5. Emma Goldman, Kotoku and Takahashi

In 1907, Mother Earth introduced Kotoku’s new publication, Heimin Shimbun, which he started in Japan, right after he returned from the U.S. in 1906. The announcement they ran read as follows: “A daily revolutionary socialist paper, Heimin Shimbun, is out at Tokyo. If some Japanese American comrade will kindly offer to give us an idea of its contents we shall be glad to send him copies.”1 It may have been Takahashi who answered the call, because in the fall of 1907, Takahashi went to New York to meet Goldman. According Maedako, Takashi reported: “I went first to the Local to join the Drivers Union in New York. But they did not accept me because I am Asian. That is the policy of Gompers of AFL. So I worked as domestic for a while and went to meet Emma Goldman and she welcomed me.”2

Emma Goldman criticized the “yellow peril” scare as follows: “As long as the Capitalists of Europe and America could, with the aid of their respective governments, carry their “civilization” into Asia and force the latter’s truly cultured people to buy their shoddy wares, there existed no yellow peril. Only when the ‘heathens’ began to practically apply the lessons taught them by their white ‘benefactors,’ when they, too, began to propagate civilization-lo! Suddenly we received the yellow peril!”3 Takahashi must have been deeply moved by Goldman’s words and, in New York, donated one dollar to the weekly fund for Mother Earth.4

But Takahashi only lived in New York City for a few months. In February 1908 he was on his way back to Chicago and again donated 50 cents to the Mother Earth Sustaining Fund from Greenwich, Connecticut.5 On March 9, 1908, back in Chicago, he paid 50 cents as a “dues member at large” of IWW.6 Takahashi received letters from his comrades in Japan and the San Francisco Bay Area explaining how socialists were being persecuted in Japan, that expressed their anger and sorrow.7 Takahashi learned from them that the freedom of speech, including anti-government publications, was severely restricted in Japan.

Lamenting the oppressive atmosphere, several comrades of socialists and anarchists from Japan and other areas in the U.S. visited Takahashi, sometimes bringing letters of introduction from other comrades in Japan.8 K. Tetsuka must have been one of them. According to Maedako, a “comrade” called “Tetsuka” helped with Yamada’s tea and coffee business for a while.9 K. Tetsuka also paid one dollar to be a “dues member at large” of IWW and bought an IWW handbook for one dollar on March 13, 1908.10 Might this “K. Tetsuka” have been Koyata Tetsuka, a socialist and frequent speaker at meetings, known to be living in Berkeley, California?11 It is not known how long Tetsuka stayed in the Midwest, but he died in San Francisco in 1915, at the young age of thirty five. Other Japanese anarchists who probably visited Takahashi in Chicago included Tsunekichi Tomita and Satoru Saijo.12

Tomita, a Christian, arrived in San Francisco from Japan with an American missionary in 1903. There, he joined the Socialist Party of America. After coming to Chicago, it was reported that he was working at a newspaper company.13 He moved back to San Francisco in 1918,14 and lived there until he passed away at the age of 52 in 1935. Saijo, a Christian as well, moved from Berkeley to Chicago in 1907 and found work there.15 It was reported to the Japanese government that he also lived in Dubuque, Iowa, and ran a “Jap Bazaar” [flea market] in Cedar Rapids during his U.S. residency.16 By 1919, Saijo had abandoned his radical ideology and become a minister of the Japanese Congregational Church in Southern California.17 He married in 1921, had three children in California, and died in Los Angeles in 1956. An interesting clue to his activist past emerged when he named his first son, Gompers, after labor activist Samuel Gompers.18

In the fall of 1908, once again, Takahashi donated one dollar to the Mother Earth Sustaining Fund.19 It was obvious that Emma Goldman had changed her attitudes about Japan and Japanese, as she now had direct contacts with comrades such as Takahashi and Kotoku. Previously, she had not been so kind. The first issue of Mother Earth, on March 6, 1906, mentioned Japan sarcastically: “Japan- A new civilization… They were mocking themselves and did not know how… She can take her place in the ranks of other civilized countries. Rejoice! … Nearly a million people, it is laconically reported, are in danger of dying of starvation. Surely no one will possibly doubt now that Japan is a civilized country.” Kotoku reported back to Japan about this first issue of Mother Earth from San Francisco.20 In the May 1907 issue, Mother Earth introduced proclamations of the Socialist Revolutionary Party as “a very hopeful sign of the times” and “a remarkable document, which indicates that the American workingmen have a great deal to learn from their ‘heathen’ brothers.”21 Following this, direct communication between Kotoku and Goldman was established, and Kotoku and his comrade, Kuranosuke Oishi, subscribed to Mother Earth from 1907, for nearly one and half years.22

