Eugene Rostow’s twin articles appeared in late summer 1945. The overall thesis of both pieces was that the indefinite “internment” of West Coast Japanese Americans under prison conditions, and the severe property losses they had sustained, had been a grave injustice - “the worst blow our liberties have sustained in many years.”1 Worse, by upholding the government’s actions in the “Japanese American cases,” the Supreme Court had converted a “wartime folly” into permanent legal doctrine.2

Rostow asserted that in the Supreme Court cases, the government had not offered any proof of military necessity that would justify the army’s wholesale removal and subsequent confinement of West Coast Japanese Americans during 1942, and added that the government could not in fact have provided any such basis, since the actual policy was clearly guided not by military considerations but by West Coast race prejudice.3

Instead of questioning this, the Supreme Court had assumed its own facts, imputing an ethnic presumption of disloyalty onto Japanese Americans by accepting that it was impossible to determine their loyalty on an individual basis. In the process, the Court had given the military a blank check, while ignoring its own precedent in the Civil War-era case Ex Parte Milligan, where the Justices had held that the arrest and imprisonment of civilians cannot be considered a military necessity while civil courts were still in operation.

Rostow underlined the injustice of sentencing one hundred thousand people to indefinite detention “on a record which wouldn’t support a conviction for stealing a dog.” He described the fate of Japanese Americans as a prime example of the evils of racism and warned of its implications for civil rights in general. Writing in the first weeks after the end of World War II in Europe and the revelations of the genocide of European Jews, he proclaimed that even as the American people were weighing the guilt of the German people for the actions of the Gestapo and the SS, they themselves bore the guilt of allowing the Japanese Americans to be confined in what Rostow referred to bluntly as “concentration camps.”4 Rostow concluded by calling on the government to repair the damage it had done to Japanese communities by providing reparations:

“The first is the inescapable obligation of the Federal Government to protect the civil rights of Japanese Americans against organized and unorganized hooliganism… Secondly, generous financial indemnity should be sought, for the Japanese Americans have suffered and will suffer heavy property losses as a consequence of their evacuation. Finally, the basic issues should be presented to the Supreme Court again, in an effort to obtain a reversal of these war-time cases.”5

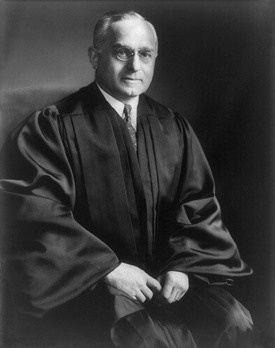

Although Rostow’s two articles today are regarded as seminal pieces of legal scholarship, his critiques were not universally accepted at the time. As mentioned, WRA Director Dillon Myer rejected Rostow’s position as uninformed. Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, to whom Rostow sent a copy of his “dissent” with a request for feedback, responded coyly that as a judge he felt constrained to silence regarding the Court’s decisions, but telegraphed his lack of sympathy for Rostow’s humanitarian arguments. “I only feel free to say that if I had some freedom to write about these Japanese cases I am sure I would not be behind you so far as your Rousseau sentiments of Compassion—or fellow human feeling—go. I can mention Rousseau because he antedates the U.S. Constitution—but in any event you leave me in doubt whether you would enlist under the spiritual banner of Rousseau or the judicial banner of Jefferson!”6

Among the general public, Rostow’s articles likewise elicited a variety of responses. Initially, a number of critics rejected his contention that racism, rather than military necessity, was the main motivation behind official policy. Longtime California journalist Rodney Brink, who had advocated mass confinement of Japanese Americans even before Executive Order 9066, in a January 1942 op-ed piece in the Christian Science Monitor entitled “Internment of Japanese is Demanded”, argued in the Monitor that Rostow’s conclusions were wrong, and that mass confinement was justified under the circumstances. Ignoring the fact that Rostow had spent the war years in active service, Brink dismissed Rostow as an ivory tower academic writing “from his faraway desk at Yale University” who was unaware of the realities of the situation on the ground. Brink’s sentiments reflected widespread public opinion, especially on the West Coast, in the immediate postwar years.

In contrast, the Washington Post formally endorsed Rostow’s arguments. On September 6, 1945, the Post editorial board affirmed that it already had “argued in a number of editorials that the evacuation of the Japanese-Americans from the West Coast, so far from military necessity, was needless and unconstitutional.”7 The editors added that they agreed with Rostow’s finding that the cases need to be presented again, “in an effort to obtain a prompt reversal of this wartime blunder.”8 The Post referred to mass confinement as “a tragedy” that brought “a substantial restriction of the liberties of American citizens because of their racial background.”9

Meanwhile, the celebrated Post columnist Marquis Childs, also echoing Rostow’s findings, advised his readers “to counteract intolerance” on the West Coast in the light of a string of terrorist attacks perpetrated against Japanese American families.10 The Post was one of numerous papers to cite Rostow in order to highlight the injustices of confinement. Rostow’s article received support from smaller syndicated newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, whose editors agreed that the incarceration had indeed “pulled the foundation of justice out from under our law.”11

In the first months following publication of his articles, Rostow moved on to address other subjects, but remained interested in the question of Japanese Americans. In late September 1945, he wrote Washington Post columnist Allen Barth to plead with him to publicize the plight of the inmates held at Tule Lake who had renounced their citizenship under extreme pressure, and who were now threatened with deportation. A year later, the Supreme Court’s decision in Duncan v. Kahanamoku led Rostow to return to the barricades. In the Duncan case the Supreme Court (using Milligan as a precedent) ruled that the use of military tribunals by the wartime martial law government in Hawaii to try civilian cases was unconstitutional. Although the majority opinion in Duncan did not directly touch on Japanese Americans, Justice Frank Murphy’s concurrence scored the government for justifying the existence of the tribunals by anti-Japanese racism.

