Introduction

On January 30, 1941, a long telegram was sent from Yosuke Matsuoka, a minister of foreign affairs, to Japanese embassy in Washington and forwarded to consulates in the US, including the one in Chicago. The telegram instructed that the ministry had changed the emphasis of its publicity and propaganda work to strengthen intelligence work in the US.

One of the programs Matsuoka mapped out was to “make investigations of all anti-Semitism, communism, movements of Negroes, and labor movements” and to utilize US citizens “of foreign extraction (other than Japanese), aliens (other than Japanese), communists, Negroes, labor union members and anti-Semites in carrying out the investigations.”1

The Tribune Tower in Chicago, which housed the Japanese consulate, had been suspected as a place where “Japanese agents and American Fifth Columnists have gathered by strange coincidence.” Charles J Zeller, Chicago freelance radio commentator and magazine publisher, visited the Japanese consulate frequently and was “reputed to get between $50 and $100 from Masutani, (Japanese Consul), for each piece of Japanese propaganda he puts out over the radio or through the columns of his own Southeast News.”2

On June 11, 1941 Matsuoka sent another telegram to Washington “with reference to propaganda among Negroes as a scheme against the United States” and demanded immediate replies regarding the following points: “training of Negroes as fifth columnists, the way to utilize them in order to begin the movement, the method of contacting the agitators and leaders among the Negroes, as well as both right and left wings”. Mysteriously the telegram was forwarded to New York, New Orleans, San Francisco and Los Angeles, but not Chicago.3

Perhaps in response to this disregard of the Midwest, in December 1942, Tsukao Kawahata wrote a report titled “The American Midwest and Japanese Propaganda” for his office, the Investigation Section Number 4 of the Foreign Ministry of Japan. The report was based on his observations and experiences in Chicago.4 Kawahata had worked as a secretary in the Japanese consulate in Chicago and would repatriate to Japan via the first exchange ship, the SS Gripsholm, in June 1942.

The report described the oppressive environment that African Americans endured and encouraged use of Japanese propaganda to convert them to become pro-Japan in the war effort as follows: “Since the war broke out, most of the antiwar movement among blacks is happening in the Midwest. The most effective tool of propaganda for us, and the most painful problem for the U.S., is the race issue. … There are a lot of restaurants, lodging houses, theaters and others which do not allow blacks to enter. (In this undemocratic situation), it is not impossible to make blacks think that ‘this (the war) is not my business.’ Such a sentiment would destroy the power of the U.S. to execute the war. … It is important to make them understand that only Japanese victory can abolish such undemocratic racial discrimination. One of the blacks arrested on September 21, 1942, Stokely Delmar Hart of the Brotherhood of Liberty for Black People of America said that blacks were the Japanese army in the U.S.… and that he wished that Tojo would win. … Taking into consideration all this evidence of black frustration and anger toward American society, shouldn’t we attach more importance to propaganda toward blacks in the Midwest? Fortunately we have a lot of materials to use for propaganda.”5

Yasuichi Hikida, who repatriated to Japan on the same ship as Kawahata, wrote a similar report titled “Wartime Black Maneuvers” for the foreign ministry of Japan in January 1943. In his report, Hikida suggested using black prisoners of war for Japanese propaganda, training them to do things such as to play music for broadcast.6 Hikida had entered the U.S. through a port in Seattle in April 1920, and had lived in the vicinity of New York City ever since. He lived with a white family as a servant and supported himself as a tour guide and interpreter for Japanese visitors. After the war broke out, he was apprehended in New York in January 1942 and deemed dangerous to the public peace and safety of the United States7 because he had such strong ties with African Americans.

These ties included a 20-year membership with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)8 and the fact that he was called “Prince Hikida” by African Americans in Harlem.9 Historian David L. Lewis described Hikida as an “apologist for Japanese imperialism” as follows: “a pleasant, shadowy Japanese nobleman who courted Afro-American leaders with increasing success. He found considerable sympathy for his cause among certain leaders.” However, Lewis also notes that “there was as much ignorance and suspicion of the Japanese”10 as there were alliances with Japanese people in the African American community.

