Two brothers named Totaro and Kazuma Nishikawa formed part of an important wave of Japanese fishermen who settled in Ensenada in the early 1930s. Twenty years before, however, the first Japanese fishermen had already arrived in Baja California, when the Porfirio Díaz administration granted Aurelio Sandoval a fishing permit that Masaharu Kondo, an expert in fishing technology, would subsequently approve upon realizing the fruitfulness of the waters of Baja California.

The fishing industry in the peninsula would enjoy a boom from 1930 until the beginning of World War II, thanks to the permits and investments that various business entities undertook to produce and pack a large variety of seafood products. One of these businessmen was Shin Shibata, who based his company in Los Angeles, California. Two others were Mexican: Luis Salazar, who founded the Compañía Industrial de Ensenada, and General Abelardo Rodríguez, a remarkable businessman and politician who served as interim president of Mexico from 1932 to 1934.

General Rodríguez, starting in the period before his tenure as president, took advantage of his political capital to obtain wealth and do business of all kinds. In terms of fishing, he acquired the Bahía Tortugas Packing Company after his own facilities mysteriously burned to the ground. This company was established by Masaharu Kondo in Bahía Tortugas to receive products that Japanese fishermen brought in abundance.

The Japanese fishermen formed a crucial part of the expansion due to the training and experience upon which the project relied. Moreover, among these fishermen were divers who were specialized in methods of harvesting abalone that were unknown to their Mexican counterparts at the time. For these reasons, large diasporic communities were established not only in Mexico, but also in the port cities of Los Angeles and San Diego in the United States, as well as in Canada.

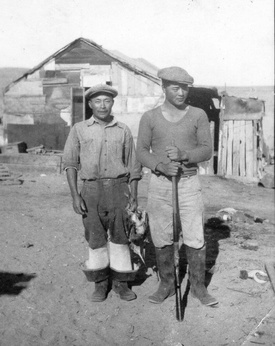

Totaro and Kazuma belonged to this group of divers who joined Shibata in Japan. The brothers were raised in the fishing town of Sagara, to the south of Shizuoka prefecture. Both learned the profession from their father and grandfather. Totaro was born in 1901, the firstborn of the Nishikawa family, which apart from fishing was also involved in rice and tea cultivation as well as sea salt production. Kazuma was the youngest child in the Nishikawa family, having been born in 1918, and there was an age gap of 17 years between the two, with six brothers who were born in the interim.

Totaro saw the opportunity to improve the financial situation of his family in Shibata’;s offer of work. However, Totaro initially considered his stay in Mexico to be temporary, as in 1922 he started a family with his wife Mura with whom he had three children: Masayuki, Katsuko, and Shosaku. In 1931, Totaro joined Shin Shibata & Company, the headquarters of which was located in Wilmington, California opposite Terminal Island, an artificially constructed land mass in Los Angeles where hundreds of fishermen of diverse nationalities lived.

The Shibata company was tied to the interests of General Abelardo Rodríguez. General Rodríguez knew very well to make the most of Shibata’s business and the expertise of its Japanese divers, and his company took it upon itself to purchase the abalone collected in large quantities to later export and process in the United States as well as in Asian countries.

The fishing activity of Japanese immigrants was divided into two large groups. There were the fishermen who fished tuna, sardines, and bonito, among other species, and the group of divers that harvested abalone. The fishing seasons differed by group, as the abalone harvesting season ran as long as April to December.1

Totaro arrived in the United States by boat in early 1931, and later entered Mexico through Tijuana in March of that same year. Initially, the Shibata company’s divers and fishermen did not have a permanent residence in the United States or Mexico. They lived for a few months in Shibata’s Long Beach offices and spent the rest of the year in fishing camps that they established on the Baja California coasts between Ensenada and Bahía Magdalena, including Cedros Island and other areas. 2

After five years in Mexico, Totaro returned to Japan in 1936 to see his wife and three children. His stay in Japan would only be temporary, as he returned to Ensenada that same year. During his visit, Totaro invited his younger brother, who had already turned 18, to join the group of divers. He realized that there lay great opportunity for Kazuma in Shibata’s company due to the growing abalone industry. Totaro was so optimistic about his future in Mexico that planned to apply for naturalization as a citizen, which he ultimately did at the end of the following year.

