This story is about my Auntie Yochi based on family knowledge, my memories of her, several writings about her in letters and passages in books.

Yoshiko (Yochi) Ukita was born in Los Angeles on December 8, 1918. She was the daughter of Frank Masashi and Tsuya Ukita. She was their only daughter and the second of four children. She passed away in Chicago on September 8, 1951 when she was only 32-years old. In her short lifetime, she had a deep desire and commitment to help others: giving her very best to benefit those in need of her assistance. Besides my own, there are contributions from others in this writing expressing their appreciation in regards to her helpfulness and the influence she had on them. She unforgettably touched my life, as well as, all her family members, friends, and acquaintances whom she cared for and helped.

Auntie Yochi, like her older brother, my Dad, attended 28th Street Elementary School, John Adams Junior High School and Polytechnic High School in Los Angeles. After high school graduation in 1937, she attended UCLA for two years. After leaving the Manzanar Internment Camp in late 1943, she worked and attended colleges in Kansas City, Chicago, and eventually Berkeley. In 1947, she received her Bachelor of Arts degree in social welfare from the University of California, Berkeley. She began her graduate studies at the University in the Social Sciences Department.

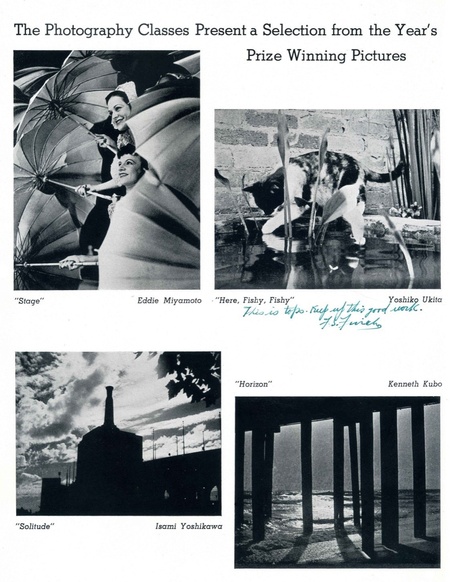

Yochi was often called “Yo” and “Yo-Yo” in elementary school, junior high school, and high school. In her high school yearbooks, her classmates and teachers addressed their written commentsto “Yo,” “Yoshiko,” “Yo-Yo.” She participated in many high school activities. These included being on the journalism staff, member of GAA, and photographer for the school newspaper and yearbook. There are numerous comments in her yearbooks recognizing her talent for journalism and for photography. At some point, likely during her high school years, she was given an expensive 35mm Leica range-finder camera as a present from her friend, Fumi Okamoto. Fumi was a long-time childhood friend and she considered Fumi like an older sister. As this was the time of the Great Depression, Fumi had to save a lot of hard-earned money to buy this special camera. Auntie Yochi took many terrific photos with the Leica including action photos of Dad going over hurdles as he trained for a track meet, as well as a prize-winning photo in high school.This prize-winning photo, titled “Here, Fishy, Fishy,” was selected as one of four prize winning photographs for the high school yearbook. Mr. Fred Finch, who was responsible for photos for the yearbook, wrote under her prize winning photo, “This is tops. Keep up the good work.”

In her yearbook, there are many comments written by fellow students gratefully thanking her for the assistance she provided in helping them understand various class subject matters, and there are comments written by her instructors recognizing her assistance to them. Miss Frances Hov, the journalism teacher, wrote in Yochi’s 1937 yearbook the following:

I can’t even imagine how I’d have lived without you (up to 3 weeks ago-but won’t go into that) this year. Where do you suppose I can get your twin.

Seriously I love you Yo-yo - shall remember you always and be wishing you happiness.

Many, many thanks. (signed) Frances Hov

After graduating from Polytechnic High School, Yochi attended UCLA from September 1938 to June 1940. From copies of records I obtained from the National Archives, I learned that she worked as a salesclerk at a fruit stand in Montebello from April 1941 to early March of 1942; then the events of the World War II created drastic changes for herand most everyone in this country and throughout the world.