According to Lewis, “Through Arthur A. Schomburg, curator of the Harlem branch of the Public Library and the Nation’s leading authority on Africans and American-Africans,”11 Hikida was introduced to many African American intellectuals, such as Walter White and James Weldon Johnson, who were both involved in Harlem Renaissance. Around 1933 White praised Hikida and introduced him to Johnson as “my very good friend,” “one of my most esteemed friends,” and “a man who wrote articles to educate the Japanese about the real facts regarding the Negro in the United States.”12 Trusting their generous friendship, Hikida asked White and Johnson to read and comment on his book manuscript on race relations, The Canary Looks at the Crow, and Johnson expressed to White his willingness to write an introduction to Hikida’s book.13

Conversely, Hikida translated Walter White’s novel The Fire in the Flint into Japanese and published it twice in 1935 and 1937 under the pen name of Yonezo Hirayama. Some years later, White expressed his dissatisfaction with Hikida’s translations of his books as follows: “Unwittingly and unwillingly, I was also utilized through the medium of The Fire in the Flint in Japan…. when American indignation over Japan’s invasion of China mounted, a new Japanese edition, with the title changed to Lynching, was brought out. The new edition sold in fantastic numbers, due to a publicity campaign by the Japanese government pointing out that the novel pictured the kind of barbarities which were tolerated and even encouraged in the democracy which had the temerity to criticize Japan for her acts in China. I am glad to say that I never received royalties from either of the Japanese … translations for I wouldn’t have liked that money.”14 In addition to publishing Lynching, that same year, Hikida published his translation of Toussaint L’Ouverture, an 1861 lecture by Wendell Phillips.

Due to his record of accomplishments, such as his publications and his efforts to encourage founder of the NAACP W.E.B. Du Bois, to visit Japan in 1936, Hikida was employed as a translator by the Japanese consulate in New York with diplomatic status in 1938.15 However, he reported to the U.S. government that his employment at the Japanese consulate was only from April to November of 1941.16 In any case, the real purpose of employing Hikida at the Japanese consulate in New York was to utilize him “in propaganda work among the Negroes”17 by trying to “have him foster the organization of Negroes of great ability, thus advancing (Japan’s) own purposes.18 His excellent work in the office secured him a return voyage to Japan and employment in the foreign ministry in Tokyo as “his specialized knowledge will be of value to” Japan.19

Originally, Hikida’s keen interest in African Americans was that of a genuine researcher who “wanted to promote [between] African Americans and Japanese an intelligent understanding of each other.” He dreamed of establishing an Information Research Center of Negro Race and Culture in Tokyo,20 but beginning in October 1940, the U.S. government had become suspicious of his engagement in subversive propaganda activities among African Americans, such as Robert Jordan’s Ethiopian Pacific Movement in New York.21

According to Hikida’s 117 page report, “The War and Blacks: The Black Movement and its Background after Pearl Harbor,” written in October 1942 after he repatriated to Japan, the “black maneuver” by the Japanese government began in 1937, and was carried out through Japanese consulates in the U.S.22 Was the Japanese consulate in Chicago also involved in the black maneuver?

In July 1937, the Japanese army invaded Manchuria. Three months later, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave a speech on “war fears” in Chicago and suggested that “the United States might be compelled to enter alliances with peace loving nations to curb more warlike peoples.”23

Four days later after Roosevelt’s speech in Chicago, on the morning of October 9th, eight or nine African American men and women visited the Japanese Consulate in Chicago and requested an interview with Consul Hideo Masutani. It is unclear whether they knew that the Japanese community in Chicago had already started a fundraising drive to send “relief money” to Japanese soldiers in September 1937. In any event, the group donated 200 dollars in cash and asked the Consulate to send the money to Japanese soldiers in China who were “fighting for world peace and justice.” These men and women were members of an organization based in Detroit and one of the women was married to a Japanese man. They surprised the Japanese by saying that they had been very impressed with Japanese statements to the world and would like to know more about Japan. In response to their interest, the Japanese Consul arranged for Dr. Isamu Tashiro, a Hawaii-born dentist who had a clinic on the South Side at 841 East 63rd St, to go to Detroit on October 17th to give a talk on Japan and China at a pre-arranged meeting.24, 25