In a letter to the New York Times dated April 1, 1946, Rostow argued that the Supreme Court’s decision in Duncan was “completely inconsistent” with its record on the Japanese American cases, and he deplored the fact that the Court had passed up such a vital opportunity “to correct itself” from its wartime “mistakes.” He repeated his call for financial reparations for the inmates, “Until the wrong is acknowledged and made right we will have failed to meet the responsibilities of a democratic society—the obligation of equal justice.”12

In the years that followed, however, Rostow only devoted sporadic attention to the issue. In 1959, he was a guest at a Justice Department ceremony marking the conclusion of the evacuation claims process and the awarding of compensation to former camp inmates. In his speech on the occasion, Rostow called the moment a “day of pride for American law.” Rostow likewise was interviewed as part of the 1965 CBS-TV documentary The Nisei: The Pride and the Shame, narrated by Walter Cronkite. While his remarks were brief and largely factual in nature, his presence testified to his continued interest in the question. He remained sufficiently proud of his law review essay on Japanese Americans to reprint it in his 1962 essay collection The Sovereign Prerogative: The Supreme Court and the Quest for Law.

Rostow’s articles remained known among legal scholars and historians of Japanese Americans. In 1981 David Oyama argued in the New York Times that “36 years after Rostow’s words were published,” the establishment of the Commission of Wartime Resettlement and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) had made his dissent a reality. When the Commission published its report in book format in 1983, under the title Personal Justice Denied, it cited Rostow’s 1945 articles as part of the argument for reparations to former inmates.

Ten years after, in the wake of passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Tetsuden Kashima argued in the Washington Post that Rostow’s articles were the first stones in the road of officially recognizing the Japanese American community’s decades of suffering. Recently, Eric Muller offered a tip of the hat to Rostow with both the title and subject of his 2006 article on the Hirabayashi case, “The Japanese American Cases—A Bigger Disaster than we Realized.” Roger Daniels also paid homage to Rostow in his 2013 book The Japanese American Cases: The Rule of Law in Time of War.

Nevertheless, public knowledge of Rostow’s courageous stand gradually faded. Rostow was in part responsible for this, as he experienced a change in political interests and orientation. Even as his brother Walter rose to prominence as a hardline foreign policy advisor during the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations, Eugene Rostow shifted his career from civil rights law towards Cold War foreign policy, and switched his electoral allegiance to the Republican Party.

He was publicly silent during the redress movement, during which time public attention to him focused more on his rise and fall as head of the Reagan Administration’s Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Rostow’s last known public discussion of Japanese Americans came in the form of a critical 1983 book review of Peter Irons’s Justice At War in The Washington Post. While he lauded the book for its “riveting interest and considerable importance,” he accused Irons of distracting readers from the important facts of the wartime cases through “his quest for ‘scandal.’”13

The reasons behind Rostow’s puzzling lack of involvement in the Redress movement - notably his absence from the CWRIC hearing - as well as his criticism of Justice at War, remain unclear. Can it be attributed primarily to his change of political orientation and move towards conservatism, which made him more reluctant to support attacks on past government misconduct and official racism? Since Peter Irons and the lawyers for the 1980s coram nobis cases could be seen as following Rostow in much of their arguments and activism, his complaints about Irons’s sensationalism may indicate a difference in approach between the generations, rather than substance. It also bears noting that in his book, Irons granted Rostow’s pioneering work only a single fleeting mention. Such ungenerosity prompts the question of whether there were also issues of ‘scholarly territoriality’ at play in his dispute with Rostow.

Whatever the cause of his later silence, the legacy of Rostow’s 1945 articles, both for Japanese Americans and the legal community, appears safe. Rostow not only serves as a role model for his arguments, but also for his ability to speak to academics and the American public about an issue so important to civil liberties.

Notes:

1. Rostow, Eugene V., "The Japanese American Cases—A Disaster,” Yale Law Journal, Vol. 54 No. 3 (June, 1945), 490.

2. Ibid, 531.

3. Eugene Rostow, “Our Worst Wartime Mistake,” Harpers, Vol. 191, No. 1144 (September, 1945), 199.

4. Ibid, 201.

5. Ibid, 533.

6. Letter from Felix Frankfurter to Eugene Rostow. August 14, 1945. Rostow Papers.

7. “Wartime Hysteria,”Washington Post, September 6, 1945.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Marquis Childs, “How to Counteract Intolerance,” Washington Post, October 26, 1945.

11. “Our Worst Wartime Mistake,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 20, 1945.

12. Eugene Rostow, “letter to the editor,” New York Times, April 1, 1946.

13. Eugene Rostow, “Shame on the Home Front,” Washington Post, October 23, 1983.

© 2019 Greg Robinson, Jonathan van Harmelen