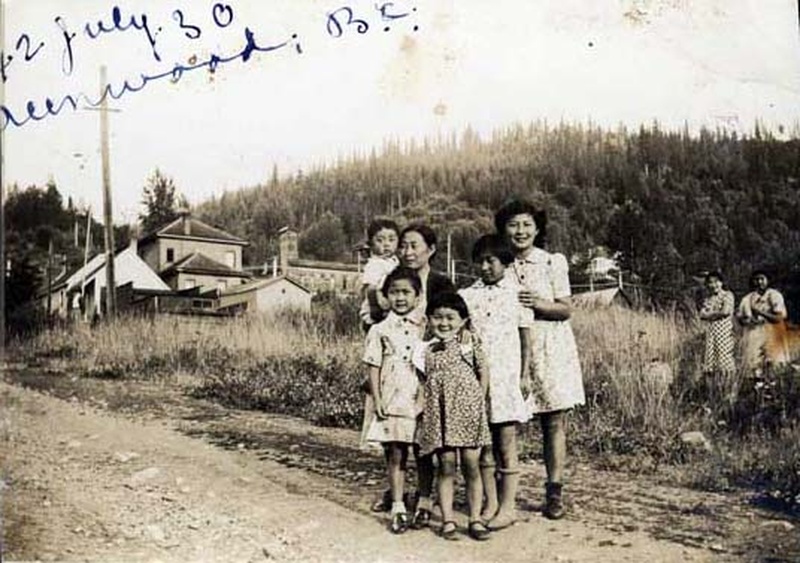

While the family was in camp, the Canadian government was doing everything in its power to rid the Japanese Canadians from British Columbia. They passed PC 469 under the War Measures Act, which gave them the right to dispose of the Japanese Canadians’ property without consent.

The family farm on Salt Spring was sold for pennies on the dollar. My grandparents were shocked. Salt Spring Islanders had promised to keep their property safe until their return. My Bachan remembered one man who put his arm around her and said, “Don’t worry Kimi, not one chopstick will be moved.” A year later, these same people were benefiting from the forced sales of the family’s property. After all the transactions were deducted, the family received $500 for years and years of hard work and sacrifice. Their household belongings were stolen, and now the home and land were gone. The money was put into a bank account and frozen; then doled out for them to live on throughout their incarceration. There were times when my Bachan asked for more money to buy winter clothes and baby things, but was always told a resounding NO. The government wanted the Japanese Canadians to live on their own money as long as possible.

In 1944, the Canadian government gave an ultimatum to the Japanese—either be exiled to war-torn and starving Japan or move east of the Rockies. Their slogan was, “No Japs West of the Rockies!”

So once again, the family moved inland to Magrath, Alberta, hoping to one day return to Salt Spring and to farm once again. My mother worked as a clerk in a grocery store and her earnings were crucial to the family’s survival. The family reluctantly took over a failing restaurant that was originally started by my great-grandfather Okano, but was now in debt. My grandparents bought the restaurant to pay off the debt and make some money, with Bachan as the cook; working two shifts a day and Geechan as the baker of bread, buns, and pies. The older children all pitched in and worked there too. It took six years to pay it off and move back to Salt Spring.

In 1949, four years after the war had ended, the restrictions were lifted and now the family could move back. They returned to Salt Spring Island in 1954 after working and saving $9,000 to buy the house and five acres. They were the only ones to ever return and start all over on the island.

By 1952, Alice and Ted (my parents) were married and living in Chicago. Both were working and my mom was sending money home to her family to help pay bills until they could make money from farming. For the first year the Murakamis were back on the island, they spent their time clearing the land. My mom told me that Ted (my Dad) considered Geechan to be his father and my mom and dad got a bank loan to help the Murakami family. My parents paid off the loan after my mom and dad moved to California and was able to secure higher paying jobs.

Coming back to the island was not easy either. Bachan and Geechan were not welcomed at all. Groups protested and Revenue Canada (IRS) came to challenge where the money came from to buy the farm. Even the senior of the Anglican Christian Church, where all of the children had been baptized and that the family had financially supported, came and told my Bachan and Geechan that they were not welcome and they were evil people.

But through hard work, the family cleared the unwanted land that they had bought, burning and clearing large tree stumps, digging out boulders and digging new drainage ditches and wells. In time, the land became a remarkable market garden with crops of berries, asparagus, and other fruits & vegetables. A gorgeous flower garden decorated the whole front of the farm. For as long as my grandparents had the business, many Salt Spring Island citizens and regular summer visitors supported them by enthusiastically buying their produce and berries.

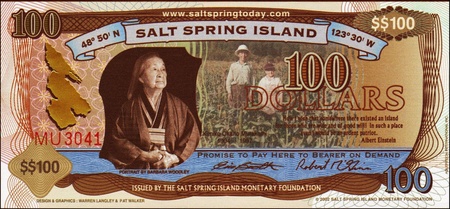

My Bachan left behind a lasting legacy of perseverance and she ultimately triumphed in the face of almost indescribable adversity. In her lifetime, she claimed an extraordinary number of firsts for Japanese Canadians: She was the first Japanese Canadian woman born in Steveston, BC 1904; the first woman to drive a car on Salt Spring Island; the first woman to have her image printed on a North American banknote ($100 bill); and her portrait (as part of the Women of Canada) hangs permanently in the National Archives in Ottawa which is like the Smithsonian Portrait Gallery, in Washington DC.

Among her friends and admirers, she counted former BC Premier Bennett, and many other celebrities who came each summer to visit and buy some fruits and vegetables. She also has documentaries on her life created by Canadian Broadcasting Company.

My Geechan died in March 1988 and my Bachan died in July 1997. They were a powerful and resilient team, my role model and heroes. They taught our family to never act as victims and to always show a proud face to the world… never a face of defeat. They taught and showed us how to be generous and compassionate towards others. Throughout their lives, they were truly honorable and loyal citizens of Salt Spring Island, BC and Canada. With dignity and courage, they brought the family through some terrible, terrible times in their journey through life and ensured that the family did prevail.

Thank you all for letting me share my family’s history and stories of the Japanese Canadian internment history.

© 2019 Gerald Tanaka