I will forever admire my father’s strength and bravery. Despite the incredible challenges he endured during World War II as a young internee in America’s incarceration camps, he lived his life with passion and perseverance.

My father was born in Santa Ana, California on June 6, 1921, to immigrant parents who operated a successful celery farm. When he was five-years-old, he and his parents moved back to Japan to care for his ill grandfather, where he spent the rest of his childhood. Many years later, my grandmother would tell me how smart and studious he was, and that he was a born leader. In 1939, he graduated with honors from the prestigious Kenritsu Yawatahama High School and accepted an internship at the Sumitomo Bank in Los Angeles. Once he moved to Southern California, he met other Kibei-Nisei, those born in the U.S. but raised in Japan. The future looked bright.

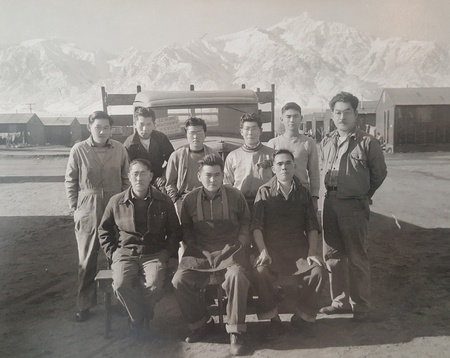

The attacks on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 dramatically changed the lives of the Nikkei, people of Japanese ancestry. Three months later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order No. 9066, authorizing the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese living on the West Coast, two-thirds of whom were American citizens. My father was forcibly sent to the Manzanar Incarceration Camp located just west of Death Valley.

Behind barbed wire in the middle of the desert, his dream of pursuing a banking career was forever shattered. As a twenty-year-old with no family in the States, he must have felt very alone and betrayed.

In 1943, an ‘Application for Leave Clearance’ was given to all adults in the internment camps. Created by the U.S. War Relocation Authority, it included two so-called loyalty questions, Questions 27 and 28, which became a source of major conflict and unrest among the Japanese living in the camps.

Question 27 stated: Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

Question 28 stated: Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, to any other foreign government, power or organization?

Mass confusion and protests ensued.

Did a “Yes” to Question 27 mean the Nisei men would be drafted into the US military while at the same time they were being kept behind barbed wires?

Did a “Yes” to Question 28 infer that the Issei immigrants would become stateless and therefore be separated from their American-born children?

Many, like my father, protested and angrily refused to answer the ambiguous questions or responded “No” to both. Ostracized and labeled as “No-No” boys (later known as the Tule Lake Resisters), they were subsequently sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center in the desolate region of Northern California.

Later in life, in a personal essay titled, “Detention Camp Vagabond,” my father described his experience:

Those judged to be disloyal were to be segregated at Tule Lake camp. Because I had requested to be sent back to Japan, I was already on the blacklist. I went without answering the loyalty questions to Tule Lake. Tule Lake was built to house 10,000 persons but 18,000 were crammed in. Of all the racially discriminatory acts perpetrated by America, I remember this as the worst.

With the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, WWII came to an end in August 1945. The Tule Lake Segregation Center closed the following year. My father was then sent to an incarceration camp in Crystal City, Texas with other Tule Lake Resisters. He described his arrival:

As soon as we assembled, we were given numbers attached to our chest. Not only that, we were also taken to the guardhouse to be searched for contraband. We were forced to disrobe for the inspection. I still remember shouting at the soldier, who was about my age, “What’s the big idea pointing a fixed bayonet at a fellow American?”

In 1947, my father was assigned to work at Seabrook Farms, a frozen foods company based in New Jersey. Later that year, the Department of Justice ordered the release of all Nikkei detainees. My father tasted freedom for the first time in over five years.

I remember asking him why he simply didn’t return to Japan to be with his family. He said that despite the horrific camp years, he wanted to see where his life in America would take him. He soon settled in Pasadena, California where he met my mother and started a family. In his mind, it was too late to pursue a college degree or a banking career. Because of the prejudice toward the Japanese in post-war 1950s, it was difficult to find jobs. So he toiled as a self-employed gardener for the next 40 years. He became a prominent member of the Japanese American community, taking on leadership roles in the Southern California Gardeners Association, the Ehime Prefecture Club, and the Kokuseiryu Shigin (Shigin is a form of singing classical Japanese poems).

My father rarely talked about his incarcerated years. I think it was too painful. Occasionally, I overheard his conversations with his Kibei-Nisei friends. Sometimes, he heard something on the news that would spark his camp experience, and he’d go into an angry rampage. I’m not sure whether he ever forgave America for what was done to the Japanese Americans. But I know he never forgot.

My father passed away in 2016 at the age of 94. He continues to be my inspiration.

It’s interesting to note that in the 75 years since WWII, no person of Japanese ancestry was ever convicted of any acts of espionage or sabotage.

* This is the Nima-kai favorite story from Nikkei Heroes series.

© 2019 Keiko Moriyama