One pillar of American education is the network of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU). Founded to give free blacks access to higher education in the century following Emancipation, a period when African American students remained largely excluded from mainstream universities, these institutions sprang up all through the South and borderlands. Today, fifty years after the Civil Rights Movement, there are some one hundred HBCUs, both public and private, still in operation in the United States.

Even though their primary mission was to educate African Americans, these universities did not close their doors to non-blacks, either as students or professors. For example, Howard University, a federally-funded institution in Washington DC, admitted numerous white students during its early decades (some of them children of Howard professors). One source states that in 1887 the student body at Howard’s law school was one-third white—its low tuition costs and accessibility made it especially attractive. Meanwhile, Hampton Institute in Virginia admitted large numbers of Native Americans beginning in the late 19th century. HBCUs also attracted a significant international population. Kwame Nkrumah, first president of Ghana, studied at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, while Nnami Azikiwe, first president of Nigeria, was an alumnus of Howard University.

Given all these facts, it is intriguing to inquire about the past relationship of Japanese and Japanese Americans with HBCU—what was the Nikkei presence at these institutions during the Jim Crow era? While the evidence that I have collected so far is fragmentary, it does hint at diverse kinds of contacts.

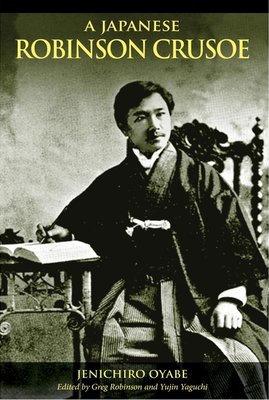

One especially significant early connection was that formed by Jenichiro Oyabe (AKA Koyabe). Oyabe, a Japanese Christian from Hokkaido, who came to the United States in 1888. His goal, as he later recounted in his 1898 memoir A Japanese Robinson Crusoe, was to seek education so that he could uplift the Ainu (Japanese aborigines). He was particularly interested by the opportunity to work with Native American students. After his arrival in the United States, Oyabe was invited by General Samuel Chapman Armstrong, president of Hampton Institute, to enroll there as a special student. Oyabe spent the next two years at Hampton. Curiously, Oyabe does not mention in his memoir the fact that Hampton was an African American school. Not only did he state in his memoir that studying there was a wonderful experience for him, but he appears to have remained attached to the school in later years, following his return to Japan. In 1903, he was interviewed in the Hampton journal The Southern Workman about his missionary efforts with the Ainu in Hokkaido, which included the building of an industrial school on the Hampton model.

In 1890, Oyabe transferred from Hampton to Howard University, where he studied for a degree in theology. At Howard, he became a protégé and companion of president Jeremiah Rankin, who nicknamed him ”Isaiah” and invited him to live in the president’s house with him. Again, Oyabe lauded the school in his memoir, but was silent about his African American classmates. In 1933, Oyabe was invited by Howard President Mordechai Johnson to attend commencement. He declined the invitation but sent a warm reminiscence about his years at the university.

Jenichiro Oyabe was not the only Japanese student at Hampton and Howard at the turn of the century. At Hampton he shared a dormitory room with two other students from Japan, Seijiro Saito and Genta Sakamoto (as well as a Chinese student, Loo Kee Chung.)

Interestingly enough, Saito and his wife would later serve as assistants to Hampton professor Alice Mabel Bacon in her preparation of a revised second edition of her book Japanese Girls and Women (1902). As for Howard, Keisaburo Watanabe, a student from Nagoya, attended the university’s dental school during those years. When Watanabe graduated in 1897, he was offered special congratulations at commencement by President Rankin and by the Dean of dentistry.

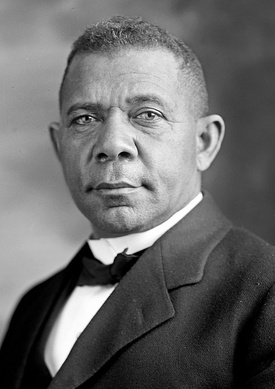

In the first years of the 20th century Booker T. Washington, president of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, became the nation’s most eminent spokesman for African Americans. The “Wizard of Tuskegee” formed important connections with Japan and Japanese. As Brian McLure details in his PhD thesis, “Educating The Globe: Foreign Students and Cultural Exchange at Tuskegee Institute, 1898-1935,” Japanese visitors such as Samuro Kakiuchi and Professor Rishoji of the Imperial University of Tokyo visited Tuskegee on several occasions to study the school’s teaching and farming methods.