The entire Ukita family was incarcerated at Manzanar Relocation Center in April of 1942, soon after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The Ukita family lived in Block 4, Barrack 11, Units 1 and 2. In Manzanar Yochi was associated with the Community Welfare Office under the direction of Margaret Matthew D’Ille. She was involved in assisting destitute families in two blocks of the Manzanar Relocation Center. In a letter of reference (dated 11MAR43) written by Margaret D’Ille, obtained from the National Archives, it states:

… [Yochi] having in her charge the destitute families in two blocks of this center. She has done very good work, especially with the larger family cases. She is not a trained case worker, but had two years at U.C.L.A. and took as much work as she could in the social work field …

Margaret Matthew D’Ille’s amazing life story of her dedication in providing care and concern for others is presented in a recent book entitled In Good Conscience: Supporting Japanese Americans During The Internment. This book states that she graduated from the University of California at Berkeley; and pursued a lifetime of social and Christian service, including ten years in Japan between 1908 and 1918 with the International YWCA. As presented in this book, John Anson Ford, a Los Angeles County Supervisor, said that she radiated “love, kindness, sympathy, helpfulness and faith.” Also, in this book, it states that at her funeral service, Miya Kikuchi (a social worker at Manzanar) said, “She has not left us, because the kindly, the gay, the wonderful things she did live on in us.” Margaret Matthew D’Ille’s dedication to help and be of support to others, such as those incarcerated in Manzanar, may well have further influenced Yochi’s own life’s dedication in helping others in need of support, advice, and assistance.

While in Manzanar Yochi became close friends with Karl and Elaine Yoneda, and their young son Tommy. Karl Yoneda and Elaine Black Yoneda deeply influenced Yochi’s thoughts about labor rights, labor unions, and minority rights. Both Karl and Elaine Yoneda were devoted in fighting for the welfare and rights of laborers and the establishment of labor unions. Karl Yoneda was a Japanese American (JA) who received his education in Japan. Such a person is known as a “Kibei” by other Japanese Americans. Elaine Black Yoneda was not of Japanese ancestry but of Russian-Jewish ancestry. There is a book, The Red Angel: The Story of Elaine Black Yoneda, that tells about her life and her and Karl’s lifetime efforts to provide better working conditions, social justice, and equality for minority people.

The story of Karl and Elaine’s pursuits of change and justice for the rights and betterment of the working people and minorities is also presented in the book “Ganbatte: Sixty–Year Struggle of a Kibei Worker.” Karl and Elaine were activists not just speaking words but getting out there to provide their help in ways directly beneficial to blue-collar people and minorities. Some people would degradingly call Karl and Elaine Socialists and Communists, and in doing so never understood that what they actively thought and accomplished helped make this country a better place; protecting workers from over-exploitation and minorities from discriminatory actions and practices.

Karl and Elaine were staunch supporters of this county’s efforts to fight against the fascist Axis Powers. In 1942, Karl was one of the very first Japanese Americans in Manzanar to volunteer for military service.He was accepted into the U.S. Army Military Intelligence. Karl and Elaine’s commitment in providing vocal military support for this country’s efforts against the Axis Powers were not well taken by certain other internees in Manzanar. There was a group of internees known as the “Black Dragons.” This group made efforts to intimidate and threaten harm to others who supported JA involvement in the fight against the Axis Powers. Some members of the Black Dragon group actually physically harmed other internees who supported this country’s efforts against the Axis Powers. When Karl left Manzanar for Army training in 1942, the Black Dragon group threatened bodily harm to Elaine and Tommy. In the book Only What We Could Carry: The Japanese American Internment Experience by Lawson Fusao Inada, there is a compilation of many writings about personal thoughts and experiences of the internment. Elaine Black Yoneda provides her writing about the Yoneda family and their Manzanar experiences. Concerning threats to her and Tommy, she writes:

Satoru Kamikawa, Issei UC graduate and a Manzanar Free press Japanese Section reporter, came running over [on 6DEC42]. He repeated what Chester told me, adding “Go back to your apartment, lock yourself in, and don’t even go out for meals.”

With Tommy in tow, I ran to the Camp Police Station requesting protection at our apartment but none was offered. We proceeded at a run to our apartment, barricading the door with the inside bolt and the table.

Yo Ukita came over towards dusk and said she would try to get us some food and spend the night, although things were tense out there. An hour later she returned but was unable to stay because her father had forbidden her to do so due to threats to him and the rest of their family.

* * * * *

At daybreak [7DEC42] we were all taken by Army trucks to the MP encampment and crowded into the small, two–room dispensary building for meals and “rest.” Late that afternoon our good San Francisco friends, Tom Yamazaki, Issei UC graduate journalist, his Nisei wife, Ruth (both antifascists), and two young daughters arrived at the MP quarters. Yo Ukita and six other members of her family were also brought in. She indicated it would be all right for her to remain with us. But her father insisted they all go back to Block 4 and the Army took them back. (It would be five years before we were to meet again.) …

Yochi maintained a close bond with the Yoneda family for the remainder of her life. After the war, she would visit them in Petaluma where they had a chicken and egg ranch. During that time she was attending the University of California, Berkeley.