Nearly three years later, the FBI office in San Francisco discovered information on this donation to the Consulate in a local Japanese newspaper and reported it to a special agent in Chicago. The FBI identified the group as the Onward Movement of America, which had been established in Detroit to promote racial equality. According to the report, “some of their officials have acquired a “true insight” into the Japanese position through the Japanese consulate in Chicago,” and “they are also said to have obtained much information re the Japanese position through the Japanese Beneficence Society in Chicago,” and “the organization is reported to have recently contributed $100 in Chicago for the families of Japanese soldiers” through the Japanese consulate in Chicago.25

The term “Japanese Beneficence Society” in the report must have meant the Japanese Mutual Aid Society in Chicago. Accordingly, the report seemed to have confirmed to the special agent in Chicago that some African Americans in Detroit had a strong connection with Japanese and the Japanese consulate in Chicago.

The Onward Movement of America in Detroit

The Onward Movement of America was an African American group in Detroit and the successor of an organization called The Society for Development of Our Own. Japanese national Naka Nakane, AKA Satokata Takahashi, founded The Society for Development of Our Own in Detroit in 1933 to organize African Americans against the whites “for the purpose of creating a strong nation within a nation.”26 Nakane claimed that Japan was the leader of the colored races and could “save” African Americans.

Nakane was arrested on December 1, 1933 and deported from the United States to Japan in April 1934 for having entered the U.S. illegally. While waiting for the deportation, in February 1934, Nakane and a black woman, Pearl B. Sherrod, married at the Third Baptist Church in Toledo, Ohio.27 In the same issue of the newspaper reporting their marriage, an article written by Nakane about Development of Our Own under the pen name of S. K.Takahashi. In the article, Takahashi, AKA Nakane, appealed to readers about the necessity for the unification of the colored races.

Three months after deportation, in August 1934, Nakane appeared in Vancouver, Canada “in possession of $2000, and subsequently resided at Vancouver, Windsor and Toronto, Canada, from which points he directed the policies of Development of Our Own through his wife. In September 1938, a marital rift caused Nakane to dismiss his wife from the organization and appoint Cash C. Bates as executive.”28 In any event, we can assume that the black wife of the Japanese man who came to Japanese consulate in Chicago with some other members of the organization in October 1937 must have been Pearl Nakane, and one of the other members must have been Cash C. Bates, a black Baptist minister.

According to an FBI report, “Strife within the Development of Our Own [organization] caused Nakane to illegally re-enter the U.S., through Buffalo, New York in January 1939, using name of Kubo. After coming to Detroit, he reorganized his loyal followers into the ‘Onward Movement of America.’ In June 1939 Nakane was arrested for illegal entry and attempted bribery of a US immigration inspector, was convicted, and was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment and a $4500 fine”29 in September 1939. After that point, Nakane was detained in the Federal Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas and was later transferred to the Federal Medical Center for Federal Prisoners located in Springfield, Missouri. Even after the three year initial sentence was over, his internment continued until 1946.

Nakane was in Canada when his wife, Pearl, Rev. Cash C. Bates, and others visited the Japanese consulate in Chicago in 1937. According to the FBI report, in 1938 Pearl Nakane, “accompanied by six or seven other negroes, came to the office of Dr. Tashiro in Chicago … to make contributions to the Japanese Consul for the Japanese War Chest.”30 Nakane was in a county jail in Detroit after his second arrest when Rev. Bates and the other four African Americans visited the Mutual Aid Society in Chicago on July 6, 1939, met Charles Yamazaki and donated $100 for the benefit of the Japanese soldiers at the Japanese consulate.31 They gave the following reason for this visit to Dr. Tashiro: “a new man had become Japanese Consul and they desired that he acquaint the group with this new consul.”32

Donations to the Japanese consulate from the Onward Movement of America continued even in the summer of 1939, when Nakane left the political scene. For example, when Suejiro Ogawa, who was a Chicago representative of the Japanese Foreign Trade Bureau (a satellite organization of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry of Japan which was housed in the Japanese Consulate at 1500 Tribune Tower) died suddenly in Tokyo in June 1940, “memorial services were held for Suejiro Ogawa in Chicago, five officers of the Negro group in Detroit attended the services and contributed $100 to Ogawa’s family in Japan. The money was sent through the Japanese consulate in Chicago.”33

Notes:

1. The “Magic” Background of Pearl Harbor, Volume I, page A-76.

2. Michael Sayers, “Japan’s Undercover Drive in America,” Friday, February 14, 1941, page 5.

3. The “Magic” Background of Pearl Harbor, Volume II Appendix, page A-179.

4. Protocol No. 2, dated December 1942, investigation bureau No. 4, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, cho4_25.