According to McClure, the first Japanese student to study at Tuskegee was Iwana Kawahara, who arrived from Tokyo some time in 1906, and graduated in 1908. Kawahara so appreciated his Tuskegee education that he arranged for his sister, Nobu Kawahara, to be admitted to the school. However, her guardian refused to believe that an American college would admit a woman, and ultimately Booker T. Washington was obliged to write to the American Ambassador in Tokyo a letter confirming that she would be welcomed. Once arrived at Tuskegee, she quickly integrated into school activities and made close connections with other students. She graduated in 1911. Perhaps in response to the presence and success of these Japanese students, the Japanese community of Seattle organized to honor Booker T. Washington when he visited the city in 1913, and amassed funds to endow a scholarship for a Tuskegee student.

Fisk University in Nashville was inspired by Tuskegee’s experience to consider attracting Japanese students. However, Fisk president George Augustus Gates felt uneasy about the prospect due to Tennessee state laws that specifically forbade negroes to attend school in company with other races. He was sufficiently concerned that he raised the question of about admitting Asian students to Nashville’s City attorney. In December 1911, Fisk announced that the attorney had issued an opinion that enrolment of any Asian students would be illegal, and the university thereby was obliged to deny admission to a Japanese student. It is not clear how widespread such interpretations of law were. However, by 1916-18, when the magazine The Japanese Student put out a directory of Nikkei students attending universities nationwide, none were listed as attending African American institutions. One source states that Dr. S. Tamanaka attended Southern University in the 1920s, but this is unverified.

What is clear is that in the interwar decades, there were only sporadic contacts between Nikkei and HBCUs. In 1924 Howard University’s baseball team hosted a visiting squad from Meiji University of Tokyo, and prevailed 4-3. The following year Howard’s nine played a game against a group of Japanese former college athletes at Griffith Stadium. Robert Russa Moton, president of Tuskegee, toured Japan in 1927, as did the famed sociologist W.E.B. DuBois, then at Atlanta University, nine years later. In 1940 Kaju Nakamura, a member of the Japanese Parliament and president of the Oriental Culture society, made a lecture tour of African American institutions. He spoke on “Oriental culture” at such institutions as Morgan State University in Baltimore and Dillard University in New Orleans, and tried to recruit African American students to travel to Japan. During these years, the West Coast Nikkei press reprinted reports from Tuskegee on lynchings.

The coming of World War II and the mass removal of West Coast Japanese Americans catalyzed the founding of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC), whose mission was to arrange and secure funding for the transfer of Nisei students to colleges outside the excluded zone. In 1942 Fisk University indicated it would be open to such transfers, and the War Department placed it on the authorized list. However, the executive committee of the NJASRC decided not to authorize admission of Japanese American students to any African American school, for fear of arousing white opposition.

Despite the ban, HBCUs looked for different ways to offer support. In 1943 Jay T. Wright, Dean of LeMoyne College in Memphis, wrote to the WRA to ask its officers to recommend qualified Japanese American candidates for the position of Professor of English. Shortly afterwards, Hampton Institute president R. O’Hara Lanier asked the WRA about the possibility of hiring camp inmates as cooks and dairymen. While no manual laborers seem to have gone to Hampton, Constance Murayama, a graduate of Smith College, was hired by the Institute as professor of English Literature, and served from 1944 to 1946. Howard University admitted a Nisei dental student named Sugioka. Shortly afterwards, Howard invited Nisei activist Bob Iki to give a miniseries of four lectures on the subject of “evacuation and relocation.”

Fisk University became the most active institution in forming connections with Japanese Americans during these years. In 1942, the Japanese-born sociologist Jitsuichi Masuoka moved to Fisk to serve as chauffeur/personal assistant to the famed sociologist Robert Park, who was serving as professor. In early 1943, Masuoka himself was hired as teacher/researcher in the Department of Social Sciences. He became a close collaborator of the distinguished Fisk sociologist Charles S. Johnson. In 1948, Masuoka was promoted to Associate Professor of Sociology. Although Masuoka remained at Fisk for thirty years, his later career there remains somewhat obscure.

Meanwhile, a Nisei student, Dorothy Tada, enrolled in sociology at Fisk. The future YMCA director received her master of arts degree there in 1945. In 1946, JACL president Saburo Kido was invited to attend the famed Fisk University Race Relations institutes. Kido later related that his experience made him aware of very different points of view: “When I spoke about the costs of the evacuation and what the Federal Government was doing, one of the comments made by Negro leaders was that it may not be a bad thing to have a small evacuation if the government would take an interest in the Negro problem to that degree.”

I have been able to find only scattered information on the Nikkei presence at HBCUs in the generation after World War II. In 1955 a Nisei professor, Peter Igarashi, a graduate of Harvard University, was hired as professor of Theology by Virginia Union University. Dr. Osamu Miyamoto graduated Howard’s school of dentistry in 1954, as did Dr. Raymond Shoji Murakami in 1960. Setsuko Hirosawa, a student from Hiroshima, attended Hampton Institute. Barbara Takei, a Japanese American from Detroit, attended Howard University in the late 1960s. Perhaps readers of Discover Nikkei can help fill me in on more of the story!

© 2019 Greg Robinson