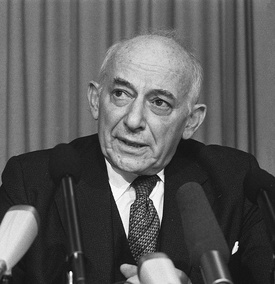

In the annals of civil rights, a special place should be reserved for Eugene Rostow. In 1945, even as Japanese Americans remained confined in camps by official order, Rostow, then a young law professor at Yale University, published a pair of articles that criticized their wartime treatment. In his first article, “The Japanese-American Cases - A Disaster,” published in the Yale Law Journal in mid-1945, Rostow presented a powerfully-reasoned critique of removal and incarceration as America’s “worst wartime mistake,” and refuted the official justifications offered. He followed this with an article in the popular magazine Harper’s in September 1945. Designed for a larger public, it repeated the same critiques in more summary form.

In addition to denouncing mass confinement in his twin articles, Rostow endorsed the concept of reparations for the victims of the policy. While Carey McWilliams and a small number of other writers had denounced West Coast racism, Rostow’s articles were among the first to directly challenge the legitimacy of Executive Order 9066 and the Supreme Court decisions upholding the government’s actions under it.

Eugene Victor Rostow was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1913. His parents, Russian-Jewish immigrants, named him in honor of Socialist Party leader Eugene Victor Debs. After studying at Yale University and Cambridge University, Rostow graduated from Yale Law School in 1937. So impressive were his studies that he was asked to return after graduation and teach law. In the wake of US entry into World War II, Rostow, who was then still in his late twenties, obtained a leave of absence from Yale and moved to Washington, where he served in the Lend-Lease administration and later the State Department.

In mid-1944, following an outbreak of back pain, Rostow left Washington and resumed teaching at Yale, where he was appointed full professor of law. On September 23, 1944, he wrote Undersecretary of the Interior Abe Fortas that he had decided to “celebrate” his return to academia by studying the “Japanese exclusion cases” (by which he meant primarily the case of Korematsu v. United States, which was about to be argued before the Supreme Court). Rostow asked Fortas whether he could do him the favor of having a member of his staff provide information that might “safely be made available” in four areas: restrictions on activities of Japanese Americans in Hawaii; any actual incidents of sabotage among those in Hawaii or the mainland; general information on the operation of the camps; and the official justification for legal restrictions. “It is not persecution that leads me to write articles against the positions in which you officially find yourself!” He assured Fortas. “I just don’t like these Japanese cases, which lead to the conception of second-class citizenship, and strengthen the hand of our worst kind of reaction.”1

On one level, it was an audacious request. Since the Department of the Interior oversaw the War Relocation Authority, Rostow was in effect requesting that the administrator responsible for administering the camps act as a “mole” and feed him some private material to attack the government’s policy. Rostow did not even bother to hide his own position—while he insisted that he did not consider official treatment of Japanese Americans to be “persecution,” he clearly regarded it as discriminatory.

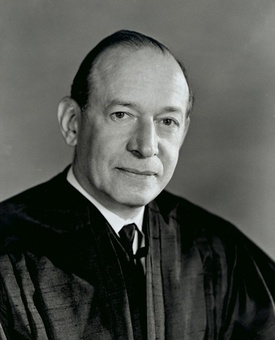

On a deeper level, however, Rostow had clearly come to the right man for help. First, he was connected to Fortas by significant bonds of background and experience. Born just three years apart, both men were descended from Russian Jews, had studied and taught at Yale Law School in a period when Jews were a rarity there—in fact, Rostow had taken a class from Fortas—and then served in government agencies during World War II. While it is uncertain how personally close they were, Rostow addressed Fortas as “Abe” and signed himself “Gene.”

Furthermore, since they had common contacts in Washington, Rostow would surely have had reason to know that Fortas (like his boss, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes) was supportive of Japanese Americans and critical of the Army’s mass removal policy. After the Interior Department assumed authority over the War Relocation Authority in late February 1944, Fortas wrote WRA Director Dillon Myer a letter in which he stated that the entire removal and exclusion had been a “terrific mistake,” but that he recognized that there was nothing he could do about it. Rather, his task was “to ameliorate the evils which resulted from it.”2 Fortas spent significant efforts during Spring 1944 working with the War and Justice Departments to build support for opening the camps and permitting the inmates to return to the West Coast, but in spite of their united position that there was no national security reason to keep concededly loyal Japanese Americans from returning to the West Coast, President Franklin Roosevelt refused to lift exclusion and open up the camps.

