Here’s an intriguing idea about how to think about your Japanese Canadian identity: What if it were a cake recipe what would go into it and how would you construct or, perhaps, more aptly, deconstruct, it?

De/constructing my own Japanese Canadian identity over the years, I’ve learned that the foundation of the Japanese part of my cultural shaping would include the food, my awkward way of interacting with others (especially in Japanese), Buddhism, aikido, how history has twisted and bent my identity, the novels of Yukio Mishima, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki, Kenzaburo Oe, and writer Naoya Shiga’s A Dark Night’s Passage in particular, the movies of Akira Kurasawa and even those campy Godzilla movies from the 70s. Then add the layers of living in Japan for nine years.

My Canadianness would be a mishmash of history that was slow to seep into my consciousness. For example, when my high school history teacher/basketball coach Jim Costagan had the guts to introduce me to institutionalized racism against Japanese Canadians (JC); reading Joy Kogawa’s novel, Obasan, definitely; and the New Canadian newspaper that had a trickle down effect; Nisei like Jesse Nishihata (Montreal), Pauli Inose (New Denver), George Doi (Langley), Tak Matsuba (Osaka), Lloyd Kumagai (Tokyo via Lemon Creek), and Grace Eiko Thomson (Vancouver) whose strength of character and passion for being who they are a well of inspiration that I often return to. There are a whole slew of Japanese Americans who made their impact on me as well, —most notably Tom Okada.

There is a lot of back and forth that involves cross cultural stuff, such as my trans-Pacific flights between Japan and Canada as well as personal trips within Canada. On long walks with my dog, Yuki, I often amuse myself by engaging in games involving the deconstruction of myself. I’ve given up counting the strands that make up my identity. I gave up when I faced the question of what was I before I was born? I get hints when I look at black and white pictures of my own wide-eyed parents as helpless kids caught up in the riptide of Canadian dysfunction and racism. I thought that it was understood by all of us that you don’t treat anybody, even JC kids, that way….

Our families were shamed into maintaining an eerie silence about themselves through the generations. So, the value of the Canadian Nikkei Artist series is that these are often little known, even reclusive members of our JC community, who have so much to say about being Japanese Canadian. We need to listen to the voices of our artists. I would like us to rip off that terrible muzzle that has been in place for so long and give those who still a voice and a forum to express it. The meat grinder of racism and cultural genocide have not muzzled us completely yet. Younger generations still have a chance to find their voice as Japanese Canadians.

On experiencing Onoway, Alberta’s Marjene Matsunaga Turnbull’s claywork Continuum: A Japanese-Canadian History Cake, featured in the Royal Ontario Museum’s (Toronto) exhibition Being Japanese Canadian: Reflections on A Broken World, my consciousness was opened a crack: what a simple but profound way to see us as Japanese Canadian individuals and community. The sculpture is formed in the shape of a three layer cake, with complex layers of historical and cultural references visually gracing the “cake’s” surfaces.

* * * * *

The layers on Marjene Matsunaga Turnbull’s Continuum: A Japanese-Canadian History Cake were inspired by her own Japanese Canadianness and I asked her to share her thoughts on her art and what being Japanese Canadian means to her:

I think the major barrier to me as a sculptor was how I felt about myself. Here I was, a quiet unassuming person making pieces that were loud with social and political statements. At the time, this was the way I could express my feelings of hurt and anger at the injustice done to my grandparents, parents, relatives and me. It didn’t bother me that some sculptures were not “Japanese” looking e.g., subtle with quiet beauty. My pieces became loud and often garish in colour and message. I could overcome my shyness with my art.

Since I was born in 1947, I did not experience what my parents and grandparents did, living in Mission, BC. My grandparents and their children, along with two married daughters and their young families, were included in the second contingent to arrive in Southern Alberta in April 1942. My father, Todomu Matsunaga, and his brother, Kiyoshige, had moved to interior British Columbia and were self-supporting in Vernon, working in apple orchards. Todomu travelled to Picture Butte (Alberta) to marry my mother Kimiko in 1944. She had to get permission from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and British Columbia Security Commission to travel to Vernon a month later. Todomu and Kimiko lived and worked in Vernon and had two children. At the request of Kimiko’s father to be closer to the rest of the family, they moved to the sugar beet farm near Nobleford when I was six months old. They then were able to move to Lethbridge (Alberta) where my older sister Kathy and I were raised. My father, who was going to be a teacher in Japan, worked all his life as a menial labourer. My mom was a seamstress working at home. Both my sister and I were able to go to university and became a pharmacist and teacher.

As a child, I felt panic when I heard the curfew sirens in the evenings. Some children at playschool threw stones at me and name-calling was frequent in the neighbourhood. I experienced terror when my grandfather was stopped for driving too slowly and I thought we were going to be taken to jail. Even as an adult, I felt terrible anxiety when I was followed and stopped by the RCMP. I was given a citation for good driving!

