anarchists from China, Chosen [Korea], and Europe gathered and anarchist magazines were also vigorously published. There are many Japanese students who are supported financially by those anarchists. There are even two Japanese women who are anarchists.”19 In a 1911 secret–report for the Japanese government, “Takeshi Takahashi” was listed as a member of the Social Revolutionary Party, and the address listed was 927 North Clark St., the address of Yamada’s tea and coffee business.20

Kaneko had been “warned that a group of spies have been detailed to this country by the Japanese government to watch the ‘little brown men’ here, and to deport anyone who could be dubbed as an ‘anarchists.’21 Kaneko was under surveillance as one of “seven dangerous Japanese,”22 most likely because he and his wife, Josephine, contributed to The Revolution, the publication of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, in early 1907. Among the list of publications that were prohibited from being imported and distributed in Japan were The Revolution, Appeal to Reason, (a weekly socialist newspaper published in Girard, Kansas, where Josephine Conger Kaneko had worked as reporter before her marriage,) The Progressive Woman, (which Josephine published in Chicago,) The International Socialist Review, and Mother Earth, which was published in New York.23

Although poverty and the harsh racist reality of America affected and gradually changed Takahashi and his ideas, he was among the very first Japanese to make personal contact with Emma Goldman, famed anarchist and publisher of American anarchist journal, Mother Earth, which was based in New York. Emma Goldman spoke highly of Takahashi, calling him an “energetic comrade.”24

Notes:

1. Maedako, Ore no Sanjyu-Roku Nen.

2. Hikari, July 20, 1906 .

3. Maedako, “Takechan,”Nichibei Shuho, December 29, 1917.

4. Akai Basha, page 30.

5. Hikari, November 5, 1906.

6. Chicago Daily Tribune, September 4, 1906.

7. Maedako’s letter to Tokutomi, November 14, 1910.

8. Industrial Union Bulletin, October 26, 1907.

9. Industrial Union Bulletin, November 16, 1907.

10. Nakata, Sachiko, Maedako Hiroichiro ni Okeru “Amerika,” page 158.

11. Kotoku’s letter from to Kaneko, Nov 17, 1906, The Progressive Woman, May 1909.

12. Akai Basha, page 32.

13. Maedako, Ningen (Tairiku-hen), page 390.

14. Shakai-shugi-sha Museifu-shugi-sha Jinbutsu Kenkyu Shiryo 1.

15. Maedako, Hiroichiro, Seishun no Jigazo, page 55.

16. Ibid, page 76.

17. Matsuo, Shoichi, “Kaidai”, Beikoku ni Okeru Nihonjin Shakishugi-sha Museifushugi-sha Enkaku, page 12.

18. Notehelfer, F.G., Kotoku Shusui: Portrait of a Japanese Radical, page 132.

19. Tetsuo Son’s letter to Sakuei Takahashi, May 7, 1910.

20. Shakai-shugi-sha Museifu-shugi-sha Jinbutsu Kenkyu Shiryo 1.

21. The Progressive Woman, May 1911.

22.The International Socialist Review, March 1908.

23. Beikoku ni Okeru Nihonjin Shakishugi-sha Museifushugi-sha Enkaku, page 402.

24. Mother Earth, July 1910.

© 2020 Takako Day