Yochi was an early civil rights activist involved in civil rights affairs while attending the University of California, Berkeley. She was secretary of the local NAACP chapter, and per the records of the Social Sciences Department at the University, she volunteered to do social work at the Trinity Community Center in Oakland, California. She received her BA degree in 1947 as mentioned above, and continued her education in efforts to obtain a MA in social welfare. She did not complete the program to receive a MA at the University. She moved to Chicago in about 1949.

Auntie Yochi had strong feelings about the plight of the blue-collar working people of this country. Her understanding about the plight of minorities, such as the discriminations against Black Americans and the disparities they lived under, resulted in her speaking out and being an activist doing whatever she could to help rectify the poor conditions that Black Americans faced in this country. In Chicago she worked as a social worker providing assistance to Black American families.

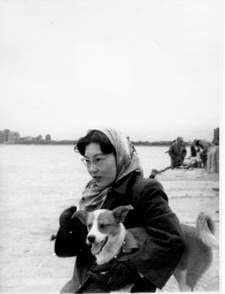

I remember that Yochi obtained a pet dog she named “Sanjo.” She cherished Sanjo, and there are two wonderful winter-time photos taken on the Chicago lake front with Sanjo being held in the arms of Yochi. One photo seems to show her contemplating something and maybe wondering what could be in or beyond the waters of Lake Michigan.

Yochi was diagnosed with advanced breast cancer. She underwent a mastectomy and cancer treatment which did not cure her of the cancer. She passed away on September 8, 1951. Grandma Ukita tried her utmost to help cure Auntie Yochi of the cancer by utilizing Japanese developed Nishi Shiki health treatments at our home. She gave Yochi hot and cold bathing treatments. Grandma made a special pulverized blend of vegetables into juices hoping to cure Yochi. Grandma worked with untiring diligence, never complaining about why such a sickness had come upon her daughter.

When we visited Japan in October 2011, we were told by Grandma’s youngest niece, Sachiko Kotake, that Grandma told her that the day Yochi passed away a strange thing happened. The next-door neighbor told Grandma that Yochi’s pet dog, Sanjo, cried and howled at the time that Auntie Yochi passed away in the Chicago hospital. Not long after she passed away, Sanjo her beloved pet dog was never to be found.

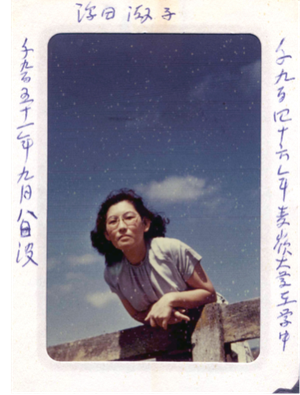

Grandma kept a wonderful color photo in her album of Auntie Yochi leaning on a wooden fence.

At the time of her funeral service, her good friend Betty Moore sent a telegram to the family. Betty Moore was a wonderful friend to Yochi. While I was reading one of Dad’s many diaries during the evening of 3DEC12, I found he had copied the words of the telegram. The following is what Betty wrote in her September 11, 1951 telegram:

Yo was one of the best friends I’ve ever had. Her courage in the face of difficulties and sufferings was admirable. She believed in the dignity and worth of all men and dedicated her life so that this might be a reality in our society. Yo’s mind was hungry for the truth and she searched faithfully for it and lived committed by what she believed. Hers was a spirit that will never die but live in the hearts and lives of all whom she touched. She was genuine loving friend. Those of us who loved her must continue the work and live for the things she held most dear. She lived a full rich and happy life. May she rest in peace and her family be comforted in their sorrow and loneliness.

Betty Moore’s telegram is so emotionally and beautifully written: capturing Yochi’s inner being and dedicated life endeavors. I can’t remember ever reading anything more touching and meaningful about another’s thoughts about a friend or family member. Her message is truly a heartfelt tribute to Yochi. What was pertinent for me to understand and deeply appreciate from Betty’s writing was Yochi believed in the dignity and worth of all, searched faithfully for it and lived committed to what she believed. It is so clear why Dad had maintained Betty’s writing in his diary for he knew that these words fully captured the life and spirit of his beloved sister.

For me, there is no need to contemplate the meaning of the wonderful photo of her above and the photo of her with Sanjo. For these photos, thoughts by others about her and my remembrances, created in me a strong commitment to write this story about her. A short lifetime of one devoted to assist others, without self-aggrandizement, makes the story of Auntie Yochi’s life an important one to share with others who did not know her; and especially, for her current family members to appreciate, realize, and understand that her genes dwell within them.

* This article is a shortened, revised version of what was written about her in the book about the author’s family, Pillars of a Sansei’s Family, published in 2013.

© 2013 Russell Ukita