When I married Brian and had children, Adam, Miya, and Michael, I needed to teach them of my family’s past. ([I also have] five grandchildren, Jacob, Azalea, Beatrix, Elizabeth, and Grant.) The questions asked of Mom and Dad were sporadically answered and never completely understood. I recall seeing a movie that I think was Farewell to Manzanar and it left me in tears. After reading books by Shizue Takashima (A Child In a Prison Camp), Joy Kogawa (Obasan), Ken Adachi (The Enemy That Never Was), Ann Sunahara (The Politics of Racism) and Michi Weglyn, for example, things started to make sense. Other publications came out and I learned more about the Japanese Canadian internment and uprooting.

I needed to know how my family’s history fit within the general Japanese Canadian history. In 1981, I asked extended family members to write about their memories of growing up. With research and especially with my mother’s help, I wrote the story of Ichirohe and Kin Hisaoka. After the book, Hisaoka Family Memoirs, was finished in 1991, it was a natural extension in my clay work to make clay sculptures.

I didn’t have any art courses in school. The first time I handled clay and experienced different media was when I was in university doing the method course on art. I loved it! I had started out doing education courses then realizing that I didn’t want to continue, switched to get my general arts degree with a lot of sociology courses. I was one course short, and, worried about a job, finished my education degree.

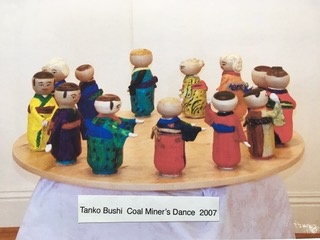

As for my pottery, I had a few classes with Noboru Kubo at the Department of Extension at the U.of A. and I used a lot of Japanese techniques in making my pots. My father was an excellent calligrapher, with bold strokes for kanji. I tried to make my brushwork for leaves and grass look elegant. The kokeshi is my signature piece and I used it in most of my sculptures. The individual kokeshi I had made and sold were each unique in facial expression, design and color of stylized kimono.

Being a potter and sculptor has definitely impacted me as a JC. I have a little more confidence about myself, while living in some isolation, on a farm near a small town. My thoughts and feelings about being a visible minority have been expressed and I feel that I’ve come to terms being who I am. I no longer have the negative feelings of being JC and have long lost the childish wish to have blonde curly hair.

This was in the ‘70s and ‘80s, Brian went into farming with his father on the family farm just outside of Onoway, and we had three children and built our own house. I did a lot of breadmaking, gardening, pickling and freezing produce. I had chickens, ducks, and pigs. We grew wheat, barley, oats and canola on 1200 acres and raised cattle. I helped with calving and drove huge tractors.

When my youngest child was about two years old, I started with a drawing class at the University of Alberta (U of A), then pottery classes with the Parkland Potters Guild in Stony Plain with more advanced classes at the Dept. of Extension at the U of A. I’ve had some painting classes just in the community. So really, I’ve had no special training in arts. I just enjoy myself creatively.

I made functional pottery and sculptural forms for almost 30 years. My sculptures are reflections of historical, political and social aspects of my Nisei-Sansei identity. I am honoured to have the ROM (Royal Ontario Museum) purchase my sculpture Continuum: A Japanese-Canadian History Cake for their permanent collection.

So, what does being Japanese Canadian mean to me?

Being a Japanese Canadian person is a person who is not a Caucasian Canadian and not a person born in Japan. A Japanese Canadian is one who grew up in the distinct culture of “Japanese Canadian-ness” with the history of the attempted “ethnic cleansing”. It is a person who has great admiration, gratitude, and pride for the NAJC who worked with such dignity and strength in attaining Redress. As a Japanese Canadian, I am a visible minority living on a farm outside of a small town and am sometimes lonely for a community of Japanese Canadians. I am ever mindful of racism directed towards my children and grandchildren.

Today?

I have no plans for any pottery or sculpture these days. When I submitted photos of Slave Labor, Dance of Atomic Shadows, Yellow Peril/Yellow Fever along with Continuum and Jerry, Army Cadet to Heather, she thought there might be something else for them somewhere, some time. It would be interesting but I’m not holding my breath about it.

Nowadays, we are still living on a farm, which is about an hour’s drive northwest of Edmonton. Since we are both retired, we rent out the farmland. “We had restored the barn into a house with our oldest son. Brian continues to restore antique tractors. I retired from pottery about seven years ago and my studio became his woodworking shop. Our two sons came back to the farm from city life, and they and their families live next door to us. I enjoy babysitting and getting to know the grandchildren. That’s it!

© 2019 Norm Ibuki