In the event, Fortas immediately agreed to aid Rostow. Just three days later, he wrote that he was collecting material to send Rostow in response to his request. He suggested that for the question of Japanese Americans in Hawaii, Rostow contact John P. Frank, Fortas’s former assistant at the Interior Department who had moved to the Department of Justice, as Frank had collected a significant amount of material on the case of Hawaii. Fortas hastened to reassure Rostow that he could write whatever criticism he wished about the government’s policy:

“You need not have any compunctions on my account with respect to the Japanese exclusion situation. My own position is open and notorious, as is the position of the War Relocation Authority and Secretary Ickes. We have no jurisdiction to eliminate the West Coast ban. Our jurisdiction is solely to run decent hotels and to relocate the Japanese Americans as speedily and effectively as possible. We have, however, done all that we could to put an end to a situation which has no basis in the necessities of the war and which is without legal foundation.”3

Fortified by Fortas’s response, Rostow proceeded to contact Frank. He explained that he was engaged in “kicking, gouging, and otherwise assaulting the Supreme Court for its Japanese follies,” and asked Frank for materials that would help him.4 Frank responded that he was more engaged in studying the larger question of Martial Law in Hawaii, and suggested that Rostow travel to Washington for the upcoming oral arguments in Korematsu, then start writing his article so that it would be ready by the time that the Court issued its decision.5

Despite Frank’s advice, Rostow did not get to the writing immediately. In a March 26, 1945 letter to his friend David Riesman, whom he congratulated for producing an essay on civil liberties, he expressed his frustration: “I have been boiling about the Japanese cases ever since I came back here, and [am] intending to celebrate my return to the law by tearing the court to pieces, in the classic law review manner.”6 By May 1945, he had a draft of his law review article ready, which he submitted to Fortas. Fortas in turn sent the draft on to WRA Director Dillon Myer for his comments.

Myer replied on June 28, 1945, offering correction of factual mistakes and rebuttal of what he considered errors of perspective. Myer argued that Rostow failed to understand the circumstances that led to the camps, in protecting Japanese Americans from the threat of mob violence on the West Coast. Myer argued that confinement was justified to safeguard the community, because he viewed police protection against vigilantism to have been “spotty at best.”7 Furthermore, despite his private frustrations with continued exclusion, he accused Rostow of failing to recognize the advantages of the controlled resettlement program in allowing the WRA to “develop community acceptance throughout the country.”8 Although Myer had defended Japanese American loyalty during his tenure at WRA, and he would later express public skepticism about whether mass removal was justified, his response to Fortas revealed primarily his bureaucratic temper and desire to shield the WRA from criticism.

Paradoxically, Myer’s long critique of Rostow so exposed the weak nature of the government’s case for confinement that Fortas distanced himself from it in his own response to Rostow, dated the same day as Myer’s. “With your criticism of the Supreme Court’s decision in the Korematsu case I am in accord.” Indeed, Fortas confided in Rostow that all the government officials who had been involved in Korematsu had correctly predicted that the Supreme Court would sustain mass removal. Conversely, Fortas noted that the government officials involved were aware that they were unlikely to prevail in the case of Ex Parte Endo, Mitsuye Endo’s habeas corpus challenge to her confinement. Fortas affirmed that as a result, he had been forced to fight to ensure that Endo’s case was heard by the court.

Eugene Rostow’s article, which appeared in the summer 1945 issue of Yale Law Journal, pointed up Abe Fortas’s influence. Not only did he make use of the information that Fortas had sent him, but the final text included a citation from Fortas’s June 28 letter. Soon after Rostow’s articles appeared, Fortas unleashed his own blast. On December 9, 1945, Fortas published a “communication’ in the Washington Post praising its editors for their defense of fair treatment for Japanese Americans, and stating flatly that racial prejudice was a leading cause of attacks on their loyalty. It was an extremely forthright statement, especially coming at a moment when Fortas still worked for the government.

Fortas and Rostow would remain in intermittent contact in later years. In 1965, when Fortas was appointed to the US Supreme Court, Rostow, by then Dean of Yale Law School, celebrated by publishing a brief reminiscence of his old teacher. Tragically, the two men would also be linked in the years that followed, as the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War escalated. Both men were called on as counselors by President Lyndon Johnson, and both distinguished themselves as “hawks” in regard to the military conflict (as did Rostow’s brother, National Security Advisor Walter W. Rostow).

After resigning from the Supreme Court under a cloud in 1969, Fortas returned to private practice. In late 1981, he was called to testify before the U.S. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. While Fortas expressed compassion for the past government officials acting in the shadow of Pearl Harbor, he was clear that his position had not changed: “I still believe that the mass evacuation of those of Japanese ancestry and their prolonged detention was a tragic error, and I cannot escape the conclusion that racial prejudice was a basic ingredient.” Fortas told the Commission members of the emotional shock he had felt when touring one of the camps and visiting a schoolroom where he heard students sing “America the Beautiful.” Fortas’s CWRIC appearance was his last significant public act. He died less than six months later, in April 1982.

*Thank you to Sarah Ludington, Brian Niiya, and James Sun for their assistance with research for this article.

Notes:

1. Letter from Eugene Rostow to Abe Fortas. September 23, 1944. Eugene Rostow Papers, Yale University (henceforth Rostow papers).

2. Letter from Abe Fortas to Dillon S. Myer. March 31, 1944. Cited in Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans , Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2001, p. 208

3. Letter from Abe Fortas to Eugene Rostow. September 26, 1944. Rostow papers

4. Letter from Eugene Rostow to John P. Frank. October 6, 1944. Rostow Papers.

5. Letter from John P. Frank to Eugene Rostow. October 7, 1944. Rostow Papers.

6. Letter from Eugene Rostow to David Riesman. March 26, 1945. Rostow Papers.

7. Letter from Dillon S. Myer to Abe Fortas, June 28, 1945. CWRIC Papers, National Archives.

9. Ibid.

© 2019 Greg Robinson, Jonathan van Harmelen