The story of Tatsuki John Fujii, a journeyman writer and journalist who was one of the earliest Nisei book authors, offers a rich illustration of the international connections (and complications) of Japanese Americans.

Tatsuki Fujii was born in 1914 in Aichi-ken, Japan, the son of Jiryu (“Jirie”) Fujii and Toshi Fujii. He was still an infant when his family moved to California in 1915. Jiryu Fujii had been a Tendai Buddhist priest in Japan, but he converted to Christianity and became a Methodist minister. The family lived in Merced and later Alameda and Walnut Grove. During these years, two more children, Grace and Henry, were born. The eldest son took the name John, but was also known as “Johnny,” “Piggy” or “Jofu.” Despite his Japanese birth, he considered himself a Nisei.

Like many minister’s sons, Fujii was active in church affairs, and served as president of the Junior Epworth League and the Alameda High School League. Conversely, as his future friend Bill Hosokawa described him, “like many a preacher's son he spent much of his youth violating the ‘thou shalt nots’." For much of his life he would remain a heavy drinker and bon vivant.

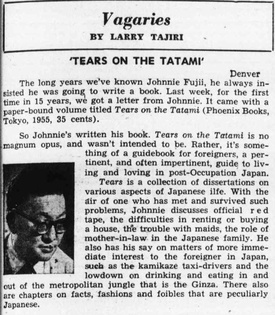

After graduating from Alameda High School, Fujii moved to Los Angeles, where he enrolled, first at Pomona Junior College (later Mt. San Antonio College), then at Pomona College. While at Pomona, Fujii took an interest in journalism. He was engaged as a sports editor of the college daily The Student Life, and worked as assistant to managing editor Joe Shinoda. Fujii soon began writing for the Los Angeles newspapers Rafu Shimpo and Kashu Mainichi. He also performed in a play with the Little Tokyo Players, through which he met journalist Larry Tajiri. Although Tajiri (Fujii’s exact contemporary) was still in his teens, he was already English section editor of Kashu Mainichi. The two became warm friends.

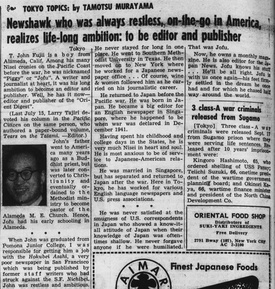

In 1933, Fujii left Pomona and returned to the Bay Area. There he was hired by Tamotsu Murayama as English editor of Hokubei Asahi Daily (a breakaway publication founded by striking staffers from the Nichi Bei Shimbun). In addition to editing, he wrote a column called “Hodge-Podge.” After the Hokubei folded, he was unable to find work.

During the next years, amid the Great Depression, the young Fujii drifted. He relocated to Los Angeles, returned to Pomona, and went to work for the local Nisei press. In February 1934, a daily sports column, “Potpourri,” published under the name T. John Fujii, debuted in Rafu Shimpo. It lasted just 3 months. Fujii left Pomona, and toured Texas and the Southwest. He enrolled at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, but did not remain for long.

He ultimately returned to California, spent some time as an itinerant farm laborer, then took up work as editor of New World Sun, assisting James Omura. (Omura later recalled that Fujii physically attacked him over a trivial difference of opinion, and was fired on the spot by the newspaper’s Japanese editor). Fujii soon moved to writing for Nichi Bei Shimbun, edited by his pal Larry Tajiri. In addition to sports columns and features, he penned a pair of short stories, “Drinks Don’t Mix” and “Scandal Song.” When Tajiri took a leave in early 1936 to tour Japan and East Asia, Fujii briefly took over his “Vagaries” column.

In fall 1936 Fujii moved to New York. He enrolled at Drew University, a Methodist college in New Jersey, and joined the editorial board of a student weekly, Drew Acorn, rising to the rank of Associate editor in 1937. However, he spent much of his time in Manhattan attending shows and visiting nightclubs. He contributed to the West Coast press, and wrote a column, “A Nisei in Manhattan,” which reported on New York events, especially show business.

Fujii left Drew in mid-1938, and returned to Oakland. Having failed at three different colleges, and with job prospects limited by anti-Japanese discrimination and the lack of a diploma, the future may have seemed dim. In August 1938 he published a newspaper piece counseling West Coast Nisei against settling in the Big Apple, and sounded a bitter note. “At the end of the Rainbow, I found a pot not of gold but of excrements. I shook the dust of California only to grovel anew in the muck of New York. But I, I who went, found a land for the rich and the dead, return to the land of the poor but the living.”

At this juncture, fate intervened. In September, Fujii found work in the New York bureau of the Tokyo and Osaka Asahi Shimbun newspaper. His work clearly reached an appreciative audience, as in February 1939 he was recruited by a Japanese consular official in New York to join the staff of the Singapore Herald, a new English-language newspaper to be published in Singapore. Thus, in late March 1939 Fujii crossed the Pacific. Following stops in Tokyo, Shanghai and Saigon, he arrived in Singapore. At the Herald, Fujii served as assistant to editor Bill Hosokawa, a Nisei from Seattle.

In May 1940, Hosokawa moved on to Japanese-occupied Shanghai, and Fujii was named Subeditor (Managing Editor) of the Herald. In keeping with his own background with the Nisei press, he emphasized sports coverage—notably by offering racetrack results on the front page. Otherwise, he reprinted dispatches from the Japanese official news agency Domei and other sources, plus sensational crime stories from the local police blotter.