5. ibid.

6. Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, A-7-0-0-9_10.

7. Warrant by Francis Biddle, January 14, 1942, Hikida file, RG 60 WWII Alien Enemy Internment Case Files, 1941-1954, Case File 146-13-2-51-844, Box 410, FBI Case File 100-704.

8. Reginald Kearney, African American Views of the Japanese: Solidary or Sedition, page 83.

9. David L. Lewis, When Harlem Was in Vogue, page 137.

10. Ibid, page 302.

11. Amsterdam New York Star News, January 3, 1942.

12. Reginald Kearney, African American Views of the Japanese: Solidary or Sedition, page 83.

13. Hikida’s letter to Johnson, dated October 11, 1935.

14. Walter White, A Man Called White, page 69.

15. Idei, Kokujin ni mottomo aisare, FBI ni mottomo osorerareta nihon-jin (A Japanese who was most loved by blacks and feared by FBI), page 240.

16. Hikida file, RG 60 WWII Alien Enemy Internment Case Files, 1941-1954, Case File 146-13-2-51-844, Box 410, FBI Case File 100-704.

17. Telegram from Washington to Tokyo, dated December 5, 1941, The “Magic” Background of Pearl Harbor, Volume IV Appendix, page A-223.

18. Telegram from Ambassador Nomura to Tokyo, dated July 4, 1941, The “Magic” Background of Pearl Harbor, Volume II Appendix, page A-180.

19. Telegram from Washington to Tokyo, dated December 5, 1941, The “Magic” Background of Pearl Harbor, Volume IV Appendix, page A-223.

20. Reginald Kearney, African American Views of the Japanese: Solidary or Sedition, page 84.

21. Idei, page 239.

22. Report, investigation bureau No 6, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 1-4-6-0-1_3. Idei, page 208.

23. Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1937.

24. Nichibei Jiho, October 16, 1937.

25. FBI memorandum from special agent in San Francisco to special agent in Chicago, August 7, 1940, FBI file # 65-562-53X.

26. Memorandum for the director, Bureau of Prisons, from John E Hoover, dated February 28, 1941, FBI file#65-562-61.

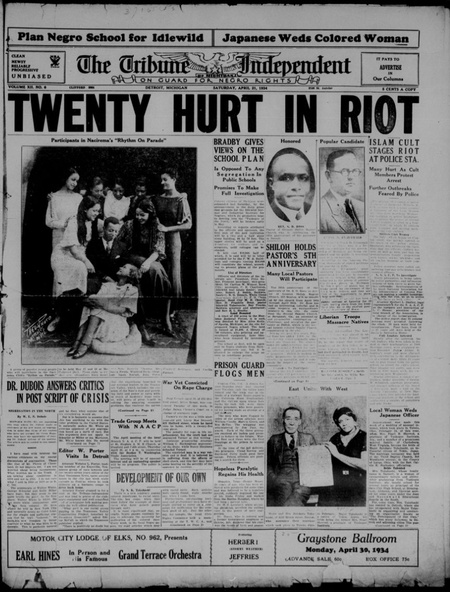

27. Tribune Independent, April 21, 1934.

28. FBI Report, dated March 29, 1940, Detroit File No 62-709.

29. Ibid.

30. FBI Chicago report, dated April 11, 1944.

31. Executive Secretary’s notes, 1935-1941, Japanese Mutual Aid Society of Chicago, page 230. Day, "Suspicious Points of Contact in Pre-War Chicago: The Japanese Mutual Aid Society and Charles Yasuma Yamazaki," Discover Nikkei.

32. FBI Chicago report, dated April 11, 1944.

33. Frank Masuto Kono, WW II Alien Enemy Internment Case Files, 1941-1954, General Records of the Department of Justice, RG 60 Box 272, Case File # 100-10053.

© 2019 Takako Day