The Director of the São Paulo State Sports Bureau who gave permission to fly the Japanese flag at the Pacaembu swimming pool was Mr. Padilha, the same man who had given special permission for the Japanese to use the pool during the war.

The March 28, 1950 edition of the Paulista newspaper carried a comment by Director Padilha, which read, "Never before has a foreign athlete participated in this tournament. We are extremely pleased that we have broken this precedent. You could say that making this exception is an expression of the deep friendship we have for Japan and the Japanese people, and we hope to continue this friendship through sports forever."

Just five years ago, they were treated as enemy nationals, banned from speaking Japanese in public, and were not allowed to gather in groups of more than three people. In an era when many authorities disliked Japanese immigrants, Director Padilha was strangely happy to welcome the swimming team, who surpassed other Brazilian athletes and set new South American records one after another.

Masayuki Mizuno (92, Aichi Prefecture), who was a reporter when the newspaper was first published and accompanied the swimming delegation to Brazil as a reporter for the Japan-Brazil Mainichi Shimbun when the delegation visited, remembers it as if it were yesterday: "Director Padilha was a person who understood the colony, which is why they were given permission to raise the flag. I heard that he was on good terms with a Japanese immigrant who had been running a sports goods store since before the war. Beyond winning or losing, everyone there, including myself, was deeply moved by the raising of the Hinomaru flag."

We should never forget the pro-Japanese Brazilians who appeared at key moments in history. However, even though five years had passed since the end of the war and a swimming team had arrived from Japan, there were still many people in Colonia who could not believe that their country had lost the war.

According to the Paulista Newspaper dated March 28, 1950, the Brazilian Youth Federation, whose headquarters was in Marilia, feared that the arrival of Furuhashi and his party would make the defeat obvious, and "on the day of the tournament, they took a stance of firmly stating that any members of the federation who entered the venue would be expelled. They also planned a speech contest on the day of the competition, and are said to have done everything they could to avoid any opportunities for their members to come into contact with the swimmers, which has caused anger in the local area."

Furthermore, in November of the same year, the police in Malisia arrested 50 members of the "National Vanguard Corps," a fraud group that had deceived the winners into paying for their return home expenses. The leader of the group, Hironori Yamagishi, called himself "Lieutenant Yamagishi of the May 15 Incident," and deceived innocent farmers. Malisia was a place where the aftereffects of the win-lose conflict were particularly strong.

However, the group's visit to Brazil marked a turning point, and little by little, integration within the Japanese community through sports began to progress.

Mizuno recalls, "I accompanied him for over a month, but at that time I wasn't thinking about Okamoto at all. I was only thinking about Fujiyama's Flying Fish group."

He went on to explain the historical background, saying, "At the time, there were no swimmers in the colonia, so there was no one to accept them. Judo player Okouchi quickly took the lead and, together with the tennis players, made a makeshift arrangement to accept them. Since everyone was poor at the time, very few people could afford to send their children to sports clubs with swimming pools." For example, at the time, famous sports clubs in the city of São Paulo were gathering places for the white elite, and very few places accepted Japanese immigrants.

A rebel who resisted Vargas

But who on earth was "Director Padilha"? If you look at the Paulista newspaper from that time, you'll only find him referred to as "Director Padilha." He was such a supporter of Japanese immigrants that he gave special permission to use the Japanese swimming pool even during the war, when Japanese immigrants were looked down upon as enemy nationals, and even gave permission to raise the Japanese flag five years after the end of the war, when the victorious struggle for victory was still lingering. And yet he is a mysterious figure who is only referred to as "Mr. Padilha."

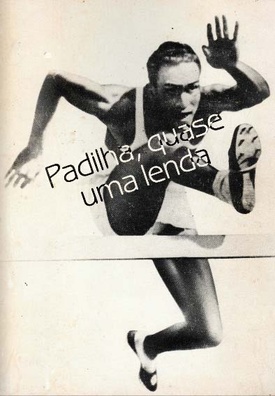

Upon further investigation, a surprising figure emerged: Silvio de Magalhaes Padillha, the most rebellious man in Brazilian sports. He was born in June 1909 in Niteroi, Rio de Janeiro, and died in August 2002 in São Paulo. He graduated from a military school and became a track and field athlete as a career soldier. He was a member of the prewar track and field team (mainly in the 400m hurdles), and participated in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics and the 1936 Berlin Olympics, but did not win any medals.

According to the online edition of the ESPN website's "Olympics B-Side" special feature dated March 24, 2015, the feud between him and President Vargas is deep.

The 1932 Los Angeles Olympics was the worst possible time for the Brazilian team. Vargas led the military in a coup and took power on November 3, 1930. Vargas suspended the constitution, and the people of Sao Paulo rebelled against him, launching a constitutional revolution that lasted from July 9 to October 2, 1932.

The Los Angeles Olympics (July 30th - August 14th, 1932) was held right in the middle of the Constitutional Revolution. Padilha was born in Rio and was sent to the Los Angeles Olympics by the Fluminense club, but the government was so short of funds that it couldn't even cover the team's travel expenses, and instead provided the ship with coffee beans, which the athletes themselves had to sell to cover their participation fees. Many athletes gave up midway, feeling that they couldn't compete under those circumstances.

The following year, in 1933, at the age of 24 and at the peak of his career, Padilha transferred to Club Esperia in the city of São Paulo, and thereafter became a Paulista (a native of the state of São Paulo), which meant he was based in the state of São Paulo, which was at the forefront of the anti-Vargas movement.

His heroic tale from the 1936 Games has become semi-legendary. Although he didn't win a medal, he set a record by becoming the first Brazilian athlete to advance to the finals.

Just before the semi-finals, during warm-up exercises, Hungary's Josef Kovacs, who was said to be the fastest athlete in Europe, reportedly said, "I'm the European champion. I've practically advanced to the finals, but I'll also run against a guy from the land of the monkeys (macacos)."

In the end, Kovacs finished in fourth place, just behind a determined Padilha, and was unable to advance to the finals.

Brazil sent 67 athletes to the Los Angeles Games in 1932 and 94 to the Berlin Games in 1936, but both teams failed to win any medals. This was a big difference from the 77 athletes who participated in the London Games in 1948 and only won one bronze medal, and the 108 athletes who participated in the Helsinki Games in 1952, and only won one gold and two bronze medals.

In other words, the first term of the Vargas administration, which was an unstable administration, was a dark age for Olympic sports.

At that time, Padilha watched sadly from the sidelines as Masanori Yusa participated in the same Olympics and won medal after medal. The Japanese men's swimming team won gold medals in five of the six events at the 1932 Los Angeles Games. Yusa was the central athlete of that era, and was a world-famous star athlete who won two Olympic gold medals and one silver medal, including the Berlin Games.

Due to the misfortune of the times, he was unable to win a medal. However, he entrusted his dream to younger athletes, hoping that they would make it come true. One of them was probably Okamoto.

*This article is reprinted from the Nikkei Shimbun ( August 13th and 16th , 2016).

© 2016 Masayuki Fukasawa, Nikkey Shimbun