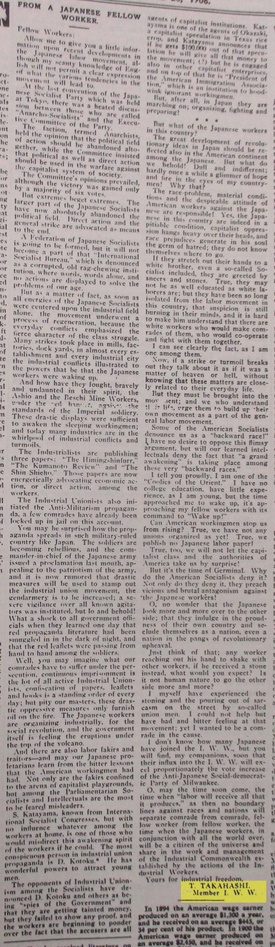

As if encouraged by the warm relationship between Goldman and Kotoku, Takahashi wrote a long statement titled “From Japanese Fellow Worker,” which was published in two center columns on the front page of the Industrial Union Bulletin in 1908.23 First, he explained recent developments in the Japanese labor movement and praised Kotoku as a hero of the movement. Then he shifted his tone to call Japanese immigrants and American workers to action. He exclaimed in the article; “Dull and indifferent, hardly once in? a while a glimmer of hope and fire in the eyes of my country men. Why that? The race problem, material conditions and the despicable attitude of American workers against the Japanese are responsible!” “If they stretch out their hands to a white brother, even a so called Socialist included, they are greeted by sneers and stones … It is hard to make him understand that there are white workers who would make comrades of them, who would co-operate and fight with them together.”

Calling himself “one of the ‘Coolies of the Orient,’” he continued “I myself have experienced the stoning and pouring out of sarcasm on the street by so called union men. I could not help but have bad and bitter feeling at that moment, yet I wanted to be a comrade in the cause.”

Takahashi had hoped to publish his own newspaper with financial support from the political groups he frequented.24 He declared in the above mentioned article that “the time approached me to wake up my fellow Japanese immigrant workers,” and finally realized his dream in the spring of 1909 by launching The Proletarian, a one sheet, bilingual newspaper for the “emancipation of the Japanese workers in America.”25 The Proletarian was printed at 935 Wells Street and a subscription was 50 cents a year.26

It is almost impossible now to find an original copy, but we can get a glimpse of what it looked like, since Mother Earth reprinted part of The Proletarian in July 1910 as follows:

Recent conditions prevailing among Japanese workers on the western coast are deplorable. A vast throng flocked in front of an employment agency seeking a job even in mid-summer. The active anti-Japanese movement for the last three years has been effective enough to drive them out of certain districts and concerns. The movement employs a cowardly and sneaking method, even using means of violence. Japanese are attacked in day time openly on the streets of the western metropolis and no one interferes. At the same time, what are the capitalists of both countries realizing to-day? They are greeting each other with best wishes over the pacific billows, and do not hesitate to compromise whenever their interests demand it, though, they are engaged in hot commercial fighting in the markets of China. How cordially was Prince Kuny, who represented aristocratic Japan, received in the White House! How did Baron Shibusawa and his party, which represented plutocratic Japan, meet with the hospitality of American capitalists, as they travelled through every city while you, You workingmen, greet Japanese workers by the throwing of bricks and sneering. However, let these be the affair of the past. The time now reaches us that such a trifle difference should vanish altogether, and we should and must unite upon a common interest against our real enemy, the capitalist class. Let us unite! Not only in words, for unless our unity develops into action, the emancipation of wages slaves cannot be accomplished. Salvation lies in the unity of workmen regardless of race or color.27

The publication of The Proletarian was, of course, reported to the Japanese government. According to a secret report, the principles of The Proletarian were “to organize Japanese workers in the U.S., to make them resist capitalists and the government, and to destroy national unity.” Takahashi was reported to have “cursed the Japanese government for success in preventing the development of socialism, to be mad at the severity of arrests of socialists, and to have published personal attack on diplomats in Chicago.” Furthermore, the Japanese government suspected that The Proletarian was supported by funding from an American socialist newspaper in New York.28 It is unknown whether Takahashi actually received any funding from socialist groups or Emma Goldman, but The Proletarian was short lived due to lack of funds.

Notes:

1. Mother Earth, May 1907.

2. Seishun no Jigazo, page 92.

3. Mother Earth, May 1907.

4. Mother Earth, Jan 1908.

5. Mother Earth, April 1908.

6. Industrial Union Bulletin, April 18, 1908.

7. Seishu no Jigazo, page 109.

8. Maedako, Hiroichiro, Dai-Bofu-U Jidai, page 111.

9. Seishu no Jigazo, page 84.

10. Industrial Union Bulletin,April 18, 1908.

11. Tetsuo Son letter to Sakuei Takahashi dated May 7, 1910.

12. Shakai-shugi-sha Museifu-shugi-sha Jinbutsu Kenkyu Shiryo 1.

13. Shakai-shugi-sha Museifu-shugi-sha Jinbutsu Kenkyu Shiryo 1.

14. WWI registration.

15. Shakai-shugi-sha Museifu-shugi-sha Jinbutsu Kenkyu Shiryo 1

16. Beikoku ni Okeru Nihonjin Shakishugi-sha Museifushugi-sha Enkaku, page 112.

17. WWI registration.

18. 1940 census.

19. Mother Earth, Oct 1908.

20. Hikari, April 20, 1906.

21. Mother Earth, May 1907.

22. Yamaizumi, Susumu, “Dare ga ‘Red Emma’ wo Mita Ka,” Shoki Shakai Shugi Kenkyu No 4, December 28, 1990.

23. Industrial Union Bulletin June 20 1908.

24. Dai-Bofu-U Jidai, page 141.

25. Mother Earth, July 1910.

26. Mother Earth, July 1910.

27. Ibid.

28. Shakai-shugi-sha Museifu-shugi-sha Jinbutsu Kenkyu Shiryo 1.

© 2020 Takako Day