On December 8, 1941, the Pacific War broke out. The Singapore Herald was closed down. Fujii was rounded up by the British and jailed in Changi Prison in Singapore, then shipped for internment at the Purana Qila fort outside New Delhi, India. There he became the liaison between the Japanese internees and the British authorities. In August 1942, Fujii was one of a group of internees exchanged for British prisoners at Lourenco Marques (today known as Maputo) in Mozambique, and “repatriated” to Japan. He soon returned to Singapore, by then under Japanese military occupation. He worked for Domei, Japan’s official news agency, and for the Information Section of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Even as John Fujii was interned in Asia, his family in the United States was confined at Tanforan and Topaz. In August 1942, diarist Charles Kikuchi wrote in a letter from Tanforan, “John Fujii's family lives next door, and his sister Grace, and brother Henry are here living with their parents. John is supposed to be in camp in Singapore someplace, and his folks are very much concerned about his welfare. They received a letter he wrote around Christmas just recently, so what has happened since then, they do not know.” In 1946, shortly after the end of the war, Henry Fujii enlisted in the U.S. Army.

In 1943, writing under the name “Tatsuki Fujii,” Fujii produced a memoir, Singapore Assignment. The text first appeared serially in three installments over May-June 1943 in the Tokyo-based English-language newspaper Nippon Times [i.e. the long-established Japan Times, which had adopted a more nationalistic name during the war]. Soon after it was released in book form by the Nippon Times Press. (Takabundo Press in Tokyo put out a Japanese-language edition). Though just 122 pages in all, Singapore Assignment is arguably the first full-length book by a West Coast Japanese American to be published by a mainstream press. It is a highly colored account of his experience working with the Singapore Herald in prewar Singapore, and the life he found in the British colony, followed by a discussion of the hardships he and his comrades experienced at the hands of the British authorities during his internment.

In June 1943, Fujii made a trip to Tokyo, which may have been connected with publication of his book. He was en route back to Singapore when his ship was unexpectedly rerouted to the Philippines, due to the threat of American submarines. Fujii spent one month there. His description of Manila, written shortly after the war and later published by historian Grant K Goodman, offers an illuminating account of life under the Japanese occupation. During his stay in Manila, Fujii visited the Santo Tomas internment camp, which would later become notorious for the oppression of the prisoners confined there. In his postwar manuscript, Fujii defended the Japanese governors. “Their internment camp, it appeared to me then, compared very favorably with the treatment I had received from the British at the Purana Qila camp in New Delhi, India.”

In the latter stages of the Japanese occupation of Singapore, Fujii prospered. He found work as a liaison between Japanese civilian officials and the general population. He also got married. Once World War II ended, and Australian troops came to occupy Singapore, Fujii found employment as a liaison between the Australians and the defeated Japanese. At length he decided to settle in Japan with his wife—the couple separated not long after.

Once in Tokyo, Fujii was hired as a correspondent by the International News Service (owned, ironically enough, by anti-Japanese newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst), and his pieces started to appear occasionally in the mainstream U.S. press. As a result, he was well paid by the miserable standards of devastated postwar Japan. He also contributed occasional pieces to the Nisei press. For example, in 1946 he published an article in the newly-founded Nichi Bei Times on jazz bands in Japan. He noted sardonically, “Although there are several good musicians in Japan, most of the present-day bands are run-of-the-mill ‘not good but loud’ types.” He produced a second memoir of his wartime experiences, which he dubbed “Postscript to Surrender,” but it remained unpublished.

Around the end of the Occupation, Fujii was hired as a foreign correspondent by the Associated Press. In October 1952, the second full year of fighting in the Korean War, he was sent by AP to Korea as a war correspondent. His dispatches appeared regularly in the American press.

Historian Monica Kim found the manuscript of a censored article that Fujii wrote after he followed an interrogation team of the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) onto the battlefields: “There is a babel of tongues on this much fought over ridge—a babel of Chinese dialects, Korean, Japanese and one soft Louisiana drawl,” he began his article. (According to legend, Fujii was fired from the AP after he was left alone to staff the office on Christmas Eve. Out of anger at being excluded, he pulled the plug on the Tokyo AP's electronic connections, thereby severing for several hours its connections with the rest of the world). During this same period, he served as editor of the Yomiuri Japan News, an English-language offshoot of Yomiuri Shimbun, and wrote a regular column for it, “The Last Word.” In 1954, he founded and edited Orient Digest, a monthly entertainment magazine.

In 1955, Fujii published another book, Tears on the Tatami, with the Japanese publisher Phoenix Books. In his author’s note Fujii referred to himself archly as “the only illiterate journalist in Japan, John Fujii.” His friend Larry Tajiri described the book as “something of a guidebook for foreigners, a pertinent and often impertinent guide to living in post-Occupation Japan.” Subjects included Japanese mothers-in-law, the problems of buying a house in Japan, and information for foreign visitors such as eating and drinking on the Ginza. The book was accompanied by illustrations by renowned Nisei cartoonist Jack Matsuoka. Two of Fujii’s essays from the book later appeared in Jay Gluck’s 1965 anthology Ukiyo: Stories of the ‘Floating World’ of Postwar Japan.

In later years, Fujii worked for Fairchild Publications (he spent 14 years as Tokyo correspondent for Women’s Wear Daily) and wrote for various British newspapers. He died in Tokyo on 18 August 1996. In a sign of Fujii’s journalistic renown, his memorial service in Tokyo was attended by two former Associated Press bureau chiefs, Tom Dygard and Henry Hartzenbusch, as well as Jack Reynolds, an ex-NBC correspondent.

© 2020 Greg Robinson