Kazuma’s chance came in the spring of 1937. Against the will of his parents, he traveled to Mexico through the yobiyose system, which allowed Japanese people to enter the country upon proof that a friend or relative would cover the visitor’s living expenses. Kazuma and Nadao Sugimoto, a 20-year-old from Shizuoka, entered Tijuana in May and immediately joined the team of expert divers that included Soichi Sakurai, Iwashi Suzuki, and Ginzo Nagai.

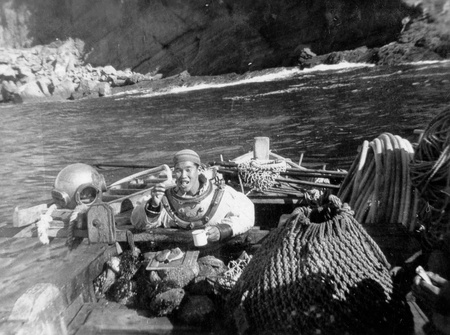

The divers used three types of boats in their work. Among these was the pontoon, a sailing yacht where the seven or eight crew members ate and slept on trips on the high seas that could last up to a month. Another boat was the panga, where the abalone was stored and cleaned in enormous water tanks. The third type of boat was another wooden panga, which the group of divers used to harvest the abalone.

Each team of divers consisted of four people. One crewmember would dive for two or three hours to collect the mollusk; he would peel the shells off the rocks and place them in a mesh bag where he would store them before surfacing. Another held the lifeline that the diver pulled to signal that he needed to surface. The jabero was charged with raising the jabas, or mesh bags, which the diver filled with product. The jabero also shucked the abalone. Finally, the bombero pumped oxygen to the diver with a long hose throughout the day. At the end of the season, the abalone was sent to the company Pesquera del Pacífico, owned by General Rodriguez, in El Sauzal where it was cleaned and cooked before being packed for export.

By 1939, business was going smoothly for the Nishikawas. Kazuma, though he did not speak Spanish, adapted very quickly to his new life. With the help of a dictionary, he gradually grew able to interact with the community of Ensenada, who knew him as Jorge. Kazume was driven by his intense work and his compensation in U.S. dollars, which allowed him to live comfortably in Mexico. His ability to harvest abalone broke a record, capturing 1,367 kilograms of mollusk in a single day.

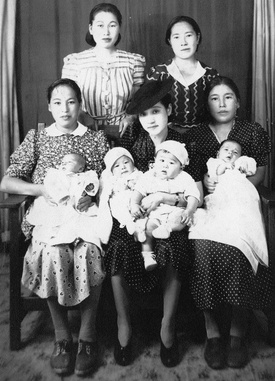

On the other hand, Totaro’s wife Mura arrived in Mexico in April 1939. The distance between the two had been difficult, so the couple concluded that she should come to Ensenada. Mura traveled aboard the Kamakura Maru from Yokohama harbor, without her three children. She accompanied several immigrants who were also on their way to Ensenada, including Michi Saito, a fisherman who had also applied for Mexican nationality, and his wife Ai Saito.

By the time Mura arrived in Mexico, Totaro had already chosen Ensenada as his residence for off-seasons. The house, located on Miramar Avenue, was located in a neighborhood where man fishermen lived. The Nishikawas had decided to leave their three children under the care of their paternal grandparents while they sought a permanent home. Although Totaro was about to receive Mexican nationality, he had also saved a significant amount of money in Japanese currency in a bank in Los Angeles, at his disposal in case of his return to Japan. Additionally, Mura became pregnant in early 1940, bringing enormous joy to the couple. In September, his first Mexican daughter, Sachiko, was born. In November 1941 his second son Yukio was born, also in Mexico.

Although the Nishikawas were very satisfied with their achievements, they were troubled by the situation of their three older children who lived with their grandparents in Shizuoka. Not only that, the winds of war in the Pacific were looming.

Notes

1. Interview with Kazuma Nishikawa by Sergio Hernández Galindo, December 2010, Guadalajara, Jalisco.

2. Interview with Kazuma Nishikawa by Kiyoko Nishikawa Aceves, May 1997, San Diego, California.

@ 2019 Sergio Hernández Galindo, Kiyoko Nishikawa Aceves